yeovil people

robert jennings

Ironmonger, Postmaster & Portreeve of Silver Street

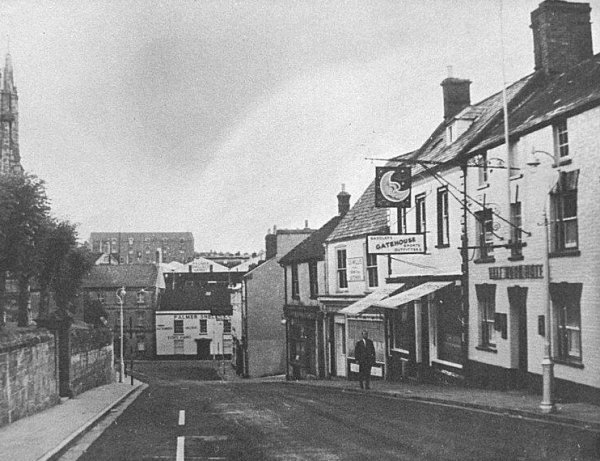

Robert Jennings was born in 1771 in Yeovil and from 1785 until his death he lived in Silver Street. He was an ironmonger and had a shop in Silver Street next-door-but-one to the Half Moon Inn. He was listed in the UK Land Tax Redemption Register of 1798 as an occupier of a property owned by a Mrs Hayne with an assessed annual value of ten guineas (around £11,000 at today's value).

An indenture dated 23 March 1798 recorded that Robert Jennings paid £21 to Grace Foot, widow of James Foot, and their son John Hubert Foot "for all that messuage or dwelling house, garden, backside in Yeovil at Pitt Lane next to Richard Mines on the east and the lands formerly of John Clarke on the west, Pitt Lane on the north – length north to south 90ft width east to west 23ft."

On 13 February 1812, according to the British Postal Service Appointment Book, he became Yeovil's postmaster - the previous incumbent, Gabriel Baker, having been dismissed - and Jennings' ironmongery shop in Silver Street became Yeovil's Post Office. In 1819, Jennings gave evidence in a Parliamentary enquiry into the dwellings against the churchyard wall in Silver Street.

Robert Jennings was listed as a brick maker in Pigot's Directory of 1822 although years earlier an indenture in my collection dated 2 July 1814 shows him to have purchased from Yeoman farmer Samuel Isaac, a brickyard for the sum of £201 5s (around £150,000 at today's value) on land to the south of land he already owned for the "absolute purchase of the same piece or parcel of land with the Brick Kiln and other new erections and buildings now standing and being thereon". The land was described as "All that piece or parcel of arable land containing by estimation one acre.... situate lying and being in Gorefield (Goar Knap) in the parish of Yeovil aforesaid lately converted into a Brickyard bounded on the north by the land of the said Robert Jennings and on the South by lands of James Tucker together with the Brick Kiln and all and singular other outhouse and buildings lately erected and built by the said Samuel Isaac and now standing and being thereon....".

His elder son, Robert Jnr, became an articled clerk in 1822 and later qualified as a solicitor while his younger son, William, carried on the ironmongery business as well as being postmaster after the death of his father.

Robert Jennings was listed as a plumber & glazier in the Universal British Directory of 1790 and was recorded in the Churchwardens' Accounts almost annually as a plumber & glazier between 1790 and 1840. The Churchwardens' Accounts noted on 4 April 1831 Robert Jennings paid 6s 8d for "1 Yrs Rent for a House in Wine Street late Caymes". He had his main ironmongery shop in Silver Street (where he lived above his shop) and separate premises, a lumber yard, in Grope Lane (today's Wine Street). He had three separate listings in Pigot's Directory of 1824 - as an ironmonger, a plumber & glazier and as postmaster - in Silver Street. These listings were repeated in Pigot's Directory of 1830 and Hunt & Co's Directory of 1840. He was listed in the 1827 Jury List but did not appear in the Poll Books of 1832 or 1834.

An indenture dated 3 August 1829 in my collection is interesting as it refers to the lease of properties leased for one year by Robert Jennings 'Plumber & Glazier' to Glove Manufacturer William Snook. It also shows that Jennings built several houses on the site. The indenture refers to "All that Piece or Parcel of Arable Land containing one acre (more or less) lying in a certain Common Field called Gore Field (Goar Knap) in Yeovil aforesaid bounded on the east by Lands belonging to William Helyar Esquire on the west by Brickyard Lane (today's St Michael's Avenue) on the North by Lands belonging to Mrs Callan and on the South by the piece or parcel of Land hereinafter described And also all those several Messuages Dwellinghouses or Tenements and Premises which have been erected thereon by the said Robert Jennings And also All that piece or parcel of Arable Land containing by estimation one Acre (be the same more or less) situate lying and being in Gore Field aforesaid sometime since converted into a Brick Yard bounded on the north by the said piece or parcel of Land Hereinbefore mentioned and described on the South by Lands of James Tucker on the east by the said Lands of the said William Helyar Esquire and on the west by Brickyard Lane aforesaid with the Brick Kiln and all and singular other the erections and buildings now standing or being thereon All which said premises are now in the possession or occupation of the said Robert Jennings or his undertenants....".

