yeovil at War

Ernest William Horler

Executed by firing squad for desertion

Ernest William Horler was born in Yeovil on 30 March 1892, the second son of police officer Edward Horler (b1855) originally from Kilmersdon, Somerset, and Sarah née Toole (b1858) originally from Leadgate, Durham. Their first daughter, Mary Jane, was born in Durham in 1877. Their second daughter Florrie was born in Shepton Mallet in 1882 after which the family moved to Yeovil. Their first son George was born in Yeovil in 1886, followed by Ernest in 1892.

Edward Horler died in the 1890s and in the 1901 census his widow Sarah was listed at 35 Huish with Florrie, George and Ernest. Florrie was listed as a glove maker and George was a carpenter while 9-year old Ernest was still at school.

Subsequent to Ernest's later court martial, it was recorded that he was married; however the only possible marriage was at Wincanton in the summer of 1910 when Ernest William Harler was married. Ernest William Horler, with whom we are concerned with here, would only have been aged eight at this time.

In the 1911 census Sarah and Ernest were living with Florrie and her husband Herbert Cook and daughter Vera at 12 Woodland Terrace. 19-year old Ernest was working as a grocer's assistant.

Although

it is not known

where

Ernest enlisted,

he enlisted on

23 May 1916. He

may have joined

the Labour

Battalion (his

conduct sheet

recorded that he

had been absent

for 24 hours on

25 July 1917

'from his

previous unit'

and forfeited 7

days pay). In

any event he was

transferred to B

Company,

12th (Service)

Battalion, West

Yorkshire

Regiment (The

Prince of

Wales’ Own).

His Service

Number was 46127.

Although

it is not known

where

Ernest enlisted,

he enlisted on

23 May 1916. He

may have joined

the Labour

Battalion (his

conduct sheet

recorded that he

had been absent

for 24 hours on

25 July 1917

'from his

previous unit'

and forfeited 7

days pay). In

any event he was

transferred to B

Company,

12th (Service)

Battalion, West

Yorkshire

Regiment (The

Prince of

Wales’ Own).

His Service

Number was 46127.

His regiment had gone to France in September 1915 and by the time Ernest joined them there, they were part of 9th Brigade, 3rd Division. Ernest's battalion took part in an inordinate amount of fighting during 1917, but after this period of hectic fighting the 12th Battalion was withdrawn from the front line for the summer of 1917. However a return to the line found the Battalion taking part in the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge (20 to 25 September 1917) and the Battle of Polygon Wood (26 September to 3 October 1917). Ernest joined his battalion on 2 October 1917, the penultimate day of the Battle of Polygon Wood. Ernest possibly joined with the '80 untrained men from the Labour Battalion', recorded in the Battalion Diary.

The Battle of Polygon Wood was part of the wider Third Battle of Ypres. It came during the second phase of the battle, in which General Herbert Plumer’s Second Army was given the lead. Plumer replaced the ambitious general assaults that had begun the battle with a series of small attacks with limited objectives – his “bite and hold” plan. These attacks involved a long artillery bombardment followed by an attack on a narrow front (2,000 yards wide at Polygon Wood). The attacks were led by lines of skirmishers, followed by small infantry groups. German strong points were to be outflanked rather than assaulted. Each advance would stop after it had moved forward 1,000-1,500 yards. Preparations were then made to fight off any German counterattack. The attack on Polygon Wood was the second of Plumer’s “bite and hold” attacks, after Menin Road.

The final action in which the 12th West Yorkshire Regiment took part was the Battle of Cambrai (20 November – 7 December 1917). This was a British campaign of the latter stages of the Great War. Cambrai, in Nord-Pas-de-Calais, was a key supply point for part of the German Hindenburg Line. The British operation was to include an experimental artillery action and the commander of the British Third Army decided to incorporate British tanks into the attack. Sir Douglas Haig described the object of the Cambrai operations as the gaining of a 'local success by a sudden attack at a point where the enemy did not expect it' and to some extent they succeeded. The proposed method of assault was new, with no preliminary artillery bombardment. Instead, tanks would be used to break through the German wire, with the infantry following under the cover of smoke barrages. The attack began early in the morning of 20 November 1917 and initial advances were remarkable. However, by 22 November, a halt was called for rest and reorganisation, allowing the Germans to reinforce. From 23 to 28 November, the fighting was concentrated almost entirely around Bourlon Wood and by 29 November, it was clear that the Germans were ready for a major counter attack. During the fierce fighting of the next five days, much of the ground gained in the initial days of the attack was lost. For the Allies, the results of the battle were ultimately disappointing but valuable lessons were learnt about new strategies and tactical approaches to fighting. The Germans had also discovered that their fixed lines of defence, no matter how well prepared, were vulnerable.

