yeovil at War

Ernest Gatehouse

Died of wounds, New Years Day 1918

Ernest Gatehouse was born in 1892 in Yeovil, the son of harness maker Frank Gatehouse (1856-1928), originally from Shaftesbury, Dorset, and Jane née Hallett (1854-1930), originally from Seavington. Frank and Jane had moved around a bit during their marriage; their first child was born in Yeovil, the next three were born in Martock and the last three, including Ernest, were born in Yeovil.

The 1901 census listed the family at 2 Brunswick Street (see photo below); Frank and Jane's children were Cecil Frank (1886-1951), Kate Marina (1887-1960), William Raymond (1889-1949), Maud Phelps (1891-1954), Ernest (1892-1918), George (1895-1953) and Sidney James (1899-1954). Their last son, Wilfred Harry (1904-1992), was born after the census. The family were still at the same address in the 1911 census by which time 18-year old Ernest described his occupation as a Printer's Apprentice. He worked at the Western Chronicle office in Middle Street.

In late 1914, at the age of 22, Ernest married Ada Laura Blades at Poole. They set up home at 'White Heather', St Mary's Road, Bournemouth

It

is not known

when Ernest

enlisted, but he

enlisted at

Poole, Dorset.

It was probably

during 1915 or

1916 judging by

his Service

Number 25715. He

joined the 1st

(Regular)

Battalion of the

Hampshire

Regiment.

It

is not known

when Ernest

enlisted, but he

enlisted at

Poole, Dorset.

It was probably

during 1915 or

1916 judging by

his Service

Number 25715. He

joined the 1st

(Regular)

Battalion of the

Hampshire

Regiment.

William enlisted in the army at Winchester, at the age of 18 - his Service Number 7697 indicating that he enlisted in September 1906 in the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment.

The Battalion was part of 4th Division and had been in France since August 1914 as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and almost immediately entered a series of battles.

Since it is not known when Ernest joined the Battalion it is not known in which of the earlier battles he took part. However he was almost certainly with the Battalion during 1917 and the following engagements - the First and Third Battles of the Scarpe, the Battle of Polygon Wood, the Battle of Broodseinde, the Battle of Poelcapelle, and the First Battle of Passchendaele.

Zero-Hour for the First Battle of the Scarpe had originally been planned for the morning of 8 April (Easter Sunday) but it was postponed 24 hours at the request of the French, despite reasonably good weather in the assault sector. Zero-Day was rescheduled for 9 April with Zero-Hour at 05:30. The assault was preceded by a hurricane bombardment lasting five minutes, following a relatively quiet night. When the time came, it was snowing heavily; Allied troops advancing across no man's land were hindered by large drifts. It was still dark and visibility on the battlefield was very poor. A westerly wind was at the Allied soldiers' backs blowing "a squall of sleet and snow into the faces of the Germans". The combination of the unusual bombardment and poor visibility meant many German troops were caught unawares and taken prisoner, still half-dressed, clambering out of the deep dug-outs of the first two lines of trenches. Others were captured without their boots, trying to escape but stuck in the knee-deep mud of the communication trenches. Most of the British objectives had been achieved by the evening of 10 April though the Germans were still in control of large sections of the trenches between Wancourt and Feuchy.

The Third Battle of the Scarpe, the last of the Battles of Arras, 1917, which opened on 3 May, was of a similar nature to the operations of 28 and 29 April. The French had planned a heavy attack on Chemin des Dames to take place on the 5th and, in order to distract the attention of the enemy and hold his troops east of Arras, Sir Douglas Haig considerably extended his active front. While the Third and First Armies attacked from Fontaine-les-Croisilles to Fresnoy the Fifth Army was to launch a second attack upon the Hindenburg Line in the neighbourhood of Bullecourt - a total of over 16 miles. Zero hour was timed for 3:45am on 3 May. In these final operations the 4th Division was engaged. The 1st Battalion Hampshires had not been engaged with the enemy after the close of the First Battle of the Scarpe on 14 April. The 14th Division having relieved the 4th Division on 20 April.

The Battle of Polygon Wood, 25-27 September 1917, was part of the wider Third Battle of Ypres. It came during the second phase of the battle, in which General Herbert Plumer’s Second Army was given the lead. Plumer replaced the ambitious general assaults that had begun the battle with a series of small attacks with limited objectives – his “bite and hold” plan. These attacks involved a long artillery bombardment followed by an attack on a narrow front (2,000 yards wide at Polygon Wood). The attacks were led by lines of skirmishers, followed by small infantry groups. German strong points were to be outflanked rather than assaulted. Each advance would stop after it had moved forward 1,000-1,500 yards. Preparations were then made to fight off any German counterattack. The attack on Polygon Wood was the second of Plumer’s “bite and hold” attacks, after Menin Road. It was carried out chiefly by the 4th and 5th Australian Divisions but the 1st Battalion, Hampshires also played a part. The site of Polygon Wood was captured on 26 September, the target line on 27 September. The attack then stopped, and Plumer prepared for the next attack. The two Australian divisions lost 5,471 men during the Battle of Polygon Wood. The three “bite and hold” attacks brought the front line to the foot of the Passchendaele Ridge, which would be come the target of the First and Second Battles of Passchendaele, and give its name to the entire battle.

