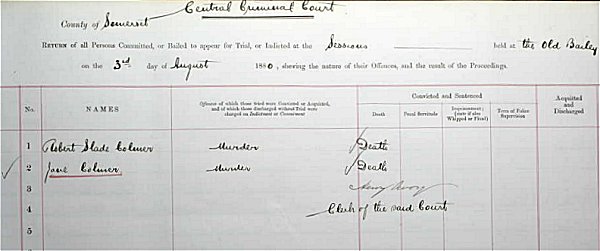

the colmer murder trial

the colmer murder trial

As reported in full in the Western Gazette

ONE OF THE ACCUSED BEFORE THE MAGISTRATES AT YEOVIL

The Western Gazette, Friday 16 April 1880

Robert Slade Colmer was brought up in custody on Thursday at 1 o'clock, before the Mayor (Mr Edward Raymond) and Messrs HB Phelps, James Curtis and John Curtis. Although it was anticipated that proceedings would be merely formal, the court was crowded.

The Deputy Chief Constable, addressing the Bench, said -- I appear by the direction of the Chief Constable to prosecute in this case. The charge against Robert Slade Colmer is one of the wilful murder of Mary Budge, as we allege on 19 March last, and his wife, Jane Colmer, is also charged with the same offence. With respect to Jane Colmer, a medical certificate is produced from Dr Aldridge to the effect that she is unable to appear here today, and what I propose to do is to ask the magistrates to remand both prisoners until Wednesday next. In the meantime, I shall be able to get up the evidence, and I propose to proceed with the case on Wednesday, provided Madame Colmer is in a fit condition to be removed here. The accused are already detained by us under the Coroner's warrant, which I produce, on the charge of wilful murder. This application for remand is in accordance, I believe, with the wishes of the gentleman who defends the accused. I simply ask for remand till Wednesday next.

Mr Trevor Davies -- I appear for both prisoners, and I entirely agree with the application made by the Deputy Chief Constable for remand. I trust the remand will be granted, and that's no evidence will be tendered. Now, for it would be a pity to cut up the evidence.

The Mayor (to the prisoner in the dock) -- We remand you and your wife until Wednesday next, at 11 o'clock, and if Mrs Colmer is not able to be present then, we must further remand you.

The Deputy Chief Constable -- I must ask the magistrates to bind over verbally two witnesses to appear here on Wednesday.

John Haddy Forster, clerk at Stuckey's Bank, Crewkerne, then entered into his recognizance in the sum of £50 to appear as a witness.

Mark Cheney, the father of Ellen Cheney, servant to Madame Colmer, was called in to be bound for the appearance of the girl. He did not understand the proceedings, and said he could not find £50. He was bound over in the sum named.

Prisoner was taken to the Police court and back to the Police station in a closed fly. He shook hands with one of his sons and several other persons in Court, and to did not manifest the least uneasiness.

![]()

THE

CHARGE OF MURDER

AGAINST YEOVIL

HERBALISTS

THE ACCUSED

BEFORE THE

MAGISTRATES

The Western Gazette, Friday 23 April 1880

Not since the trial of the persons implicated in the murder of PC Cox has such a scene of excitement been witnessed in and around the Yeovil Police Court as was seen on Wednesday, when Robert Slade Colmer and Jane Colmer (his wife) were charged before the Mayor (Mr E Raymond), and Messrs James Curtis, John Curtis, HB Phelps, and JC Moore, with the wilful murder of Mary Budge (widow of Mr E Budge, solicitor, of Crewkerne), on March 19. The Marketplace and the approaches to the court were crowded, and as the clock struck eleven, and the doors were opened, there was a rush to secure places, which only careful arrangements, enforced by a strong body of police, could regulate. The persons in the body of the court were of the more respectable class, discretion having been wisely exercised in refusing admission to the rougher element. Many persons must have been disappointed, for the space at the disposal of the public is limited.

The magistrates took their seats punctually, but at quarter-past eleven the prisoners had not appeared, and the Clerk (Mr Batten), sent a constable to seek Superintendent Smith, and explained that the Bench were waiting. The policeman returned with the message that they were "waiting for Mrs Colmer." At 11:30 PS Holwill informed the Mayor that the prisoners would be present in about ten minutes. Mr Watts explained that the delay was due to no fault of the police. The Chief Constable was anxious that the proceedings should not commence till both prisoners were present. Soon afterwards the Chief Constable and the Deputy-Chief Constable entered the court, and the Deputy explained that they had experienced difficulty in getting Mrs Colmer ready. It was nearly a 11:45 when the male prisoner was placed in the dock. He was looking well, and did not appear in the least agitated. After the lapse of ten minutes, the Mayor complained of the delay, and Mr Trevor Davies explained that he could not help it. He had done all he could. Mr Superintendent Smith was in charge of Mrs Colmer. He (Mr Davies) believed that when she did appear, her condition would not allow the case proceeding far. Just before twelve two policeman carried Mrs Colmer into the dock in a chair. She appeared utterly helpless, and was attended in the dock by Mrs Crocker and the two Misses Colmer (her three daughters). Quite prostrate, Mrs Colmer leaned on the shoulder of Mrs Crocker.

The Mayor asked if the prosecution had a certificate that the female prisoner was in a fit condition to be present. The Chief Constable handed in a certificate from Dr Turner, of Sherborne. Mr Watts explained that it was thought best to get a certificate from a medical man not residing in the town. The Mayor thought they ought to have had a certificate of the condition of the woman that morning. This certificate was dated the day before. A doctor ought to have seen her that morning. The Clerk thought the Bench would not be justified in acting upon the certificate produced.

The Mayor -- Looking at the

woman now, I

don't think we

are.

The Chief

Constable -- I

have no desire

to hurry on the

case. If the

magistrates

think we ought

to adjourn for a

week, I have no

objection.

Mr Watts said he

had no objection

to an

examination of

Mrs Colmer now

by a medical

man, to see if

she was in a fit

condition to

remain during

the hearing. He

was quite

willing for any

medical man in

the town, except

her son, to give

an opinion upon

her condition.

Would Mr Davies

allowed Dr

Wybrants, the

coroner (who was

in court), to

examine her and

certify?

Mr Davies -- No.

Mr Watts -- Dr

Wills?

Mr Davis -- No.

Mr Watts -- Under

any

circumstances we

are bound to be

here today.

The Mayor -- Quite

so. As far as I

am concerned, I

should object to

go on with the

examination

unless a

certificate were

produced this

morning. I think

a doctor should

have seen her

one or two hours

before she was

bought here.

(Applause in

Court.)

Mr Watts -- That

was why every

precaution was

taken. Mr Turner

was consulted

for the very

purpose that a

certificate

should be

presented today.

The Mayor -- A

person might be

comparatively

well yesterday,

but very ill

today.

Mr Davis -- I

think it only

fair to state

that Mrs Colmer

has expressed a

wish to be here

today, if

possible. She

was most anxious

to come. I can

vouch for that.

The Mayor -- We

cannot go on in

the presence of

a dead woman.

Mr Davies said

he should like

to make this

further

observation,

that there was

no necessity to

bring Mrs Colmer

there to remand

her. Any

magistrate could

remand her.

Mr Watts said of

course the Chief

Constable had no

desire, one way

or the other. He

suggested that

the case should

be adjourned for

another week.

