yeovil at War

Henry Frank Whatley

Fought in an incredible 19 major actions

Henry Frank Whatley, known as Frank, was born in late 1892 at Warminster, Wiltshire, and was baptised at St Denys, Warminster, on 12 March 1893. He was the second of the eleven children of pump fitter Henry George Whatley (1871-1952) and Rose Iris née Whatley (1870-1951). Henry and Rose's children were Hilda Lily, known as Lily (1890-1980), Henry, Mildred May (1896-1972), Wilfred (1898-1954), Percy Alden (1899-1962), Iris Victoria R (b1901), Violet F (b1903), Jesse Edwin (1905-1984), Daisy Selina (1906-1992), Evan Charles (b1910) and Vera Gwen M (1911-1996).

In the 1901 census the family were living at 74 West Street, Warminster and in the 1911 census they were living at 65 West Street. Eighteen-year old Frank gave his occupation as an indoor college servant. Shortly after this the family moved to Yeovil, living at 1 Highfield Road.

Frank

Whatley

enlisted at

Warminster,

Wiltshire in

August 1914,

joining the 6th

(Service)

Battalion, Duke

of Edinburgh's

(Wiltshire

Regiment).

Frank

Whatley

enlisted at

Warminster,

Wiltshire in

August 1914,

joining the 6th

(Service)

Battalion, Duke

of Edinburgh's

(Wiltshire

Regiment).

The 6th Battalion was formed at Devizes as part of Second New Army (K2) and then moved to Salisbury Plain to join the 19th Division. In December 1914 they moved to Basingstoke and joined the 58th Brigade of the 19th Division.

In March 1915 the battalion moved to Perham Down and in July 1915 they were mobilised for war and landed in France. From this time onwards Frank, with his battalion, was engaged in an extraordinary number of actions.

The first of these was the Action of Pietre (25 September 1915), the first day of, and part of, the Battle of Loos. This was the first genuinely large scale British offensive action but was only in a supporting role to a larger French offensive in Champagne. British appeals that the ground over which they were being called upon to advance was wholly unsuitable were rejected. The battle is historically noteworthy for the first British use of poison gas. The battalion then took part in a diversionary action during the Battle of Loos.

A continuous preliminary bombardment, which showered 250,000 shells on to the German defences over four days, had little real effect. Before sending in the infantry on the morning of 25 September 1915, the British released 140 tons of chlorine gas from 5,000 cylinders placed on the front line to make up for the ineffective artillery barrage. This was the first time the Allies had used the weapon, coming after the Germans employed gas to terrible effect at Ypres in April earlier in the year, and it was hoped it would annihilate the Germans at Loos. However a change in the direction of the wind at several points along the front blew the gas back into the British trenches, causing seven deaths and injuring 2,600 soldiers who had to be withdrawn from the front line. Initially the gas attack created panic among the Germans and close to 600 men were gassed. Despite the setbacks caused by the wind 75,000 British infantrymen still flowed out from the trenches when the order came. British losses at Loos were exceptionally high with 50,000 casualties, including at least 20,000 deaths.

The next major action in which the 6th Wilts took part was the first day on the Somme, 1 July 1916, which was the opening day of the Battle of Albert (1–13 July 1916). Nine corps of the French Sixth Army, as well as the British Fourth and Third armies, attacked the German Second Army from Foucaucourt on the south bank to Serre, north of the Ancre and at Gommecourt 2 miles (3.2 km) beyond. The objective of the attack was to capture the German first and second positions from Serre south to the Albert–Bapaume road and the first position from the road south to Foucaucourt. The German defence south of the road mostly collapsed and the French had complete success on both banks of the Somme, as did the British from Maricourt on the army boundary, where XIII Corps took Montauban and reached all its objectives and XV Corps captured Mametz and isolated Fricourt.

After the two weeks of carnage from the commencement of the Somme Offensive, it became clear that a breakthrough of either the Allied or German line was most unlikely and the offensive had evolved to the capture of small prominent towns, woods or features which offered either side tactical advantages from which to direct artillery fire or to launch further attacks. High Wood was one such feature, making it important to German and Allied forces. As part of a large offensive starting on 14 July, General Douglas Haig, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force, intended to secure the British right flank, while the centre advanced to capture the higher lying areas of High Wood in the centre of his line - with the 6th Wilts taking part in the attacks on High Wood.