The Battle of Broodseinde, 4 October 1917, was the last of three successful “bite and hold” battles launched by General Herbert Plumer during the middle phase of the Third Battle of Ypres. Both sides were planning an attack on 4 October. When the British bombardment began, it caught a number of German units out in the open preparing for their own attack. The British attack contained divisions from Britain, New Zealand and Australia. As at Menin Road Ridge and Polygon Wood, the British attack achieved its main objectives and then halted to dig in. Although these attacks are normally described as small scale battles, the casualty figures demonstrate the real scale of the fighting. The Germans suffered 10,000 casualties and lost 5,000 prisoners. On the Allied side the Australians suffered 6,432 casualties, the New Zealanders 892 and the British 300.

The Battle of Poelcappelle (9 October 1917) marked the end of the string of highly successful British attacks in late September and early October 1917, during the Third Battle of Ypres. Only the supporting attack in the north achieved a substantial advance. On the main front the German defences withstood the limited amount of artillery fire managed by the British after the attack of 4 October. The ground along the main ridges had been severely damaged by shelling and rapidly deteriorated in the rains, which began again on 3 October, which in some areas turned the ground into a swamp. Dreadful ground conditions had more effect on the British, who needed to move large amounts of artillery and ammunition to support the next attack. The battle was a defensive success for the German army, although costly to both sides.

The First Battle of Passchendaele took place on 12 October 1917 in the Ypres Salient of the Western Front, west of Passchendaele village, during the Third Battle of Ypres. The Allied plan was to capture Passchendaele village. This was based on the incorrect assumption that during the Battle of Poelcappelle, three days previous, the attacking troops had captured the first objective line. In fact, the Allied front line near Passchendaele had hardly changed and the true position of the Allied front line, meant that the planned advance of 1,500 yards (1,400 m) was actually 2,000–2,500 yards (1,800–2,300 m). The assault was directly south of the inter-army boundary between the British Fifth and Second Armies and consequently pitted a collection of formations from both armies against the German Fourth Army. Despite advances on the northern front of the battlefield, the German's retained control of the high ground on Passchendaele Ridge and consequently the attack failed in attaining its principal objective. Although the battle was costly to both sides, the battle was considered a German defensive success. Further British attacks were postponed until the weather improved and communications behind the front had been restored.

Following this series of battles the intensity of fighting lessened somewhat although the landscape remained extremely dangerous and day-to-day fighting took a tremendous toll on both sides. Edward was wounded three times in as many months after these 'set' battles, the final wound being received on 10 December. Sadly Edward died from his wound on 1 January 1918. He was aged 25.

On 11 January 1918 the Western Gazette reported "The parents of Private E Gatehouse, Silver Street, have been notified that their son has died of wounds received in action. Private E Gatehouse was seriously wounded on December 10th and admitted to a Casualty Clearing Station in France. He was formerly employed by the “Western Chronicle” Office, and, on leaving Yeovil some few years ago, went to Bournemouth, where he was well-known. He was on leave about a month ago. He had twice before been wounded, and the three occasions were all within three months. Great sympathy is expressed with the widow, the bereaved parents and all other relatives. (Husband of Ada Laura Gatehouse, of “White Heather,” St Mary’s Road, Bournmouth)"

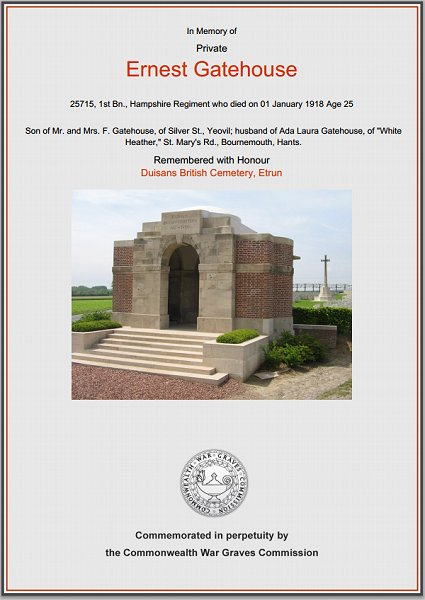

Ernest Gatehouse is interred in Grave V.E.8, Duisans British Cemetery, Etrun, Pas de Calais, France and his name is recorded on the War Memorial in the Borough.

gallery

This

colourised photograph

features in my

book "Lost Yeovil"

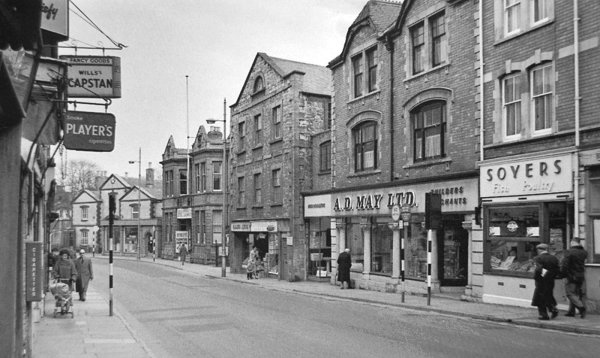

A postcard dated 1906 looking along Brunswick Street with Brunswick Place and Brunswick Terrace at left. At the time the Gatehouse family lived there. Their house would have been further left, just behind the photographer.

In this photograph of the mid-1960s, the former Western Chronicle building, where Ernest worked before going off to war, is seen at centre sandwiched between the Liberal Club and AD May's builders merchants.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Ernest Gatehouse.