Mr Moore said that in the presence of the certificate produced and after what Mr Davies had stated, speaking individually, he was not in favour of an adjournment. If a certificate were produced from a medical man who might have seen Mrs Colmer that morning, to the effect that she was fit to be present, he was in favour of the case being proceeded with. After what they had before them, he was not in favour of an adjournment unless another certificate were produced. Mr Davies said he apprehended that, although a medical man might say that Mrs Colmer was not in danger of her life through being brought there, another question would arise - was she in a fit state to instruct him (Mr Davies)? He said she was not. The Clerk said they must find that out. The Chief Constable remarked that the examination would probably last five or six hours. Mr Davies said that in face of what he had seen that morning, and from what he had been told by Mrs Colmer's daughter, he must say that he did not think it would be fair to his client to go on with the examination. The Mayor said the question was - how long should they adjourn for? Mr Davies said he did not think eight days would be too long. It was then decided to remand the case until Wednesday next, at 11 o'clock.

![]()

THE

CHARGE OF MURDER

AGAINST THE

COLMERS

MAGISTERIAL

EXAMINATION

COMMITTAL FOR

TRIAL

The Western Gazette, Friday 30 April 1880

The examination of Robert Slade Colmer and Jane Colmer, for the murder of Mary Budge, widow of Mr Edward Budge, solicitor, of Crewkerne, on 19 March, took place at the Town Hall, Yeovil, on Wednesday. The Mayor and ex-Mayor, and Messrs HB Phelps, John Curtis, and JC Moore took their seats punctually at 11 o'clock. The male prisoner was then placed in the dock, and shortly afterwards Mrs Colmer was carried into the court by two constables. She appeared almost helpless, and was attended by a female in the dock. The court was crowded to suffocation, but still there was a great crush for admission, which had to be stopped by the police. Mr S Watts, of Yeovil, appeared to prosecute, and Mr Trevor Davies, of Sherborne, defended the accused. Deputy-Chief Constable Bigood was present. In reply to the Mayor, Dr Turner, of Sherborne, said Mrs Colmer was in a fit condition to be present today.

Mr Watts said in this case he was instructed by the Treasury to prefer against the prisoners the most serious charge known to the law of England - it was that they, by the use of instruments on the person of Mary Budge, with intent to procure abortion, caused her death. That, in law, amounted to nothing short of wilful murder. The facts were very simple and short, and perhaps it would be as well that he should very briefly run through them, so that the magistrates would be better able to judge of the evidence. He believed that the prisoners were herbalists, the female residing in that town, while the male prisoner came they are only on Fridays. It seems that last month Mrs Budge, who had been a widow about two years, resided at Crewkerne. She got into trouble and he believed she was enciente. On March 17, about 5 o'clock in the afternoon, the deceased drove from Crewkerne to Yeovil in company with a Mr Forster, a lodger at her house, whom he would call as a witness. Mr Davies, interposing, asks that all witnesses should be out of court. Mr Watts replied they are. That precaution has been taken. The Deputy-Chief Constable ordered any witnesses present to leave.

Mr Watts, resuming, said he would prove by Mr Forster that on arriving at Yeovil shortly after 5 o'clock, on March 17, he walked with the deceased from the Choughs Hotel up South Street and across Union Street, where he left her and saw her enter the prisoner's shop (see photograph below). Mr Forster waited for her in Union Street, and she returned in ten minutes or a quarter of an hour. What took place in the shop of course he could not tell, nor the conversation which passed between the deceased and Mr Forster; he would produce no evidence which was not exactly legal. There had been a coroner's enquiry into the lady's death. Much of the evidence they produced was inadmissible here, but while they would leave out much of that evidence, they were in a position to bring before the Bench now very material and important evidence, which the Coroner never had before him.

After the deceased rejoined Mr Forster in Union Street, she went back again to the prisoner's about 6:30, and was absent about two hours. What took place again could not be told. At any rate, at 8:30 she came back to the Choughs and they drove home together to Crewkerne, the deceased being then in perfect health. Up to that time nothing very important was known. Next day, March 18, Mrs Budge wrote a letter to the female prisoner, and it was addressed outside by the witness Forster "Dr Jane Colmer, Middle Street, Yeovil" and posted by him at the Crewkerne Post Office, on the Thursday afternoon. He had given notice to the other side to produce that letter, but did not know whether his friend would do so. The contents of the letter which he asked for were as follows ---

Mr Davies objected to going into the contents of the letter now. They had much better argue the point when Mr Forster produced it. Mr Watts replied, Well, at any rate, a letter was written by the deceased, and sent to the female prisoner. It was addressed by Forster, and posted to Mrs Colmer, next day - March 19. Mrs Budge (deceased) left Crewkerne in perfect health. She was then in the family way. He should prove, by the evidence of the stationmaster at Crewkerne, that she took a ticket for Yeovil. She was seen by the stationmaster at Yeovil to get out. She got into the Mermaid omnibus, and was put down by the conductor near the residence of Mrs Colmer. He should prove by witnesses that she was seen to enter Mrs Colmer's shop about 12:15 o'clock. A short time after that a servant girl, Ellen Cheney, was sent by the female prisoner in search of the male prisoner, who was at that time at his son-in-law's (Mr Crocker) house. The message was to this effect "Tell your master he is wanted; to come as soon as he can." Previous to this, Ellen Cheney had seen the deceased in the sitting room at Mrs Colmer's shop, sitting on the sofa. When the male prisoner left Mr Crocker's house, he followed the witness Cheney up the street. She went into the kitchen by a side door, and the male prisoner went into the shop. What followed? About 3 o'clock this girl (Cheney) where into the kitchen. She heard the male prisoner shout out in a very loud voice "Mrs Colmer! Mrs Colmer! Come, she has fainted!" Mrs Colmer did come. She was then in the shop. She carried the male prisoner a towel, and then unlocked the door that separated the dining room from the kitchen. The servant girl was out of the house all the afternoon running on errands; but what she knew more was this - that about 7 o'clock in the evening the door which he (Mr Watts) told that was previously locked and was now unlocked; and as she (Cheney) passed that door, to go to the Mermaid for the 'bus, she saw the deceased sitting on the sofa, the female prisoner supporting her. She appeared to be very ill, very weak, and very much distressed. Now in this dining room were two windows. One looked into the shop, and the other into the yard. He should prove that on the day in question the blinds of those windows were drawn down. The door leading from the dining room to the kitchen was locked. Over that door were clear glass panels, and paper was put over them. He would prove that about 3 o'clock a person - a perfect stranger - entered the shop. Groans were heard. The female prisoner went to the dining room door and made a noise with it. The screams then ceased.

About 4 o'clock, Mr Godfrey, who lived next door to the prisoner, went into the shop to speak to him about some alterations to the premises; but he was told by the female prisoner that he could not go into the room, as there was some person in there. A little before 8 o'clock in the evening, deceased was seen to get into the Mermaid omnibus and go down the street. He should prove that when the deceased arrived at Crewkerne - where she left in the morning in perfect health - she was in a terrible state. She expired the next afternoon. What was the cause of her death? It would be clearly proved in fact, to use the words of the doctor, the cause of death was "exhaustion, arising from loss of blood; that the place or organ whence the haemorrhage proceeded was the uterus; and that the cause of such haemorrhage was injury to the internal structure of the uterus by some unnatural and unskillful interference." This was the evidence he should have to adduce.

Now, in this case, he could not call any person who actually saw the act done by the prisoners on the deceased. In all these cases it was difficult to prove cases direct, for this reason - that when a person attempted to procure abortion, they might rest assured that the act would be done when no other person was looking on. But what had they? They had something more important than this; they had a chain composed of links, not one of which was missing. They had evidence to show that the woman left home in the morning in perfect health; they should prove that she went into Colmer's shop; that the blinds were drawn down; that the door was locked; that deceased was at the house that afternoon; that she was seen at 7 o'clock by the servant girl; and how she saying? In a very weak and delicate state. There was another point in this case - that on the day in question the family, who invariably dined in the dining room, did not take their meals in that room; the dinner was laid in the kitchen. These were the principal facts which he should have to lay before them.

