yeovil at War

William Charles Smith

Killed in action during a trench bombardment

William Charles Smith was born in Yeovil on 29 July 1891, the son of leather dresser Henry Charles Smith (1866-1927), originally from Closworth, and glove backer Mary Jane née Barge (1866-1944) of Yeovil. Henry and Mary were to have ten children, all born in Yeovil; Ellen Augusta (b1889), Kate (b1890), William Charles, Ernest (1893-1972), Alfred (b1894), Bessie (b1895), Mabel (b1897), Robert Charles (1898-1962), Edith (b1904) and Charles (b1906).

In the 1901 census Henry, Mary and seven of the children were listed at 34 Kiddles Lane (today's Eastland Road). Henry gave his occupation as a leather dresser and Mary gave hers as a glove backer.

On 30 July 1906, the day after his fifteenth birthday, William started work at Yeovil Town Station as an engine cleaner. On 3 October 1910 his job was transferred to Taunton where he worked in the shunting yard as a shift fireman at a rate of three shillings. The 1911 census recorded William lodging at 10 Maxwell Street, Rowbarton, Taunton, with the family of Samuel Ling. William gave his occupation as 'Railway Loco Fireman'.

During 1911 he was promoted to Fireman 3rd Class and his pay increased to 3s 6d. The railway company's records also show that on 24 September 1911 William had a slight accident while working at Bristol when "On arrival of train, Smith was proceeding to Signal Box when his foot turned on edge of a sleeper. Left ankle sprained. Resumed duty 16 October 1911."

On 4 October 1912, at the age of 21, William "Resigned to go abroad". He emigrated to Canada.

On

26 November

1915, at

Winnipeg,

William enlisted

in the Canadian

Over-Seas

Expeditionary

Force. He listed

his address as

Crandall,

Manitoba and

gave his trade

in Canada as a

farm labourer.

His attestation

papers also

noted that he

was 5ft 8in

tall,

fair-haired with

a fair

complexion and

blue eyes and

had a birthmark

on his back. The

form also

recorded that

William was a

Methodist.

On

26 November

1915, at

Winnipeg,

William enlisted

in the Canadian

Over-Seas

Expeditionary

Force. He listed

his address as

Crandall,

Manitoba and

gave his trade

in Canada as a

farm labourer.

His attestation

papers also

noted that he

was 5ft 8in

tall,

fair-haired with

a fair

complexion and

blue eyes and

had a birthmark

on his back. The

form also

recorded that

William was a

Methodist.

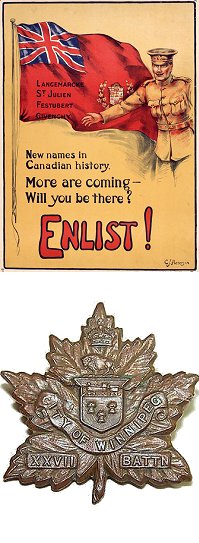

William was initially enlisted as a Private in the 90th Canadian Infantry Battalion (Winnipeg Rifles). His Service Number was 186246. He was later transferred to the 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg), Manitoba Regiment of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg), CEF was an infantry battalion, authorized on 7 November 1914 and embarked for Great Britain on 17 May 1915.

After his basic training William and his battalion landed in France on 18 September 1915, where the battalion fought as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division in France and Flanders until the end of the war.

The Canadian Corps, including the 27th, would not participate in any major offensive for many months. The Battalion received its 'baptism of fire' at the Battle of St Eloi Craters, fought from 27 March to 16 April 1916. The attack took place over the muddy terrain of Belgium and was the first major engagement for the 2nd Canadian Division. It was a disaster for Canada and its Allies.

Since late 1915, armies on both sides had been using extensive mining as a part of trench warfare. Sappers dug tunnels across the battlefield to plant explosives under enemy positions and would then retreat and blow them up. The fields near the Belgian village of St Eloi, located five kilometres south of Ypres, were pockmarked with craters as shown in the Gallery below from repeated underground explosions.

In the spring of 1916, the Canadian Corps’ 2nd Division was sent to fight Germans on the front line at St Eloi but they were rushed to the battlefield, leaving no time to prepare for the attack. The plan was for the seasoned British troops to strike and then for the Canadians to take over and hold the line.

The fighting started at 4:15am on 27 March with heavy gun fire. Six British mines were set off one after the other, shaking the earth “like the sudden outburst of a volcano” and filling the sky with yellow smoke and debris, according to the Canadian Expeditionary Force's war record. The explosion was heard in England as German trenches collapsed into the craters. British troops fought from inside the craters, crouching in mud or standing in waist-deep water, unable to sit. High winds, sleet and mud created nightmarish conditions. Hundreds of men were killed on either side in a week of chaotic shooting and shelling.