Robert Jennings was also deeply involved in the political life of Yeovil and held the post of Portreeve from 1827 until 1838 - an unusually long term of office and, indeed, technically 'irregular'. His tenure, however, was not without its problems primarily because he was patently against the development of modern social and political reform in Yeovil. Further, it would appear that his intentions were self-serving, if not completely corrupt, and he appears to have been a complete luddite in the sense that he opposed change on the basis that it was different from his personal opinion. In consequence, much of the story of Yeovil's attainment of municipal status is repeated here in order to highlight Jennings' position and his active opposition to Yeovil's struggle to become a municipal corporation.

In 1830 parliamentary authority was sought and granted for 'Improvement Commissioners' whose prime purpose would be to attend to the lighting, watering and cleansing of the town. A Bill was passed in June 1830 and the body known as the "Commissioners for Improving the Town of Yeovil" were created. One of the first things the new Commissioners arranged was a rate to be levied in order to pay for their improvements. Robert Jennings, the Portreeve and by now considered to be something of an 'Old Guard' figure, led a deputation of aggrieved tradespeople of the town demanding a petition for the repeal of the 1830 Act or, at the very least, a substantial reduction in the new rate. Although the Commissioners strongly opposed any attempt to reform the Act they did promise to consider a reduction in the rate. In the event nothing happened and the protest quietly came to an end.

During this time of social reforms Robert Jennings, in his role as Portreeve, received an open letter from thirty gentlemen and manufacturers of the town, twenty-three of whom were new Town Commissioners, requesting him to call a public meeting to petition Parliament to create an enquiry into the Old Yeovil Corporation and its workings. Jennings, however, refused claiming that the burgesses would "preserve their rights and privileges". According to Hayward "Thomas Fooks, a Commissioner and glove manufacturer, immediately took the lead in convening a public meeting in spite of the Portreeve's obstruction. A group of leading townsmen stage-managed this meeting in March 1833, securing proposers and seconders for four resolutions to be put to the meeting under the chairmanship of a prominent banker and solicitor, WL White. The first affirmed the need for an enquiry into Yeovil Corporation, the second proposed a petition to the House of Commons so that the abuses of the Old Corporation could be investigated by the newly appointed Royal Commission on Municipalities; the third laid the petition before the meeting and the fourth set up a Corporation Committee to further its object. Twelve members were appointed, nine of them Commissioners, of whom one was their chairman (John Ryall Mayo) and another a solicitor (James Tally Vining, a partner of Slade and Vining of Church Lane)."

The Corporation Committee, headed by solicitor John Batten who was Clerk to the Commissioners, prepared a report which was presented to the Royal Commission on Municipal Corporations in London. It outlined the poor management of the town by the Old Corporation, denigrated Robert Jennings' tenure of the position of Portreeve for ten years as highly irregular and attacked the five burgesses of Yeovil as being unrepresentative of the people and completely unable to provide even the basic services now required by the growing town. The report recommended an elective body replace the Old Corporation, with full municipal powers over the whole town rather than just the small medieval Borough.

In June 1835 the Municipal Corporations Reform Bill was discussed in the House of Commons although Yeovil was not included. The Yeovil Corporation Committee immediately petitioned Parliament for Yeovil's inclusion in the bill and called a public meeting in the town to outline and discuss the proposed recommendations put forward to Parliament. Portreeve Jennings, however, incensed and in fear of losing his power, ordered the Town Crier to read aloud the following notice throughout the town "The rate-payers of this town are reminded that a meeting will be held at the Three Choughs Inn at 11 o'clock this morning: every rate-payer is expected to attend as his rights and privileges are in danger: at the same time the inhabitants must prevent the Yeovil Town Commissioners from nominating themselves as a Town Council, or they will be saddled with a Corporation Rate far worse than the present Town Rate." Nevertheless the public meeting demonstrated the town's full support for the action of the Corporation Committee and in July a petition was presented to Parliament by the two oldest burgesses, both of whom were former Portreeves, John Greenham and George Wellington.