Now they knew very well that the prisoners were not on their trial today. It was not for the Bench to say whether the prisoners were or were not guilty of the charge made against them; all they had to do was to satisfy themselves that the evidence was sufficient to put the prisoners on their trial; that there was prima facie evidence to show that they were connected with the death of the deceased that a great crime had been committed there could be no doubt. The grand question was - who caused the death? The magistrates were not asked to state who caused the death; all he (Mr Watts) asked them to do was to say whether the evidence he should produce before them was not sufficiently strong to justify them in committing them for trial at the Assizes. Of course, if they could produce evidence on another occasion, the better it would be for them; the responsibility of returning a verdict would rest with the jury. Mr Watts concluded by remarking that he confidently left the case in the hands of the magistrates.

John Haddy Forster -- in March last I was a clerk in Stuckey's Bank at Crewkerne. I lodged with the deceased, Mary Budge, and had done so since September 1878. On Wednesday, March 17, I accompanied her to Yeovil. I drove her in a pony trap, and we arrived there at about 4:45. She was then very well indeed. I walked through South Street to the top of Union Street, and she went to Madame Colmer's. I saw her go in at the shop door. I saw her ten minutes afterwards in Union Street. We went back to the Choughs, and at 6:30 I went in company of the deceased to Mrs Colmer's. I only went to Union Street with her - left her at the bottom of the street. That is about 50 yards from Mrs Colmer's house. I met deceased again about 8:15 in Union Street by appointment. We went to the Choughs, and then drove home. On the next day - Thursday - deceased wrote a letter to Madame Colmer. I saw that letter, and directed it myself. The address was "Dr Jane Colmer, Middle Street, Yeovil." I posted it myself between four and five o'clock in the afternoon. I read the letter.

Mr Watts asked

for the letter.

Mr Davies -- I

can't produce

it, because we

never received

any such letter

at all. I will

prove it just

now.

Mr Watts -- just

tell the bench

as clearly as

you can what

were the

contents.

Mr Davies told the witness not to answer the question. He objected in toto to any such question, because it at once raise the question of receiving secondary evidence of a document not before them. Perhaps that question of law was so abstruse that the magistrates would find some difficulty in coming to a proper conclusion on it. In the authorities it was perfectly clear that before they could give secondary evidence of an alleged document they must prove first that such a document existed, and go further to prove that it had been recently in the hands of the persons who were expected to produce it. It would be absurd to allow the prosecution to say a man must produce this or that document without any proof that it ever came into his possession. The prisoner denied ever having the document, and it was not sufficient, simply on serving a notice to produce an alleged document, that the prosecution should use the most damning literary evidence to connect the prisoners with the crime of murder. It was laid down that there must be some reasonable evidence that the document came into the hands of a prisoner, but the evidence just given was not prima facie evidence given in a civil action to bring the letter home to the prisoners. Where the Legislature thought such evidence should be sufficient clause was invariably inserted in the statute to that effect. Having quoted from Roscoe's "Law of Criminal Evidence" he again urged that before the prosecution were entitled to proceed with secondary evidence they must reasonably trace the document to the custody of the prisoners. In a crime of this nature the prisoners were asked to produce a document, adverse to them, with not a tittle of evidence that it was ever in their custody. The very gist of the whole thing was that the document should have been reasonably traced to their possession or control, and the notice to produce was not worth the paper it was written on a less most cogent evidence to that effect was given in such a case. Until that had been done, his friend had no right to call on them for a document which, as far as he knew, might be imaginary - it might never have been written, posted, or delivered; it might have been lost in the Post Office or fallen into other hands.

Mr Watts, in reply, said the same rule existed in criminal as in civil cases, and there was no distinction whatever. Mr Davies had talked about the imagination of the witness, but Mr Forster, who was on his oath, swore that the letter was written by the deceased, directed and posted by himself. That theory fell to the ground, because they had the best evidence in the world that the letter was written and posted. He had complied with the rules before producing secondary evidence by raising at least a reasonable presumption that the original was in the hands of the adverse party. The magistrates, after consulting with their clerk, decided against the reception of the letter.

Forster's examination (continued) -- On Friday, March 19, in the morning, about 9 o'clock, I saw the deceased and she appeared to be very well. In consequence of what she said I met her at Crewkerne railway station in the evening. I was at the station before the train arrived, and saw her get out of the carriage. She was then very ill - very different to what she was in the morning. I assisted her out. Miss Edith Budge was at the station. She came by the same train, but not in the same carriage. I accompanied deceased in the omnibus to her house. I assisted her out. I did not see her again that night after she went into the house. I did not see her next morning. I did not see her again. The photograph produced is one of the deceased. Her age was 36 or 37.

Cross-examined

--

I made two

separate

statements to

the Coroner. The

first was on

Tuesday, 30

March.

Q. And your

evidence was

completed and

signed by you?

A. It was not

read over, but I

signed it. I

made a further

statement to the

Coroner at the

next inquiry.

Q. On the first

inquiry you were

represented by

Mr Jolliffe?

A. He was there

on my behalf. On

the second

inquiry I

supplemented the

evidence given

at the first

inquiry. Mr

Watts was then

present. That

statement was

given of my own

free will. No

promise of

threat was held

out to me. What

I stated at the

second inquiry

was within my

knowledge when I

gave my first

evidence.

Q. Did you tell

anybody you were

going to give

that second

evidence?

A. I asked Mr

Watts opinion

upon it. Nobody

on behalf of the

police came to

me about it. I

have never

spoken to

anybody

connected with

the police about

it. I and Mr

Watts were the

only persons who

talked about it.

Martha Brook -- I

live in Middle

Street, Yeovil.

I knew the

deceased by

sight. I last

saw her on

Wednesday, 17

March, in Middle

Street, Yeovil.

She came out of

Mrs Colmer's

door - the shop

door. This was

about 5 o'clock

in the

afternoon. My

sister, Mrs

Custard, was

with me.

Deceased spoke

to my sister.

Q. What did she

say?

A. She asked her

not to tell.

Mr Davies -- Oh,

no, no. I was

hardly expecting

that. (Question

not repeated).

Witness

(continuing) -- I

saw Mr Forster

that day in

Union Street,

about 5 o'clock.

After deceased

came out of Mrs

Colmer's, I did

not see deceased

in company with

him. Mrs Budge

was dressed in

black.

Cross-examined

--

I saw deceased

come out of the

shop door.

Re-examined -- When Mrs Budge

came out of the

shop door, she

went in the

direction of

Union Street.

Emily Sarah

Custard, wife of

George Custard,

living in

Princes Street,

Yeovil, said -- I

knew the deceased

slightly,

and saw her on

Wednesday, March

17, in Middle

Street, coming

out of the

prisoners shop,

about 4:55 in

the afternoon. I

was with my

sister, the last

witness. I spoke

to the deceased,

and in

consequence of

what she said -

Mr Davies

protested

against this

implied hint of

what was said.

The Lord Chief

Justice had

ruled that a

policeman was

not entitled to

say "from

information

received."

Mr Watts -- But

this witness is

not a policeman.

(Laughter).

Witness

(continuing) -- I

did not have any

conversation

with Miss Edith

Budge in

consequence of

what took place.

When deceased

came out of the

shop door, she

appeared in good

health. She

tried to avoid

me.

Mr Davis -- I

object to that.

Witness -- When

she came out of

the shop door,

she took the

direction of

Union Street.

She was alone.