A subsidiary attack of the Somme Offensive, and launched on 23 July 1916, the Battle of Pozieres Ridge on the Albert-Bapaume road saw the Australians and British (including Frank and the 6th Wilts) fight hard for an area that comprised a first rate observation post over the surrounding countryside, as well as the additional benefit of offering an alternative approach to the rear of the Thiepval defences.

The next major action that involved Frank was the Battle of the Ancre Heights (1 October – 11 November 1916), a continuation of British attacks after the Battle of Thiepval Ridge in September during the Battle of the Somme. The battle was conducted by the Reserve Army from Courcelette near the Albert–Bapaume road, west to Thiepval on Bazentin Ridge. British possession of the heights would deprive the German 1st Army of observation towards Albert to the south-west and give the British observation north over the Ancre valley to the German positions around Beaumont Hamel, Serre and Beaucourt. The Reserve Army conducted large attacks on 1, 8, 21, 25 October and from 10–11 November. Many smaller attacks were made in the intervening periods, amid interruptions caused by frequent heavy rain, which turned the ground and roads into rivers of mud and grounded aircraft.

This was followed immediately by the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November 1916), which was fought by the British Fifth Army against the German 1st Army. The battle was the final large British attack of the Battle of the Somme. The attack was the largest in the British sector since September and had a seven-day preliminary bombardment, which was twice as heavy as that of 1 July. Beaumont Hamel, St Pierre Divion and Beaucourt were captured, which threatened the German hold on Serre further north. Four German divisions had to be relieved due to the number of casualties they suffered and over 7,000 German troops were taken prisoner.

After the Battle of the Ancre, British attacks on the Somme front were stopped during inclement weather and until early January 1917 military operations by both sides concentrated on surviving the rain, snow, fog, mud fields, waterlogged trenches and shell-holes. British operations on the Ancre from 10 January to 22 February 1917, forced the Germans back five miles (8.0 km) on a four mile (6.4 km) front, and eventually took 5,284 prisoners. On 22/23 February, the Germans fell back another three miles (4.8 km) on a fifteen mile (24 km) front.

After the battle Frank, with the 6th Battalion, resumed daily life in the mud of the Somme trenches until his battalion took part in their next set-piece battle, the Battle of Messines.

The Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917) was an offensive conducted by the British Second Army, under the command of General Sir Herbert Plumer, on the Western Front near the village of Messines in West Flanders, Belgium. The offensive at Messines forced the Germans to move reserves to Flanders from the Arras and Aisne fronts, which relieved pressure on the French. The tactical objective of the attack at Messines was to capture the German defences on the ridge, which ran from Ploegsteert (Plugstreet) Wood in the south, through Messines and Wytschaete to Mount Sorrel, to deprive the German 4th Army of the high ground south of Ypres. The ridge commanded the British defences and back areas further north, from which the British intended to conduct the "Northern Operation", to advance to Passchendaele Ridge, then capture the Belgian coast up to the Dutch frontier.

The battle began with the detonation of a series of mines beneath German lines, which created 19 large craters and devastated the German front line defences. This was followed by a creeping barrage 700 yards (640 m) deep, covering the British troops as they secured the ridge, with support from tanks, cavalry patrols and aircraft. The effectiveness of the British mines, barrages and bombardments was improved by advances in artillery survey, flash-spotting and centralised control of artillery from the Second Army headquarters. The Battle of Messines was a prelude to the much larger Third Battle of Ypres campaign.

On 20 September.1917 the 6th Wilts amalgamated with 14 Officers and 232 men of the Wiltshire Yeomanry (by this time dismounted) to become the 6th (Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry) Battalion.

During the last quarter of 1917 the 6th Battalion saw an enormous amount of action. The Battalion took part in the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge (20 to 25 September 1917), the Battle of Polygon Wood (26 September to 3 October 1917), the Battle of Broodseinde (4 October 1917), the First Battle of Passchendaele - part of the Third Battle of Ypres (12 October 1917) and the Second Battle of Passchendaele (26 October – 10 November 1917).

The 6th Battalion took part in the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge (20 to 25 September 1917). This battle marked a change in British tactics during the Third Battle of Ypres. The first part of the battle had been commanded by General Sir Hubert Gough (Fifth Army). That choice had forced a delay of six weeks while the Fifth Army moved into place, replacing General Herbert Plumer’s Second Army. Gough had performed no better than earlier commanders on the Western Front. The Germans had perfected defence in depth. Their front lines were lightly defended. Behind the front line scattered German strong points disrupted any Allied advance. Once the British or French attackers were disorganised, the Germans would launch a counterattack with specially trained divisions kept out of range of Allied artillery. A series of Allied attacks on the Western Front had penetrated the German front line but failed to get past the second.