In August it was discovered that Yeovil had again been deleted from the list of boroughs covered by the Bill. Yet again Jennings refused to call a public meeting although one was quickly convened by leading townsmen, supported by the radical Yeovil Political Union. A further petition was organised and both Parliament and the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, were lobbied once again by two Somerset MPs. Yeovil's case for political reform was further hindered when, at the beginning of September, the House of Lords agreed that Yeovil should be omitted from the Bill. It transpired that Jennings and the Burgesses, in order to selfishly protect their own out-dated institution, had been carrying out lobbying of their own and in October 1835 the Western Flying Post reported that "The Portreeve of Yeovil has shown more dexterity than all the blunder-headed Town Clerks who spent their money in endeavouring to lead the country by the nose. The Portreeve only took the two noble lords that we have named (Lords Devon and Buccleugh) between his fingers and they have certainly answered his purpose admirably." For the time being Robert Jennings' self-serving actions had prevented Yeovil from achieving municipal status and had firmly quashed the desires of the majority of the townspeople for political and social reform.

In 1835 the Portreeve's Almshouse was completely rebuilt, costing over £500 which included the rent for temporary accommodation for the four poor women during the rebuilding works. Jennings made a claim against the Corporation in the sum of £436, having already paid the contractor's bill for the rebuilding of the Almshouse, plus a solicitor's bill for £100. When payment was not forthcoming Jennings took it upon himself to advertise the sale of a property owned by the Corporation. An injunction was brought against Jennings by George Wellington to prevent the sale.

But Jennings was far from finished and a scandal over his shady dealings came to a head when, without consultation, he decided to sell off all the properties belonging to the Yeovil Corporation in the summer of 1835.

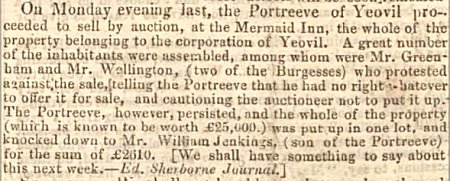

Western Times, 3

October 1835

These comprised some thirty dwellings throughout the town as well as the Court House, also known as the Church House, in the Borough and plots of land in Goldcroft and Horsey Lane. Jennings produced a handbill advertising the sale of the properties by auction which duly took place on 28 September 1835 despite Jennings receiving legal advice against the sale. The whole of the properties were bought by his son William for the sum of £2,610 (just under £2 million at today's value) although the sale was eventually vetoed by two burgesses who claimed the value of the properties to be at least £25,000 (about £19 million at today's value). William Jennings later claimed not to have brought the properties and even wrote a letter to the Western Flying Post denying his involvement in the affair.

In October 1835, at the Court Leet, three nominations were received for the office of Portreeve with one of the nominees to be selected by the Lord of the Borough. Despite being asked twice to attend, Jennings refused to attend the Court Leet and James Curtis was sworn in as the new Portreeve. Jennings, however, refused to hand over the Borough seal, mace and other insignia claiming that the Leet's election of Curtis as Portreeve was illegal since he, Jennings, had not been present. Curtis then began legal proceedings against Jennings and in May the following year the court issued a writ demanding the return of the insignia. The case, suffering delay after delay, dragged on for years. In 1840, during the court proceedings, attempts were made to settle the matter once and for all. Town Commissioner Josiah Hannam, an ironmonger of the Borough, proposed to the Corporation a settlement of £750 to Jennings in order for him to return the mace and seal. Although the settlement was agreed by the three surviving town Burgesses, Jennings refused the offer. In fact at this time Jennings, unknown to the Burgesses, was negotiating with solicitor John Batten who offered Jennings an immediate loan of £100 and a further £650 providing Jennings stopped the Chancery proceedings and agreed to Batten being appointed Portreeve. Nothing, however, came of these secret negotiations.

Late in 1840, Jennings finally agreed to meet with the Corporation. He and his attorney, John Batten, met with the other Burgesses and their solicitor, James Tally Vining. At long last Jennings promised to resign the office of Portreeve and return the Corporation's mace and seal in return for the sum of £750. All the legal formalities were finally completed in 1841 and Jennings received his money although Vining reported that Jennings was "a man of little or no available property after payment of debts".

Robert Jennings died in Yeovil in the summer of 1848, aged 77. His ironmongery business and the position of Yeovil's postmaster went to his son, William, but Robert Jennings was long remembered for his unseemly obstruction of social and municipal reform in Yeovil.