She met Mr

Forster in Union

Street. He was

standing in the

street. I saw

them meet, and

Forster took

something from

her hand. I

don't know where

they went.

Mr Davies -- I

have no question

to ask you.

Frederick Mackland said -- I am the postmaster in this town. Witness was questioned as to whether, on Wednesday, 27 March, he received or sent off a telegram. He called the attention of the Bench to the 20th Section of the Telegraph Act 1878. The Act was then sent for, and the witness withdrew.

Alfred Ernest Falkner -- I am booking clerk at the Crewkerne railway station. I knew the deceased. On Friday 19th of March, at 11:45, the deceased took a third-class ticket to Yeovil. I gave it her. I did not notice what state of health she was in. She was dressed in black. The photograph produced is that of Mrs Budge. She (deceased) had no other person with her. I next saw her in the evening, on the arrival of the last down train. I don't know what class carriage she arrived in. The ticket was not given up, as the lady appeared ill, and she was allowed to pass. I did not see her get out of the train. When she went through the office, Mr Forster was with her. Deceased look very ill. She could not walk without assistance. Mr Forster helped her. The ticket was given up on Monday. Witness was further questioned respecting the ticket, when Mr Davies objected. He said the ticket was a written document, and notice also being given. Mr Watts did not press the question.

Mr Wills, surgeon, Crewkerne, then entered the Court, and Mr Watts called attention to the fact, but said he did not objected to his being present. Mr Davies said Mr Wills was in rather an invidious position. Mr Moore said he thought Mr Wills ought to leave the court, as other witnesses had done. (Slight applause).

Frederick

Maunder -- I am

the station

master at the

London and SW

Railway Station

at Yeovil. I saw

Mrs Budge on

Friday, March

19, at Yeovil

Junction by the

up-train due at

Yeovil at 12:25.

I afterwards saw

her in the

middle platform

at Yeovil

station. I do

not know where

she went. She

simply crossed the

platform in the

direction of the

town. She wore a

black cloth

mantle, fitting

the figure. She

was in mourning.

I have not seen

her since.

Mr Davies -- I

have nothing to

ask you.

At this point

the Telegraph

Act was

produced, and

legal discussion

took place

respecting the

admission of

some of Mr

Mackland's

evidence. Mr

Davies said that

until the

telegram was

produced nothing

could be said

about it.

Mr Watts -- Was

any telegram

sent from Mrs

Colmer on 17

March?

Mr Mackland -- I

have been

subpoenaed to

produce the

telegrams, and I

do so; but I

think I am

precluded by the

Act from giving

evidence

respecting them.

I will leave it

to the Bench.

The bench

decided to

receive the

telegrams, and

several were

handed in and

examined. Mr

Davies did not

object to their

going in, but

there was no

evidence yet as

to who wrote

them or anything

of the kind.

Mr Watts -- There

are three

distinct

telegrams, one

from Yeovil and

two from

Bristol. We can

prove the

delivery at the

house. My object

is to prove that

the male

prisoner was not

at Yeovil, and

was telegraphed

for.

Ernest Arnold

Durbin,

telegraph

messenger at

Yeovil Post

Office -- On 17

March last I was

at the post

office. I have

no recollection

of delivering a

telegram at Mrs

Colmer's. There

is another

messenger at the

office named

Stephens. My

number is on the

telegram

produced, and

that shows I

took it out.

Mr Watts wished

to explain why

the evidence was

confused.

Mr Davies -- I

object. Go on

with the case.

Why should we

have a speech

about your being

confused? We may

get speeches all

day. (Laughter)

Witness -- I

delivered two of

the messages

(produced) to

some person in

Mrs Colmer's

shop.

The Clerk then

read the two

messages. They

were from "R S

Colmer, 77½

Old

Market Street,

Bristol, to Mrs

Jane Colmer,

Yeovil." The

first was as

follows :-

"Important

business detains

me tonight; Will

come first train

in the morning,

Arriving at

Yeovil at 9

o'clock

certain." The

second ran: "I

have lost the

train. Will come

this afternoon,

if that will do.

If it will not

do, please

Telegraph."

Richard Sweet -- I

am 'bus driver

in the employ of

the proprietor

of the Mermaid,

Yeovil. On

Friday, March

19, I took a

lady from the

12:25 up-train

at Yeovil. I did

not notice how

she was dressed,

and do not know

about what age

she was. She had

no luggage. She

got out of the

'bus opposite

Mrs Colmer's.

Q. Did you get

off the box

before you

stopped?

A. Not before I

stopped, you

know, sir.

(Laughter)

Q. What induced

you to stop just

opposite Mrs

Colmer's?

Mr Davies

objected. Nobody

could know what

was the

inducement.

Mr Watts -- We

can't have model

witnesses any

more than we can

have model

lawyers.

Mr Watts again

put the

question, and Mr

Davies objected.

Mr Watts (to

witness) -- Did

she make any

communication to

you after the

omnibus started?

A. No.

The Mayor -- It

would be curious

to know for what

reason the

omnibus stopped

opposite Mrs

Colmer's.

Mr Davies -- It

might be

curious, but the

evidence must be

elicited in a

legal manner.

Witness

(continuing) -- I

do not know that

I saw the same

person again. I

drove the bus to

the 8:15 train.

Wills was also

in the bus. I

took up a lady

against the

Castle - the

middle part. It

was five or six

yards from the

spot where I put

one down in the

morning. The

reason I stopped

the omnibus in

the evening was

that the lady

hailed me. I did

not observe the

lady until she

called me. I did

not notice how

she was dressed,

as it was dark.

(A photograph

was handed to

the witness, but

he said he did

not recognise

it.)

The Mayor -- Had

the lady a veil

on?

Witness -- I did

not notice.

Cross-examination

continued -- The

lady had no

luggage. I did

not notice

whether she

appeared to be

in good health;

I took no

particular

notice of her.

A plan of

Colmer's

premises were

here produced.

Frederick Cox -- I

am a surveyor

living in

Yeovil. I made

the plan

produced. It is

a correct plan,

so far as it

goes.

Mr Watts

explained that

it was a plan of

the ground

floor; it did

not contain

sections.

At this point, the Court adjourned, the Mayor remarking that, when they returned, the doctor would be able to state whether or not Mrs Colmer would be able to undergo a further examination.

On the court

re-assembling,

Ellen Cheney was

called. She

said -- in March

last I was

servant to Mrs

Colmer. Mr

Colmer did

not live in the

house. He

visited the

house once a

week - on

Fridays. I have

lived with Mrs

Colmer 11

months. I do not

live with her

now. I left her

on Wednesday

week. I left

because my

father would not

allow me to stay

there. I

remember

Wednesday, 17

March. I left on

good terms with

Mrs Colmer. On

17 March, in the

afternoon, I saw

a lady enter the

house. I saw a

lady there about

7 o'clock. I

should know the

lady if I saw

her again.

(Photograph was

handed to the

witness.) That

was the lady I

saw on that day.

I should think

she was about 33

or 34 years of

age. The lady

was in the

backyard with

Mrs Colmer. I

saw her on the

following Friday

in the dining

room at Mrs

Colmer's. This

was about 1

o'clock. She was

sitting on the

sofa. She was

dressed in

mourning, the

same as she was

on the

Wednesday. When

I saw her on the

Friday, she

appeared to be

in good health.

During the

afternoon Mrs

Colmer sent me

down to Mr

Crocker's for

Mr Colmer. The

words used were

"Go and fetch Mr

Colmer; someone

wants to see

him." I went to

Mr Crocker's. Mr

Crocker lives at

the bottom of

Middle Street. I

went and

delivered the

message. Mr

Colmer said he

would come

directly. I

returned to Mrs

Colmer's house.

