yeovil at War

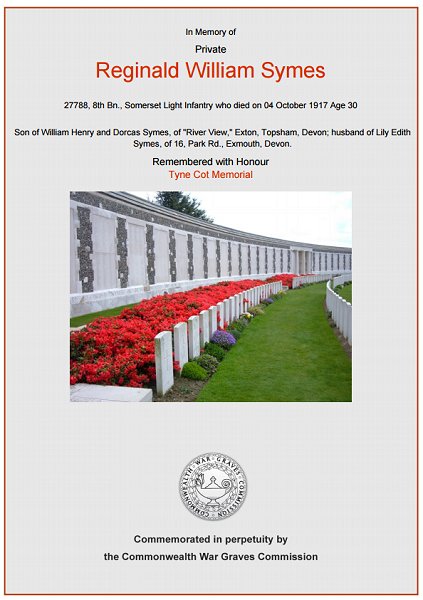

Reginald William Symes

Killed in action during the Battle of Broodseinde

Reginald William Symes was born in Yeovil during the autumn of 1886. He was the son of market gardener Herbert William Symes (1865-1941) and Dorcas née Pike (1861-1938), originally from Starcross, Devon. Herbert and Dorcas had two sons, both born in Yeovil; Reginald and Lionel Albert (1889-1964). By 1891 the family had moved to Station Road, Woodbury, Devon and were still living there in 1901. I couldn't find Reginald in the 1911 census.

In the winter of 1916 Reginald married Lily Edith Dyer at St Thomas (Exeter). They set up home in Exeter just before Reginald enlisted.

Although

it is not known

exactly when

Reginald

enlisted, he

enlisted at

Exeter joining

8th (Service)

Battalion,

Somerset Light

Infantry. His

Service Number,

27788,

suggesting he

enlisted during

late

1916, probably

immediately

after his

marriage to Lily. He was

almost certainly sent to France

on 5 April 1917.

Although

it is not known

exactly when

Reginald

enlisted, he

enlisted at

Exeter joining

8th (Service)

Battalion,

Somerset Light

Infantry. His

Service Number,

27788,

suggesting he

enlisted during

late

1916, probably

immediately

after his

marriage to Lily. He was

almost certainly sent to France

on 5 April 1917.

During 1917 the 8th (Service) Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry were involved in an inordinate amount of fighting including the First Battle of the Scarpe, the capture of Monchy-le-Preux, the Second Battle of the Scarpe, the Battle of Arleux, the Battle of Pilkem Ridge, the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, the Battle of Polygon Wood and the Battle of Broodseinde.

As part of the Arras Offensive the 8th Battalion took an active part in the First Battle of the Scarpe (9 to 14 April 1917), including the capture of Monchy-le-Preux, the Second Battle of the Scarpe (23 to 24 April 1917) and the Battle of Arleux (28 to 29 April 1917). The Arras Offensive was a major British offensive from 9 April to 16 May 1917, troops from the four corners of the British Empire attacked trenches held by the army of Imperial Germany to the east of the French city of Arras.

Zero-Hour for the First Battle of the Scarpe had originally been planned for the morning of 8 April (Easter Sunday) but it was postponed 24 hours at the request of the French, despite reasonably good weather in the assault sector. Zero-Day was rescheduled for 9 April with Zero-Hour at 05:30. The assault was preceded by a hurricane bombardment lasting five minutes, following a relatively quiet night. When the time came, it was snowing heavily; Allied troops advancing across no man's land were hindered by large drifts. It was still dark and visibility on the battlefield was very poor. A westerly wind was at the Allied soldiers' backs blowing "a squall of sleet and snow into the faces of the Germans". The combination of the unusual bombardment and poor visibility meant many German troops were caught unawares and taken prisoner, still half-dressed, clambering out of the deep dug-outs of the first two lines of trenches. Others were captured without their boots, trying to escape but stuck in the knée-deep mud of the communication trenches. Most of the British objectives had been achieved by the evening of 10 April though the Germans were still in control of large sections of the trenches between Wancourt and Feuchy.