In the aftermath of the earlier failures at Ypres, Plumer suggested an alternative plan – his “bite and hold” strategy. This was designed to use the German plan against them. The British would pick a small part of the front line, hit it with a heavy bombardment and then attack in strength. The advancing troops would stop once they had penetrated 1,500 yards into the German lines. At this point they would have overrun the German front line and perhaps some of the strong points behind the lines. The attacking troops would then stop and dig in. When the German counterattack was launched, instead of finding a mass of exhausted and disorganised men at the limit of the Allied advance, they would find a well organised defensive line.

Plumer was given permission to try his new plan, and three weeks to prepare. His men received detailed training. The battle began with a creeping barrage 1,000 yards deep, which protected the attacking infantry. The British attacked with four divisions – from north to south the 2nd Australian, 1st Australian, 23rd and 41st Divisions.

The attack was a great success. The majority of Plumer’s objectives were captured on the first day of the attack, only the 41st Division needed to follow up on the following day. German counterattacks were repulsed the first and second days of the attack.

The Battle of Broodseinde, in which the 6th Wilts played a part, was a large operation, involving twelve divisions attacking simultaneously along a 10 km front. It was fought on 4 October 1917 near Ypres in Flanders, at the east end of the Gheluvelt plateau, by the British Second and Fifth armies and the German 4th Army. The battle was the most successful Allied attack of the Battle of Passchendaele. Using "bite-and-hold" tactics, with objectives limited to what could be held against German counter-attacks, the British devastated the German defence, which prompted a crisis among the German commanders and caused a severe loss of morale in the German 4th Army. Both sides were planning an attack on 4 October. When the British bombardment began, it caught a number of German units out in the open preparing for their own attack. The British attack contained divisions from Britain, New Zealand and Australia. As at Menin Road Ridge and Polygon Wood, the British attack achieved its main objectives and then halted to dig in. Although Broodseinde is often described as small scale battle, the casualty figures demonstrate the real scale of the fighting. The Germans suffered 10,000 casualties and lost 5,000 prisoners. On the Allied side the Australians suffered 6,432 casualties, the New Zealanders 892 and the British 300. The battle was recorded as a “black day” in the official German history of war.

The Battle of Poelcappelle (9 October 1917) marked the end of the string of highly successful British attacks in late September and early October 1917, during the Third Battle of Ypres. Only the supporting attack in the north achieved a substantial advance. On the main front the German defences withstood the limited amount of artillery fire managed by the British after the attack of 4 October. The ground along the main ridges had been severely damaged by shelling and rapidly deteriorated in the rains, which began again on 3 October, which in some areas turned the ground into a swamp. Dreadful ground conditions had more effect on the British, who needed to move large amounts of artillery and ammunition to support the next attack. The battle was a defensive success for the German army, although costly to both sides.

The First Battle of Passchendaele took place on 12 October 1917 in the Ypres Salient of the Western Front, west of Passchendaele village, during the Third Battle of Ypres in World War I. The Allied plan was to capture Passchendaele village. This was based on the incorrect assumption that during the Battle of Poelcappelle, three days previous, the attacking troops had captured the first objective line. In fact, the Allied front line near Passchendaele had hardly changed and the true position of the Allied front line, meant that the planned advance of 1,500 yards (1,400 m) was actually 2,000–2,500 yards (1,800–2,300 m). The assault was directly south of the inter-army boundary between the British Fifth and Second Armies and consequently pitted a collection of formations from both armies against the German Fourth Army. Despite advances on the northern front of the battlefield, the German's retained control of the high ground on Passchendaele Ridge and consequently the attack failed in attaining its principal objective. Although the battle was costly to both sides, the battle was considered a German defensive success. Further British attacks were postponed until the weather improved and communications behind the front had been restored.

After just a couple of weeks respite, the 6th Battalion next took part in the Second Battle of Passchendaele (26 October – 10 November 1917), a phase of the Third Battle of Ypres. The battle took place in the Ypres Salient area of the Western Front, in and around the Belgian town of Passchendaele.

At the beginning of 1918 Frank married Amy Louise Curtis (b1894) at Yeovil. Amy, a general domestic servant, lived and worked in Maiden Bradley, Wiltshire.