Mr Colmer came

on behind me.

This was about 2

o'clock. When I

got back to Mrs

Colmer's house,

I went in by the

front door; Mr

Colmer went into

the shop. The

dining room is

behind the shop.

The sofa is

right behind the

door, I did not

see Mr Colmer

afterwards: but

I heard him

call. He was

in the

dining room. He

called for Mrs

Colmer. He said

"Mrs Colmer. Mrs

Colmer." two or

three times;

"Come in, bring

a cloth, she is

fainting!" He

spoke in a loud

voice. Mrs

Colmer came out

of the dining

room into the

kitchen. There

is a door

leading from the

dining room to

the kitchen. I

am sure it was

Mr Colmer's

voice calling

from the dining

room to Mrs

Colmer - I have

no doubt about

it. I was out of

the house a good

deal during that

afternoon; Mrs

Colmer sent me.

I did not see Mr

Colmer until the

evening. I saw

Mrs Colmer again

about 7:30 in

the dining room

when I was going

to order the

Crewkerne train

omnibus, as

young Miss

Colmer had told

me to do.

Mr Watts -- What

were the actual

words Miss

Colmer used?

Mr Davis -- I

object to the

actual words

being given.

Mr Watts -- We

will not go into

it. If you keep

on objecting,

you won't get to

Shaftesbury

tomorrow, you

know.

(Laughter).

Witness

(continued) -- I

then saw Mrs

Budge sitting on

the dining room

sofa with Mrs

Colmer by her

side. There was

gas in the room,

and I could

distinctly see

them. Mrs Budge,

who was near the

door, looked

very ill. Mrs

Colmer seem to

have her arm

around the waist

of the deceased.

Mrs Budge did

not appear to be

as well then as

she was in the

morning. There

was a marked

change. The door

between the

dining room and

the kitchen was

locked, but

someone unlocked

it, and I then

saw Mrs Colmer,

who came from

the dining room

into the

kitchen, and

went back again.

There is a

window in the

dining room

looking into the

yard, and during

that afternoon

the blind was

drawn down, so

that no person

could look in

from the

kitchen. Even if

the blind was

not down, a

person in the

kitchen could

not see another

sitting on the

dining room

sofa. The window

between the shop

and dining room

had a blind,

which is

generally kept

up. I don't know

how it was then.

Two daughters

live in the

house, and

generally have

meals in the

dining room, but

on this Friday

they dined in

the kitchen.

This did not

occur very often

- only when the

dining room was

engaged. Her

hat and mantle

were on. She is

the same lady I

saw on the

Wednesday

talking with Mrs

Colmer. In the

door between the

kitchen and

dining room

there are two

clear glass

panels on the

top, but in the

afternoon, a

newspaper was

put over it, so

that no one

could see

through at all.

I have known

that done before

when people have

been in the

room, but I

cannot remember

the time. The

patients

generally went

into the dining

room.

Q. On what

occasion have

you seen the

paper over the

glass?

A. When people

have been in the

room. But I

can't tell when.

Mr Whitby -- When

has she seen the

paper over the

window?

Witness -- When

people have been

in the room. I

do not know any

particular

occasion.

Examination

continued -- I do

not know what

became of the

towel. I saw a

towel in a basin

of water. This

was a passage

outside the

dining room.

There is coconut

matting in the

dining room. I

did not go into

the dining room

that night. I

went in the next

morning. I did

not observe

anything

particular.

There was some

water or

something wet

on the matting

near the sofa.

When Mr Colmer

comes, he

usually has

dinner in the

dining room. He

did not have any

meals in the

dining room that

day. He slept in

the house and

went away next

morning. I left

Mrs Colmer on

good terms.

Colmer here

whispered

something to his

advocate.

Mr Whitby --

Cheney, can you

give the exact

words made use

of when you

ordered the

'bus?

Mr Davies

objected, and

the question was

not pressed.

Cross-examined

--

I left Mrs

Colmer's since I

gave evidence at

the inquest. I

gave

considerable

evidence then.

Since then I've

been staying

with my father

and mother.

Q. Have the

police been to

see you more

than once since

then?

A. Yes, sir, I

expect they

have,

(laughter).

Q. I believe

since you have

been here you

were taken by

the policeman

into the next

room.

Mr Watts -- She

has been in the

next room with

the other

witnesses.

Mr Davis -- It is

hardly fair

to offer you two

interrupts, Mr

Watts: it is

hardly fair of

the Crown. This

is not a County

Court case: it

is a case of

life or death.

(Slight

applause).

Mr Watts -- You

are irregular.

Mr Davies -- I am

not irregular.

(To the Bench)

--

I think it is

very unwise for

my friend to

quarrel or have

words. If he (Mr

Watts) will

object to the

bench, I dare

say they will

hear him.

Mr Watts -- I do

object to the

Bench.

Cross-examination

continued -- When

the Court

adjourned for

luncheon, I was

taken by a

policeman into

the next room.

Mr Moore -- Are

not all the

witnesses kept

there?

Mr Whitby -- I

have seen that

the police have

done the same in

every case.

Mr Davies did

not impute

anything to the

police. He was

asking for the

facts.

The Mayor -- Have

the police acted

differently to

this girl than

to the other

witnesses?

Mr Davies said

he did not

impute anything.

The Mayor said

he was rather

surprised that

Mr Davies put

the question.

Mr Davies --

Perhaps, sir,

you will not be

so surprised

when you have

heard my

cross-examination.

The Mayor --

Perhaps not.

Cross-examination

continued -- The

police have been

to see me three

or four times

about the

evidence since

the inquiry.

They have not

been a dozen

times. Nobody

else but the

police has been

to see me about

it. A door from

Mrs Colmer's shop

opens into the

street anyone

could see from

the street into

the dining room

if both doors

were open. The

front door of

the shop is into

portions. When

the shutter is

down, the shop

door is open.

There is a

window looking

from the dining

room into the

shop. It is of

clear glass.

Another window

in the dining

room looks into

the yard, and a

window from the

kitchen also

looks into the

yard. They also

partly face the

window in the

dining room.

(Plan of the

premises shown

to the witness).

The Mayor -- I do

not see that you

should say the

window in the

kitchen party

faces the other

window.

Mr Davis -- Don't

you think, sir,

the witness

knows more about

it than we do?

The Mayor said

he thought Mr

Davies was

scarcely drawing

a fair

conclusion. Mr

Davies said the

witness was

there to speak

for herself.

Mr Whitby -- Do

you think she

understands the

meaning of the

question?

Mr Davis -- I'm

not supposed to

know what the

witness means. I

think she is

knowing enough

to know the

meaning of the

word "face".

The Mayor -- I say

they are not

positively

facing. You may

be looking out

of the window,

but you cannot

be facing the

window.

Mr

Davies -- It is a

matter of

opinion. My

opinion will be

at variance with

that of your

Worships.

Cross-examination

continued:

Q. Doesn't the

window the

dining room

partly face

those in the

kitchen?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. If you stand

at the windows

of the kitchen

can you not see

into the dining

room?

A. Some part of

it. If persons

were standing

against the

fireplace in the

dining room they

could be seen

from the kitchen

windows.

Q. If anyone

were standing at

the kitchen

window could

they see the

sofa?

A. No, sir.

Q. Have you

tried it?

A. No; but I

know you could

not see it. You

could not see a

paper on the

sofa because of

the table. You

could see part

of the sofa if

the table was

away.

Q. If I held a

paper above the

sofa, could you

see it from the

kitchen window?