On 23 April, the British launched an assault east from Wancourt towards Vis-en-Artois. The British made initial gains but could advance no further east and suffered heavy losses. Farther north, German forces counter-attacked in an attempt to recapture Monchy-le-Preux, but British commanders determined not to push forward in the face of stiff German resistance, and the attack was called off the following day on 24 April.

In the Battle of Arleux (28 to 29 April 1917), although the Canadian Corps had taken Vimy Ridge, difficulties in securing the south-eastern flank had left the position vulnerable. To rectify this, British and Canadian troops launched an attack towards Arleux-en-Gohelle on 28 April. Arleux was captured by Canadian troops with relative ease, but the British troops advancing on Gavrelle met stiffer resistance from the Germans. The village was secured by early evening but, despite achieving the limited objective of securing the Canadian position on Vimy Ridge, casualties were high, and the ultimate result was disappointing. According to the Regimental History of the Somerset Light Infantry "The Battle of Arleux, fought on 28th and 29th of April, the 8th Somersets of the 37th Division again taking part in the operations, though the only Battalion of the regiment to do so. The front of attack was about 8 miles.... The attack of the XVII Corps was to be carried out by the 34th Division on the right and the 37th Division on the left.... Zero hour was 4:25am on 28 April. During the night of 27th/28th the eighth Battalion.... Moved forward from Heron Trench and assembled in Cuba Trench; the Battalion was in position by 3am on 28th, two platoons in front and two in rear, as each attacking battalion had been ordered to advance on a two-platoon frontage. It was so dark when Zero hour arrived that it was impossible to see more than 20 yards ahead, British and Germans being indistinguishable. Compass bearings had been taken and given to officers and NCOs, but even so, when the attack went forward, there was loss of direction. A few minutes after Zero a very heavy hostile barrage fell on the line of the road and the smoke, combined with the darkness, caused considerable confusion, with the result that the Somersets swung off to the left and Cuthbert Trench (directly east of Cuba Trench) was only partially attacked, the full weight of the attack passing on to Whip Trench, which lay some 500 yards east of Cuthbert."

The Battle of Polygon Wood, 25-27 September 1917, was part of the wider Third Battle of Ypres. It came during the second phase of the battle, in which General Herbert Plumer’s Second Army was given the lead. Plumer replaced the ambitious general assaults that had begun the battle with a series of small attacks with limited objectives – his “bite and hold” plan. These attacks involved a long artillery bombardment followed by an attack on a narrow front (2,000 yards wide at Polygon Wood). The attacks were led by lines of skirmishers, followed by small infantry groups. German strong points were to be outflanked rather than assaulted. Each advance would stop after it had moved forward 1,000-1,500 yards. Preparations were then made to fight off any German counterattack. The attack on Polygon Wood was the second of Plumer’s “bite and hold” attacks, after Menin Road. The site of Polygon Wood was captured on 26 September, the target line on 27 September. The attack then stopped, and Plumer prepared for the next attack. The two Australian divisions lost 5,471 men during the Battle of Polygon Wood. The three “bite and hold” attacks brought the front line to the foot of the Passchendaele Ridge, which would be come the target of the First and Second Battles of Passchendaele, and give its name to the entire battle.

The Battle of Broodseinde, 4 October 1917, was the last of three successful “bite and hold” battles launched by General Herbert Plumer during the middle phase of the Third Battle of Ypres. Both sides were planning an attack on 4 October. When the British bombardment began, it caught a number of German units out in the open preparing for their own attack. The British attack contained divisions from Britain, New Zealand and Australia. As at Menin Road Ridge and Polygon Wood, the British attack achieved its main objectives and then halted to dig in. Although these attacks are normally described as small scale battles, the casualty figures demonstrate the real scale of the fighting. The Germans suffered 10,000 casualties and lost 5,000 prisoners. On the Allied side the Australians suffered 6,432 casualties, the New Zealanders 892 and the British 300. Reginald was killed in action on 4 October 1917 during the Battle of Broodseinde. He was 30 years old.

Reginald is commemorated on the Tyne Cot memorial, Panels 41 to 42 and 163A. His name was added to the War Memorial in the Borough in 2018.

gallery

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Reginald Symes.