In 1918 the 6th Wilts were in action in the Battle of St Quentin (21-23 March 1918) and the First Battle of Bapaume (24-25 March 1918), both were phases of the First Battles of the Somme 1918.

The Battle of St Quentin began the German's Spring Offensive on 21 March 1918. It was launched from the Hindenburg Line, in the vicinity of Saint-Quentin, France. Its goal was to break through the Allied lines and advance in a north-westerly direction to seize the Channel ports, which supplied the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and to drive the BEF into the sea. Two days later General Ludendorff, the Chief of the German General Staff, changed his plan and pushed for an offensive due west, along the whole of the British front north of the River Somme. This was designed to separate the French and British Armies and crush the British forces by pushing them into the sea. The offensive ended at Villers-Bretonneux, to the east of the Allied communications centre at Amiens, where the Allies managed to halt the German advance; the German Armies had suffered many casualties and were unable to maintain supplies to the advancing troops. Much of the ground fought over was the wilderness left by the Battle of the Somme in 1916. The action was therefore officially named by the British Battles Nomenclature Committee as The First Battles of the Somme, 1918.

The following day the battalion was involved in the First Battle of Bapaume. In the late evening of 24 March, after enduring unceasing shelling, Bapaume was evacuated and then occupied by German forces on the following day. After three days the infantry was exhausted and the advance bogged down, as it became increasingly difficult to move artillery and supplies over the Somme battlefield of 1916 and the wasteland of the 1917 German retreat to the Hindenburg Line. On 25th the troops were ordered to withdraw and reorganise. The British Official History, which made a painstaking compilation of casualty statistics, quotes a total of 177,739 men of Britain and the Commonwealth lost as killed, wounded and missing in this battle. Of these, just under 15,000 died. Of the 90,000 quoted as missing, a very large proportion were taken prisoner as the Germans advanced. For the same reason, an unusually high proportion of those who died have no known grave.

The Third Battle of Messines, which took place on 10-11 April, was the first major action the 6th Wilts saw in 1918. On 10 April, the German Fourth Army attacked north of Armentières with four divisions, against the British 19th Division. The Second Army had sent its reserves south to the First Army and the Germans broke through, advancing up to 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) on a 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) front, and capturing Messines. The 25th Division to the south, flanked on both sides, withdrew about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi). By 11 April, the British situation was desperate and it was on this day that Haig issued his famous "backs to the wall" order.

The battalion was almost immediately embroiled in the Battle of Bailleul (13-15 April 1918) when the Germans drove forward in the centre, taking Bailleul, 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) west of Armentières, despite increasing British resistance. Plumer assessed the heavy losses of Second Army and the defeat of his southern flank and ordered his northern flank to withdraw from Passchendaele to Ypres and the Yser Canal.

This was immediately followed by the First Battle of Kemmel (17–19 April 1918). The Kemmelberg is a height commanding the area between Armentières and Ypres. On 17–19 April, the German Fourth Army attacked and was repulsed by the British.

It is likely that Frank Whatley was severely wounded during this last battle. He died of his wounds on 26 April 1916, aged 25. He was interred in Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France, Grave IX.A.22 and his name is inscribed on the War Memorial in the Borough.

As a sidenote, the name HF Whalley was originally inscribed on the War Memorial and repeated when the panels were placed on the Memorial when the original inscriptions became worn. It is almost certain that the original inscription of Whalley was a misspelling the name Whatley.

gallery

Henry Frank

Whatley

1892-1918

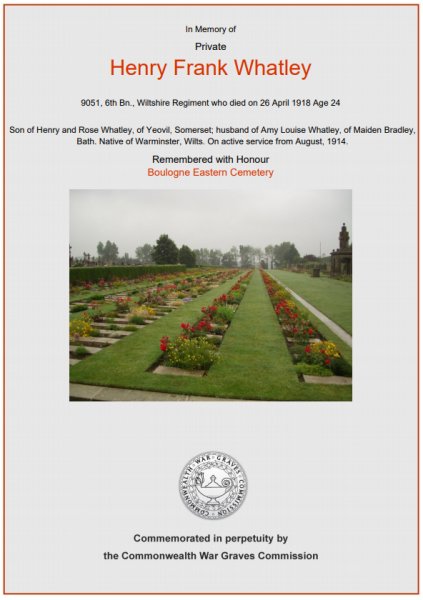

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone (laid flat) for Frank Whatley.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Frank Whatley.