A. Yes.

A discussion took place between the solicitors as to the evidence, and Mr Davies said the Crown ought to be impartial.

Mr Davies, to

Witness -- What

makes you say

such a lot more

now than you did

before the

Coroner?

A. Because I

remember things

better.

Q. Do you

recollect things

better two years

after than at

the time they

took place?

A. Yes.

(Laughter).

Mr Davies -- You

wish us to

believe that, do

you?

A. Yes.

(Laughter).

Cross-examination

(continued) -- I

saw the lady in

the dining room;

I went in there

for some

purpose. I was

only in their

minute.

Q. Had the lady

got a hat and

veil on?

A. Yes.

Q. When did you

see her next?

A. Not until the

evening.

Q. Now what made

you tell the

Coroner that you

didn't see her

after 1 o'clock?

A. I did not

remember.

Q. You were

asked more than

once whether you

saw her more

than once, and

each day you

said you had not

seen her more

than once?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you see

the lady more

than once? Are

you going to

think any more

about it? Will

you pledge

yourself that

you didn't see

her more than

twice?

A. I did not see

her more than

twice. About 2

o'clock I was

sent on a

message by Mrs

Colmer. I

fetched Mr

Colmer.

Q. How long was

it after you saw

the lady? Was it

before you was

sent for Mr

Colmer?

A. About three

quarters of an

hour.

Q. During that

time you, I

suppose, were

about in many

places?

A. Yes.

Q. And for all

you know when

you went for Mr

Colmer, the lady

might have gone

out?

A. Yes.

Q. And I may

take it further

that when you

came back with

Mr Colmer the

lady might have

left the room

and there might

have been

someone else

there?

A. Yes.

Q. I believe you

never saw Mr

Colmer in

the dining room?

A. No.

Q. You never saw

Mr Colmer and

this lady

together in the

dining room?

A. No.

Q. Do you

remember my

asking you this

"Can you swear

of your own

knowledge that

you saw her with

the lady of that

day?"

A. I do not

remember what I

said.

Q. Do you

remember my

asking you

whether you saw

Mrs Colmer with

the lady at all

that day?

A. I do not

remember.

Q. You now say

you saw Madame

Colmer with her

arm around the

lady's waist?

A. Yes.

Q. Is that a

common

occurrence?

A. No.

Q. You say now

that when you

first saw the

lady, at 1

o'clock, she did

not appear ill?

A. Yes.

Q. Did she look

a little pale?

A. No.

Mr Watts -- She

did not say at

Crewkerne that

deceased looked

pale.

Mr Davies -- I say

she did.

Mr Davies -- On

this Friday do

you know if it

was big

market-day in

Yeovil?

A. No.

Q. I take it

that Mrs Colmer

has a good many

patients on

market-days?

A. Yes.

Q. Mrs Colmer

only has

patients in the

dining room?

A. Yes.

Q. And it is not

an uncommon

occurrence for

them to dine in

the kitchen?

A. No.

Q. If you stood

at the passage

door could you

put your hand

upon the dining

room window?

A. Yes.

Q. If you open

the passage door

and got a foot

or two into the

yard you could

see nearly all

over the dining

room, and could

see the sofa?

A. Yes.

Q. There are two

doors to the

dining room, one

from the dining

room to the shop

and the other

from the dining

room to the

kitchen?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you tell

the Coroner

that?

A. No.

Q. How do you

know it was

locked?

A. I heard Mrs

Colmer unlock

it.

Q. Did you see

her unlock it?

A. No.

Q. Are your ears

so acute that

you can tell

whether the door

was unlocked or

only opened?

A. Yes; I could

tell it was

unlocked.

Q. Have you ever

seen a key in

the door?

A. Yes.

Q. Within the

last month?

A. Yes.

Q. Would you be

surprised if I

told you that

there has been

no key to the

door for a

twelvemonth?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You won't say

there is a bolt

on the door?

A. No.

Q. You have told

us that Mr

Colmer slept in

the house that

night?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You are sure?

A. Yes.

Q. Would you be

surprised if I

were to tell you

that he slept at

Weymouth that

night?

A. Yes.

Q. You pledge

your oath on

that?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you hear

Mr Colmer say

that evening

that he had to

go to attend the

Weymouth County

Court the next

day?

A. Yes.

Q. You say that

is, during the

afternoon you

were "in and

out"?

A. Yes.

Q. And during

part of that

afternoon you

heard Mr Colmer

ask for a cloth?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you

remember what

you told the

Coroner?

A. No.

Q. What did he

say?

A. "Mrs Colmer,

Mrs Colmer, come

in; she has

fainted!"

Q. You didn't

say those words

before the

Coroner?

A. No.

Q. When you were

before the

Coroner you said

you simply heard

Mr Colmer call

for a cloth?

A. Yes.

Q. You also, I

believe, before

the Coroner

denied having

used these words

to Mrs Knight,

"He was in the

room for two

hours, and I

heard him say to

Mrs Colmer she

has gone off,

bring some

water?"

A. Yes.

Q. Madame Colmer

took the cloth

from the room.

How do you know

that?

A. She must have

done so.

Mr Davies -- Never

mind what you

thought.

Q. The only

reason for your

saying that

Madame Colmer

fetched the

cloth was

because you've

found it in the

water the next

morning?

A. Yes.

Q. When Mr

Colmer called

for the cloth

you don't know

who was in the

room?

A. No.

Q. My friend has

asked you

whether you saw

anything

particular in

the room. You

told the

Coroner, I

think, that you

did not. I

suppose I may

take it that a

little water was

anything

particular?

A. No.

Q. Now you have

been shown a

photograph here

today. I think

the same

photograph was

showing you

before the

Coroner?

A. Yes.

Q. I believe

when you were

asked before the

Coroner if you

recognised the

photograph you

said you did

not?

Mr Watts -- I beg

your pardon.

Mr Davies -- Then

we will look at

our papers.

Mr Watts -- I have

the depositions

here. She said

"The photograph

produced is very

much like the

lady." (This was

a photograph of

the deceased.)

Q. You didn't

state before the

Coroner, as you

do now, that it

was the lady?

A. No.

Q. Was the lady

dressed in

black?

A. I cannot say

how she was

dressed; I only

had a glimpse of

her as I passed

the door, and

did not notice.

Q. Mrs Colmer

has not, I

think, been very

well for some

time before this

enquiry. Sits a

good deal on the

sofa?

A. Yes.

Q. Are you

prepared to

swear

positively, from

that glimpse,

that it was not

Mrs Colmer's

daughter you

saw?

A. It was not

Miss Colmer.

Re--examined --

The police

sergeant served

me with two

summonses to

attend this

court as a

witness. Sgt

Holwill took me

to Crewkerne

before the

Coroner; and

once before this

I was here as a

witness. On

neither of these

occasions did

the police say

anything to me

about my

evidence. I have

seen Mr Davies

once. He try to

get what he

could out of me.

Q. He called on

you?

Mr Davies --

Called!

Mr Watts -- He

interviewed you?

Witness -- He saw

me.

Mr Watts -- Mr

Davies has said

something to you

about your

saying more now

than when before

the Coroner. How

was it that you

did not say more

before the

Coroner?

Witness --

Because Miss

Colmer told

me....

Mr Davies

objected to any

conversation

between the

witness and Miss

Colmer. It could

only be elicited

on

cross-examination.

It could not

arise out of

re-examination.

Mr Watts -- For

once my friend

has been caught

in his own trap.

This arises out

of his own

cross-examination,

and I'm prepared

to to stake my

reputation upon

the point.

Mr Davies -- I

should not do

that.

The advocates

quoted in favour

of their

contentions.