However, at his final court martial it was recorded "He has been in one action only whilst serving with this battalion. Most of his time has been spent under arrest or as an absentee."

![]()

On 3 December 1917 Ernest deserted. He was court-martialed, sentenced to death and shot on 17 February 1918 - the day his battalion was disbanded.

For a complete account of Ernest Horler's trial, written by Jack Sweet, - click here.

Of course, with hindsight of the past hundred years and changes in attitude during that time, we now understand and accept the terrible effects of war on the minds of combatants and the very real effects of "shell-shock" or combat-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. In 1918 however it was a different matter.

Having said that, Ernest Horler didn't have the cleanest of military records; his conduct sheet, produced at his court martial, revealed that he had been absent from his previous unit for 24 hours on 25 July 1917 and forfeited 7 days pay. Three days later on 28 July he disobeyed a lawful command and was sentenced by a Field General Court Martial to 56 days No 1 Field Punishment. On 8 November a Field General Court Martial had sentenced him to two years Hard Labour for escaping and being absent without leave, but this was reduced to 90 days No 1 Field Punishment; Ernest Horler was still under this sentence when he deserted on 3 December 1917. However, in mitigation, it has been suggested that Ernest may have been mentally impaired.

Nevertheless the case of Ernest Horler was raised in Parliament and reported in the press "Another soldier shot.... was also described as being mentally weak. The man in question, a conscript, had been executed on the day that his battalion was disbanded. Of course, the execution had no bearing on the disbandment of the unit but in the aftermath of the event, questions were asked in the House. The soldier, identified only as Private EH No 46127, West Yorkshire Regiment, had been shot on 17 February. Had the War Cabinet's directive to use the newly printed form for notifying such a death had been followed, then the issue would never have arisen. As it turned out, Number 2 Infantry Record Office at York had blundered by following the old established practice, and as a result the soldier's mother had had her allowance cut. In the ensuing Parliamentary debate, comment was made that the man was regarded by many to be mentally weak, and the House questioned the soldier's mental condition at the time. An assurance was given, however, that both before and after his trial the 26 year old had been specially examined. One further revelation was that the soldier's whereabouts as a deserted had been traced with the assistance of his mother. Whilst at liberty Private Ernest Horler had written to his mother in Yeovil, who in turn had passed the envelopes to the military authorities. As a consequence the soldier was traced. It is not difficult to imagine the grief felt by the dead soldier's relative."

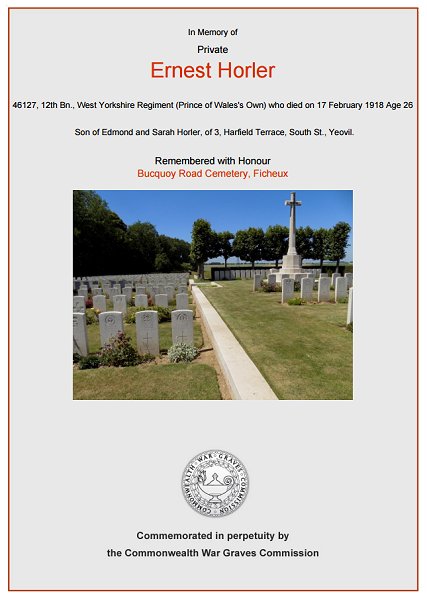

Ernest Horler was buried at the Bucquoy Road Cemetery, Ficheux, Pas de Calais, France. Grave II.L.14.

Of the 200,000 or so men court-martialed during the First World War, 20,000 were found guilty of offences carrying the death penalty; of those, 3000 actually received it, and of those 346 were carried out. The others were given lesser sentences, or had death sentences commuted to a lesser punishment; This might be forced labour, field punishment or a suspended sentence (91 of the men executed were under suspended sentence: 41 of those executed under suspended death sentences, and one had been sentenced to death (and had the sentence suspended) twice before). Of the 346 men executed, 306 were pardoned; the remaining 40 were those executed for mutiny or murder, who would have been executed even under civilian law.

Britain was one of the last countries to withhold pardons for men executed during World War I. In 2007, the Armed Forces Act 2006 was passed allowing the soldiers to be pardoned posthumously, although section 359(4) of the act states that the pardon "does not affect any conviction or sentence."

He is commemorated by the 'Shot at Dawn' Memorial, National Memorial Arboretum, Staffordshire (see below). His name was added to the War Memorial in the Borough in 2018.

gallery

Woodland Terrace, Mill Lane, where Ernest spent his youth. Photographed in 2016.

Ernest Horler's Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Ernest Horler.