yeovil at War

henry hilborne

Veteran of India and the Boer War killed in Mesopotamia

Henry Hilborne was born late in the year 1878 in Yeovil. He was the son and youngest child of farm labourer Mark Hilborne (1827-1889) and glover Sarah née Denty (1840-1919). Mark and Sarah had ten children; Sarah Ann (1859-1928), Martha (b 1861), William (1864-1882), George (b 1866), Frank (1868-1926), Walter (b 1871), Edward (1872-1922), Emma Jane (1874-1960), Mary Elizabeth (b 1876) and Henry (1878-1916).

In the 1881 census 54-year old Mark and 45-year old Sarah were living in a remote cottage in Combe Street Lane with their children. The eldest three sons still living at home, George, Frank and Walter, were all labourers. Henry's father died in 1889 when Henry was just 11 and in the 1891 census Henry and his his widowed mother, now working as a charwoman, were listed as visitors in Paddington, London.

Around

1893 Henry

enlisted as a

boy soldier at

Dorchester, Dorset,

giving his

residence as

Yeovil.

He was a

Private (Service

No 5363) in the

2nd Battalion,

Dorsetshire

Regiment.

Around

1893 Henry

enlisted as a

boy soldier at

Dorchester, Dorset,

giving his

residence as

Yeovil.

He was a

Private (Service

No 5363) in the

2nd Battalion,

Dorsetshire

Regiment.

Although its

roots go back to

1702 the

Dorsetshire

Regiment was

officially

formed in 1881

from the

amalgamation of

the 39th and

54th Regiments

of Foot. The 2nd

Battalion was on

the move in the

1890s, firstly

to Ireland and

then to South

Africa for the

Boer War

(1899-1902),

where it fought

at Elandslaagte

(1899) and took

part in the

Relief of

Ladysmith

(1899-1900).

The Battle of

Elandslaagte was

one of the few

clear-cut

tactical

victories won by

the British

during the

Second Boer War.

However, the

British force

retreated

afterwards,

throwing away

their advantage.

While three

batteries of

British field

guns bombarded

the Boer

position, and

the British

advanced

frontally in

open order and

moved around the

Boers' left

flank. The sky

had steadily

been growing

dark with

thunderclouds,

and as the

British made

their assault,

the storm burst.

In the poor

visibility and

pouring rain,

the British

infantry had to

face a barbed

wire farm fence,

in which several

men were

entangled and

shot.

Nevertheless,

they cut the

wire or broke it

down, and

occupied the

main part of the

Boer position.

The way was now

clear for the

British

detachment at

Dundee to fall

back on the main

British force,

but Sir George

White feared

that 10,000

Boers from the

Orange Free

State were about

to attack

Ladysmith, and

ordered the

force at

Elandslaagte to

fall back there.

The British were

tired and many

officers had

been killed, and

the retreat

became a

disorderly

scramble. The

Boer forces

re-occupied

Elandslaagte two

days later.

After the Battle of Ladysmith on 28 October 1899, the Boers succeeding in entrapping some 8,000 British regulars in Ladysmith. By the middle of December, British and Empire troops were pouring into Natal. After much fighting, including the Battle of Spion Kop (20-24 February 1900), the Battle of Vaal Kranz (5-7 February 1900) and the Battle of Tugula Heights (14-27 February) on 28 February the Boer commanders ordered their troops to withdraw to the Biggarsberg, some 45 km to the north of Ladysmith. There was little organisation in the withdrawal, but the British forces were instructed not go in pursuit. The British forces entered Ladysmith on the afternoon of 1 March 1900.

The 2nd Battalion moved back to India in 1906 and was in Poona, India, when the First World War broke out. The Battalion was shipped to Mesopotamia, landing at Al Faw in the Persian Gulf on 6 November 1914.