The Bench

decided not to

allow the

question to be

put to the

witness in the

form proposed by

Mr Watts.

Re-examination

continued -- I was

asked before the

Coroner whether

I saw the lady

at Mrs Colmer's

on the

Wednesday. The

blind was down

on Friday

afternoon, and I

could not have

seen the sofa

through the

window if I had

wished to. Mrs

Colmer's arm was

round the lady.

Albert Edward Tanner, of Northover, Ilchester, said -- On Friday, March 19, I was in Yeovil about 2:30 or 3 o'clock in the afternoon, and I saw Mrs Colmer at her shop where I went to buy part of a pipe, and stood at the left-hand counter. A noise in the inner room attracted my attention. Someone called very loudly "Mrs Colmer" in a distressing manner and almost screaming. Mrs Colmer and immediately left me, tried the door, and, finding it fastened, kicked at it, and then came back to serve me.

Walter Fowler, hatter, of Middle Street, Yeovil, directly opposite the prisoner's shop said -- On March 19, I was in my shop and saw the omnibus stop at Colmer's door. A lady dressed in mourning got out, and entered the shop. She was wearing a veil over her face and I saw her speak to Mrs Colmer at the counter.

John Membury,

hairdresser, of

Middle Street,

two doors below

Madame Colmer's

said -- On the

evening of March

19 I was at my

shop door and

saw the Mermaid

omnibus stop at

the prisoner's

side door, and a

lady dressed in

black got into

the vehicle from

the pavement. I

did not see her

come from the

house. She wore

a feather in her

hat or bonnet.

By Mr Davies --

This was about 8

o'clock. Sweet

was driving, and

the omnibus was

20 or 30 yards

away from me. If

Sweet has said

he stopped 5

yards away from

the side door he

is not quite

right.

William Godfrey,

ironmonger,

living next door

to Madame

Colmer, said --

On

March 19 I saw

Mr Colmer a

little before

three in the

afternoon. He

came into my

shop to complain

about some

alterations at

the back of my

premises and

that a grate had

been knocked

about. At 4:30 I

went into

Colmer's shop

and saw the

female prisoner.

Mrs Colmer said

she had someone

in the room then

and that we

could not go in.

By Mr Davies --

Colmer

complained that

I was

encroaching on

his premises at

the back and

said my workmen

damaged his

grate. He did

not say he had

been telegraphed

for to Bristol,

by Mrs Colmer,

because I was

pulling the

place about, and

encroaching on

his premises. I

won't swear

whether the work

was begun

Wednesday or

Thursday. I saw

Colmer again at

4 o'clock in the

garden, but did

not speak to

him.

Re-examined -- Mrs

Colmer did not

complain to me

about the

repairs on

Wednesday or

Thursday.

George Wills, dairy man, of Combe Farm, Crewkerne, said -- On Friday, March 19, I was at Yeovil, and returned by the last train to Crewkerne, being driven in the Mermaid omnibus by Sweet. The vehicle stopped near the Castle in Middle Street, next to Colmer's house, and a lady got in. She was pale, dressed in mourning, and aged about 25. Being shown the photograph, witness said that was the party, only she was paler then, and appeared poorly. She got out of the 'bus at the station, but I saw her again at Crewkerne, where she rode in the 'bus with Mr Forster and another lady. The omnibus stopped at the back of the market house and Mrs Budge got out near her own house.

Edith Cuming -- I live at Gillingham. On Friday 19th of March, I was at Yeovil. I saw the deceased at the L & SWR station door at Crewkerne. Mr Forster was with her. She appeared to be very ill. Before this her health was very good indeed. I had had no intimation of her illness. Mr Forster, Mr Wills, and deceased got into the omnibus. Deceased got out at her own house, near the market house. Deceased was dressed in mourning. She wore a hat. (Photograph handed to the witness). That photograph is a likeness of the deceased.

Elizabeth Herriman -- I live at Crewkerne. Deceased appeared to be as well as usual on the morning of Friday 19 March. Deceased left home that morning by the 11 o'clock train. She came back by the 9 o'clock train that night. She was very poorly indeed. She brought a bottle and some white powder with her. The bottle was filled up with sherry, by direction of the deceased. She went to bed as soon as she returned. I next saw her the following morning at 8 o'clock. She then appeared to be in a great deal of pain. I thought it was her bowels. She spoke, but made no noise. She did not scream out until she was seized with death. She waved her hands. I thought she was faint. I sent for Dr Wills after she screamed. It was proposed to send for a doctor before, but deceased would not allow it. She died at a 5:45.

Annie Elizabeth Budge -- I am daughter of the deceased. On 19 March last she was in good health, mother had breakfast with us, I did not see her after the morning until she came home, at 9:30. She brought home a bottle with her. She could not go to bed without assistance. I slept with mamma that night. She complained of being in pain. I don't think she slept much that night.

Eliza Barrett -- I am a widow, and live at Crewkerne. I knew deceased. I saw her on Saturday 20 March. I saw her clothes. (Witness described the state in which she found the clothes).

Elizabeth Taylor -- I was called in about an hour after deceased died. (Witness gave particulars as to the state of the clothing and the condition of the deceased.)

Dr Wills, of

Crewkerne, was

called, and gave

evidence exactly

similar to that

tendered before

the Coroner. It

was to the

effect that the

cause of death

was exhaustion,

arising from

loss of blood;

that the place

or organ whence

the haemorrhage

proceeded was

the uterus; and

that the cause

of such

haemorrhage was

injury to the

internal

structure of the

uterus by some

unnatural and

unskilful

interference.

Mr Davies (to Dr

Wills) -- I

propose to leave

your

cross-examination

to abler hands

than my own.

Sgt Holwill -- I

am a police

sergeant

stationed at

Yeovil. I found

the instrument

produced in a

drawer in Mrs

Colmer's room,

on 13 April.

Cross-examined

--

Mrs Colmer has a

son living in

the town who was

duly qualified.

He might have

lived in this

house before he

was duly

qualified. I

have not heard

that there is a

son now living

in the house who

is duly

qualified. I

have not asked

to whom the

instrument

belongs.

The instrument

was handed to Dr

Wills, who, in

reply to the

Mayor, said its

general use was

to examine the

uterus.

Mr Watts said that this was his case.

Mr Davies made no speech nor did he call witnesses.

The Bench retired at 20 minutes to seven, and returned into court five minutes later. Mr Davies having stated that the prisoners reserved their defence.

The Mayor said -- Jane Colmer and Robert Slade Colmer - it is my painful duty, in carrying out the conclusion which the bench have come to all the evidence given, to commit you for trial for wilful murder.

The prisoners were at once removed by the police. Large crowds congregated at the streets - especially outside the Town Hall and near Madame Colmer's residence, and there was considerable excitement. In the evening the office of the Western Gazette was literally besieged by persons who were anxious to obtain copies of the special issue of that paper, containing a report of the proceedings.

On Thursday morning, between eight and nine o'clock, the prisoners were driven from the Police Station to Shepton Mallet Gaol in a closed fly. Madame Colmer appeared to be much better than she has been for some time past. Sgt Holwell and PC Hamblin were in charge of the prisoners.

![]()

THE

ALLEGED MURDER

OF MRS BUDGE

QUEEN'S BENCH

DIVISION

(SITTING IN

BANCO AT

WESTMINSTER)

THURSDAY (Before

the Lord Chief

Justice and Mr

Justice Bowan)

The Western Gazette, Friday 9 July 1880

The Queen v. Robert Slade Colmer and Jane Colmer.