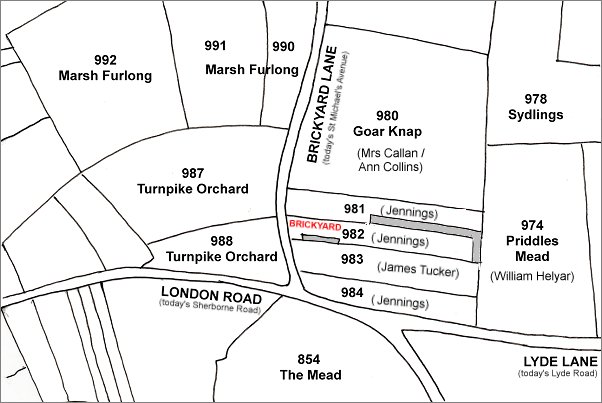

Jenning's brickyard is now the site of the old White Horse (now converted to flats) in St Michael's Avenue.

Map

This map, based on the 1842 Tithe Map, shows the parcels of land referred to in the indentures of 1814 and 1829 above. Parcel 982 was that parcel "lately converted into a Brickyard", Parcel 981 contained New Prospect Place built and owned by Robert Jennings (his son William had inherited the lands by 1846) - "bounded on the north by the land of the said Robert Jennings". Parcel 983 was "on the South by lands of James Tucker" - this is now the site of Great Western Terrace.

GALLERY

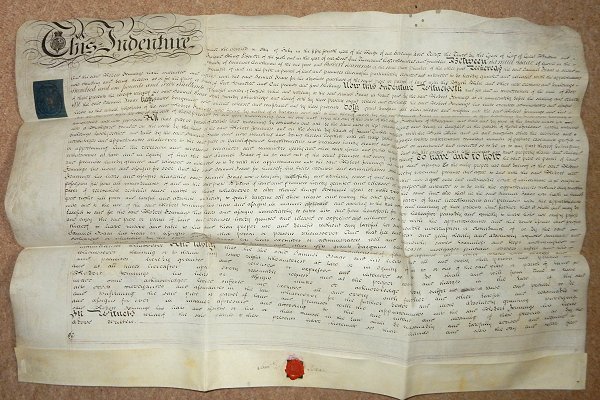

From my

collection

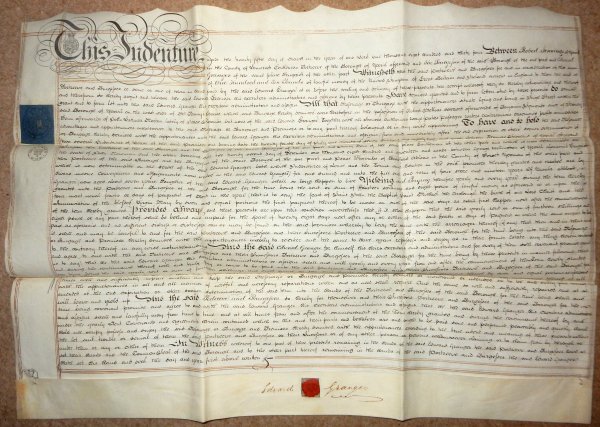

The indenture dated 2 July 1814 in which Robert Jennings bought the brickworks from Samuel Isaac for £201 5s.

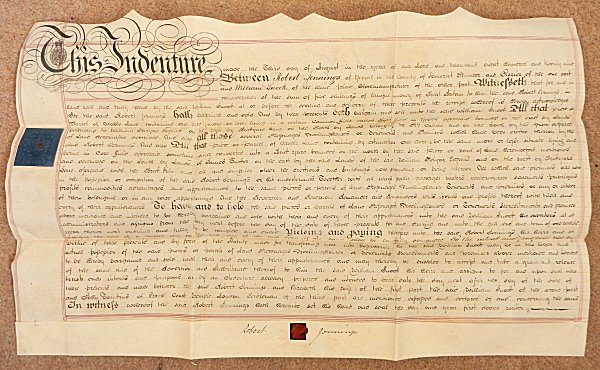

From my

collection

The indenture dated 3 August 1829 referred to above in which he leased out the brickyard as well as several houses he had built on the site.

From my

collection

The signature and seal of Robert Jennings from the 1829 indenture above.

From my

collection

An indenture, dated 25 March 1834, in which Edward Granger leased a High Street property owned by the Corporation (the former Fleur de Lys) from Robert Jennings, Portreeve of the Corporation at the time.

This photograph of about 1960 looks down Silver Street with the Half Moon Inn at extreme right with the building that housed Robert Jennings' ironmongery shop and Yeovil's second post office next door but one (next to the shop with the awnings).