The exhausted British were relieved by the Canadians at 3am on 4 April 1916. The entire front line came under constant bombardment on 4 and 5 April, and hundreds more men were killed. Canadian Private Donald Fraser, described the scene: “When day broke, the sights that met our gaze were so horrible and ghastly that they beggar description. Heads, arms and legs were protruding from the mud at every yard and dear knows how many bodies the earth swallowed. Thirty corpses were at least showing in the crater and beneath its clayey waters other victims must be lying killed and drowned.” Another Canadian wrote to his wife that “we were walking on dead soldiers” as they tried to advance. Wounded and traumatized men streamed back to the medical officers. Some had been fighting standing in cold water and mud for 48 straight hours.

Both sides shot at each other in the miserable conditions of the craters for another two weeks. More than 1,370 Canadians were killed or wounded, along with about 480 Germans. Aerial photography on 16 April finally showed the Canadians that they were in a terrible position, and the divisional headquarters ordered the battle stopped. The Battle of St. Eloi’s Craters ended with the Germans in control of the battlefield, as they had been at its start.

The Somme Valley became the new objective of the Canadian Corps. When the Canadians arrived in the Somme Valley the British had been fighting for three months and they had traded 250,000 men for 8 kilometres of German trenches. On the opening day of the Somme offensive alone, 1 July 1916, around 20,000 British, Canadian and Commonwealth soldiers died and another 40,000 were wounded.

One of the most notable battles of Somme the 27th Battalion participated in was the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, again within the first Somme Offensive. The battle began on 15 September 1916 and continued for a week. Flers–Courcelette began with the objective of cutting a hole in the German line by using massed artillery and infantry attacks. This hole would then be exploited with the use of cavalry. By its conclusion on 22 September, the strategic objective of a breakthrough had not been achieved; however tactical gains were made in the capture of the villages of Courcelette, Martinpuich and Flers. In some places, the front lines were advanced by over 2,500 yards (2,300 m) by the Allied attacks. The battle is significant for the first use of the tank in warfare although all six tanks that used that day were knocked out. It also marked the debut of the Canadian and New Zealand Divisions on the Somme battlefield. The Canadians suffered around 7,000 casualties during the battle.

Between 26 and 28 September 1916 the 27th Battalion became embroiled in the Battle of Thiepval Ridge, again a battle within the Somme Offensive. The battle was fought on a front from Courcelette in the east, near the Albert–Bapaume road to Thiepval and the Schwaben Redoubt in the west, which overlooked the German defences further north in the Ancre valley, the rising ground towards Beaumont-Hamel and Serre beyond. Thiepval Ridge was well fortified and the German defenders fought with great determination. The attack on 26 September was a mixed success. On the right, the Canadians captured their limited objectives in the first attack. On the left, the 34th Brigade of the 11th Division suffered very heavy losses and failed to make any real progress. In comparison the 33rd brigade suffered 600 casualties; most of them wounded, and took most of their objectives.

After just a few days respite the 27th Battalion fought in the Battle of the Ancre Heights from 1 October to 11 November 1916. Between 1 and 8 October the Canadian Corps assaults on Regina Trench witnessed brutal fighting, heavy casualties and temporary limited occupation of the objective. Canadian attempts on 23 October further to extend their occupation of Regina Trench were frustrated by mud and heavy enemy fire. It was not until 10 November, after days of rain, that a surprise midnight assault finally secured the eastern portion of this position. The Battle of the Ancre represented the end of the Battle of the Somme, including Ancre Heights, and concluded with the capture of Beaumont Hamel, St Pierre Divion and Beaucourt.

After some three months of heavy fighting, William was killed in his trench by a German trench bombardment during 27 November 1916. He was 25 years old.

In its edition of 3 December 1916 the Western Gazette reported "The news was received on Wednesday by Mr and Mrs Smith, of Eastland Road, that their eldest son, Private William Charles Smith, of the Canadians, had been killed in action. Private Smith, who was only 23 years of age (William was actually 25), had been in France a little over three months. A letter received from the Chaplain of the Regiment states:- “You have doubtless already heard that your son Private WC Smith fell during a violent bombardment of our trenches last Monday. He was buried the following night in the pretty little soldiers’ Cemetery where a suitable cross bearing his name will be placed on his grave. Let me express my sympathy with you in your bereavement and enter with you into the joy of knowing that your son was found willing to devote his service and sacrifice to the greatest cause which has engaged Christian men. His life and death will be a memory that will grow more frequent as years unfold the importance of the part he and other brave fellows have played in this great struggle on behalf of Christianity.” Much sympathy is felt with Mr and Mrs Smith in their sad loss."

William Smith was interred in Bois-De-Noulette British Cemetery, Aix-Noulette. Grave II.C.8, and his name is inscribed on the War Memorial in the Borough.

gallery

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of William Smith.