Mr Bullen moved, in the case of the Queen v. Robert Slade Colmer and Jane Colmer, for a rule nisi for a writ of certiorari to bring up a prosecution on the coroner's inquisition for trial at the Central Criminal Court, and also that any indictment or indictments which might be found against the two prisoners, who had been committed on the coroner's inquisition, might also be bought up to be tried at the Central Criminal Court. The two prisoners had been committed for trial for the wilful murder of Mary Budge, a widow, who lived at Crewkerne. It appeared (said Mr Bullen) that in the month of March last Mary Budge went from her home at Crewkerne to Yeovil, where the female prisoner was residing and carrying on the business of herbalist. She was there joined by the male prisoner from Bristol, where he carried on a branch business. Mary Budge underwent an operation in the female prisoner's house, which, according to the evidence, caused her death. It was an operation to procure abortion. She returned home on the same day, and died on 20th of March in the present year, and the two prisoners were committed for trial on 28th April.

The Lord Chief

Justice -- What

had the male

prisoner to do

with it? Was he

a party to the

operation?

Mr Bullen

replied that

according to

what was

alleged, the

operation was

performed by the

husband at the

wife's house.

They were living

apart, he at

Bristol, and she

at Yeovil, and

he was sent for,

and he came to

Yeovil and

performed the

operation which

caused the death

of Mrs Budge.

The application

was made owing

to the prejudice

which prevailed

against the

prisoners, so

that it was not

likely they

would be able to

obtain a fair

trial. They were

committed for

trial at Wells

Assize, and the

chief ground

upon which the

application was

made was that

owing to former

proceedings

against the male

prisoner, he did

not anticipate

that justice

would be done to

him by any jury

in that or the

adjoining

counties. In

1864 he was

tried at Taunton

for a similar

offence, and was

acquitted. There

were 42

affidavits, all

sworn by persons

of Yeovil, but

as they were all

of very much the

same tenor, he

would read only

one. This

affidavit set

forth that it

was believed

among the

inhabitants of

the said county

that Robert

Slade Colmer was

sixteen years

ago guilty of

the manslaughter

of a young girl

by attempting to

procure

abortion, and

that both

prisoners had

since been

obtaining money

by criminal

practices, and

that

consequently,

the inhabitants

were eager for

their

conviction. The

deponent further

said that he had

himself

frequently heard

strong epithets

used and strong

indignation

expressed

against them,

that it would be

expedient to the

ends of justice

that any

indictment or

indictments that

may be found

should be

removed by

certiorari

to the Central

Criminal Court,

and that he

believed they

would not have a

fair trial in

Somersetshire or

any of the

adjoining

counties,

because among an

ordinary panel

twelve men could

not be found

unprejudiced

against them. In

fact, Mr Bullen

went on to say,

the excitement

was so strong,

that (and he

said it with

regret) even the

Coroner, who had

not the accused

before him, but

who went into

the

circumstances of

the death of Mrs

Budge, seemed

almost to have

lost his head,

if he might use

the expression,

because he said

to the jury that

"There was

scarcely a paper

or a railway

station where

they did not see

'Madame Jane

Colmer, curer of

worms' but if

destroyer of

babies was put

it was more

likely to be

true." That was

the language of

the coroner,

addressing his

own jury.

There were several other affidavits, among them that of the prisoner's solicitor, Mr Trevor Davies, Clerk to the Justices of Sherborne. He said that the two prisoners were now in Shepton Mallet Gaol awaiting their trial for the murder of Mary Budge, widow, aged 36, who resided at Crewkerne, and was well-known in and about the locality, having been bought before the public a good deal owing to the sudden death of her husband, a solicitor, two years ago. She was then left with five children, and much sympathy was expressed with her. Jane Colmer had for many years advertised herself as a herbalist and cure of worms, by means of the local newspapers and placards at the railway stations, and the rumour prevailed, and was generally believed in Somersetshire and the adjoining counties, that under the pretence of being a curer of worms she carried on illegal practices for the purpose of procuring abortion: and the Coroner at the inquest, in addition to the words quoted above, said "It is not the first time I have been obliged to investigate a painful case, and been obliged to send the husband for trial for the manslaughter of a young woman."

The Lord Chief

Justice: take

your rule

nisi.

Rule nisi

granted

accordingly.

![]()

CROWN

COURT, Monday

(Before

Lord Chief

Justice

Coleridge)

The Western Gazette, Friday 30 July 1880

.... The other case to which he wished to refer was one which he learnt from the public papers was creating a good deal of excitement: but it was a case which, when they had found a bill against the prisoners, would be removed from the consideration of a jury of Somersetshire, on the ground that Somersetshire jury could not try the case fairly, although he did not know why they should be so. He referred to the case of Robert Slade Colmer and Jane Colmer, who were indicted for the wilful murder of a person called Mary Budge, on 19 March, having so wounded her with instruments for the purpose of procuring abortion that she died.

The circumstances of the case were short and simple, and ought to present them no difficulty. It appeared that Mary Budge was a person of respectable position, a widow, and a young woman, comparatively speaking. She was with child, and it appeared that one of the witnesses in the case, whose name he need not mention, must have had something to do with it, although the direct question had not been put to him. This witness lodged in the house with the deceased, at Crewkerne, and some days before the fatal event he drove the deceased to Yeovil in a trap. He took her to the house of Jane Colmer, who was what was called a herbalist, and sold herbs, some innocuous, and some others of a very different character, and without going into the matter particularly they could easily conceive for what purposes some of those herbs were used. However, in the present case, there was but the slightest and faintest possible evidence that herbs were used improperly on the first occasion, when Jane Colmer alone was concerned. Some days afterwards the deceased went over there again, this time alone and by train. It was proved by several people that she was in perfect health when she started. Several telegrams would be put in which passed between the prisoners about this time, the male prisoner having been in Bristol. He was telegraphed to and asked to come home on the day before the deceased arrived at Jane Colmer's; and there was evidence of a letter which was directed for the deceased by the witness he had before mentioned making the appointment with Jane Colmer to come on the day mentioned. To Yeovil on that day the deceased went, and she was seen to go to the house of Jane Colmer.

The house was one with a parlour behind the shop, the parlour having a window opening into the shop, and also a window opening in the yard behind the parlour. On the day in question both these windows were closed, and a newspaper was placed over the one towards the shop, and the blind of the one towards the yard was drawn down. The deceased went in, and shortly afterwards one of the witnesses - a servant to Mrs Colmer - was sent down to another house to Mr Colmer, who came back with the witness. He went into the parlour. The door was locked, and shortly afterwards Mr Colmer came out. Very shortly after this Mrs Colmer was heard almost screaming, "Pray come, she has fainted." and Mr Colmer went back into the room. Nothing was seen of what took place in the room, but Mrs Colmer came out soon afterwards and went into the kitchen, where she took up two cloths, afterwards going back into the parlour. Nothing more was actually seen of anybody - except Mrs Colmer going out - tilt towards the evening, when Mrs Colmer and the deceased were seen sitting on the sofa together, Mrs Colmer supporting the deceased with her arm round her waist, and the deceased looking extremely ill and very miserable. However, she had strength to get to the station, and to go from Yeovil to Crewkerne. There she was met by the witness previously alluded to, taken across the station and put in an omnibus, and then taken to her own home. Her daughter was very much struck with the terrible alteration in the deceased's appearance. She was taken to her bed, where she was very ill, and a doctor was sent for, and it appeared that he hardly arrived before she died. There was an immediate examination. It is something which the deceased had in a bottle, of which she had partaken, there was found to be a mixture, the principal ingredient of which was sulphate of quinine, which was a perfectly harmless mixture, and had probably been given to her to support her, merely as a medicine.