One of the primary reasons for initiating the campaign in Mesopotamia was to defend the oil refinery at Abadan at the mouth of the Shatt al-Arab. The British Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, led by General Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend, marched north from Basra in September 1915 in what became known as the Mesopotamian Campaign. They reached Al-kut on September 26, where after three days of fighting they drove the Ottoman forces from the town. After a halt of nearly 9 months, Townshend then headed up river to Ctesiphon. Then, after a year of a string of defeats, the Ottoman forces were able to halt the British advance in two days of hard fighting at Ctesiphon.

Townshend ordered a night march in the closing hours of 21 November 1915, with the aim of attacking at dawn on 22 November. The attack happened on schedule but due to poor ground conditions on the west bank the British ended up attacking the much stronger east bank positions. By the end of the day the British had captured the first line of trenches, but sustained heavy casualties. The Ottoman forces had also taken heavy casualties but held their position. On the second day, Townshend again attempted to break through, with a supporting flank attack. The Ottoman forces again stopped it. They then counter-attacked the British positions with all available forces. The fight was hard, but the British line held. Both armies had taken heavy casualties and all troops had endured two days of intense combat and were exhausted. On the third day, 24 November, both generals ordered a withdrawal.

Following the battle at Ctesiphon, the British forces withdrew back to Kut al-Amara. On 7 December 1915, the Turks arrived at Kut and began a siege. The British cavalry succeeded in breaking out, but Townshend and the bulk of the force remained besieged. Many attempts were made to relieve Townshend's forces, but all were defeated. The 2nd Battalion was trapped in the Siege and in late December 1915 they were forced to surrender, after 100 days, and were captured by the Turks. Some 23,000 British and Indian soldiers died in the attempts to retake Kut, probably the worst loss of life for the British away from the European theater.

The Battalion then suffered cruelly in the 'death march' to prisoner of war camps in Turkey. Seventy percent of the 12,500 men who went in to captivity died on the march and through subsequent ill treatment. Of the 350 men of the 2nd Dorsets captured, only 70 survived their captivity. The Mesopotamian campaign is remembered for the heat of the desert (120° Fahrenheit was common) and the hardship and shameful suffering of many of the wounded. Henry was taken prisoner at Kut and sent to Spim Kara Hassar, Anatolia (modern Asian Turkey) where he died of intestinal inflammation on 24 November 1916. He was aged 36.

On 23 March 1917 the Western Gazette reported "Mrs N Smith, of 1 York Place, Kingston, has received official information that her brother, Private H Hilborne of the Dorsets, had died from intestinal inflammation on 24th November 1916 whilst a prisoner of war at Spim Kara Hassar. Private Hilborne had served 21 years and was in India when war broke out. He was drafted to Mesopotamia, and taken prisoner at Kut with General Townshend’s force."

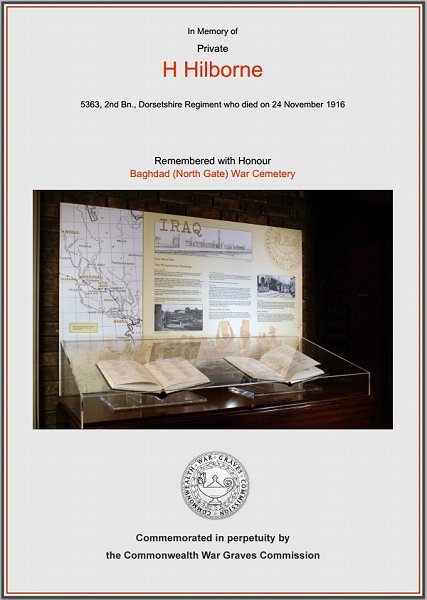

After the end of the First World War Henry Hilborne was re-interred in Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery, Grave XXI.L.22 and his name is recorded on the War Memorial in the Borough, albeit with his name recorded incorrectly as Hillborne (with a double letter 'l') rather than Hilborne (with one 'l')..

gallery

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Harry Hilborne.