The Flax Industry

The Flax Industry

in and around Yeovil

For centuries flax had been grown in the fields surrounding Yeovil and was a major local crop. The steady decline of the flax industry received a boost at the time of the Great War since flax was needed for covering the aircraft frames for the nascent Royal Flying Corps.

See also - Bunford Flax Factory and Preston Plucknett Flax Works

The following account is reproduced here courtesy of Richard Sims.

![]()

Flax Growing in

and around

Yeovil

Developments

1909-1920

The 1909

Development Act

was intended to

give financial

assistance to

agriculture and

rural areas. The

cultivation of

flax was one of

the crops

chosen.

Development

Commissioners

were appointed

under the Act to

see if flax

growing could be

made viable

again.

One of the Commissioners visited Job Gould in 1911 seeking his advice on the subject. Consequent to that visit was the setting up of the British Flax and Hemp Growers Society in July 1913. Early that year some 45 acres of flax were sown in the parishes of Bradford Abbas, East Coker, Preston Plucknett, Odcombe and Middle Chinnock; the Yeovil area having been chosen because of its long history of flax growing.

The 45 acres of flax sown yielded a harvest of 103¼ tons of flax straw and 9¾ tons of flax seed. Around the same amount was grown the following year. On harvesting, the crops were bought by the Commission and taken to the Abbey Farm of Thomas Hawkins, at Preston Plucknett, for processing. Heavy wooden rollers were used to press out the flaxseed (linseed) oil before the flax was retted in tanks of warm water, specially built for the purpose. It was decided that to make this practicable, the farmer would simply grow and harvest the flax, with it then being sent to separate processing units, such as at Preston Plucknett.

As the acreage of flax was increased in 1916, there was a need to recruit workers to process it. Advertisements for dressers and hacklers appeared in the local papers and later on in the year another for 20 women to pull the flax. The British Flax and Hemp Growers Society was also considering extending their factory at Abbey Farm, to include a new scutching machine, advertising for workmen for scutching and retting. This resulted in the new factory at Bunford.

To help with the harvesting of the flax, some 60 boys from Bristol Grammar School, many of whom cycled from the city, were brought down to South Petherton, camping there.

The following year the Society was advertising for farmers within ten miles of Yeovil to plant 400 acres of flax, for which they would pay £7 per ton. This needed an increase in the number of people needed to pull the flax. Some 400 women were needed for five weeks of the harvesting. They were paid 30/- per acre with accommodation and food provided by the Women’s Land Service Corps. In the end, over 100 women were lodging at Barwick House courtesy of the Messiter Estate. In addition, 105 soldiers from the Home Service Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment were billeted in the surrounding villages from which they were transported by motor vehicles to the fields. It had been hoped to use a flax pulling machine from Ireland, but a shortage of spare parts prevented that from working. New depots at South Petherton and Lopen had been opened where de-seeding and dew retting would take place before the straw was taken to Abbey Farm for processing further.

With the

uncertainty

caused by the

Russian

Revolution on

the supply of

flax, it was

decided by the

Government to

take over all

flax growing,

offering a fixed

price of 25s to

35s per stone.

The aim was to

increase the

supply of flax

needed for

covering the

aircraft frames

for the newly

emerging Royal

Flying Corps as

well as the

usual shirts,

collars and

cloth. Thus,

from 1 January

1918, the

Preston

Plucknett and

Bunford

factories came

under the

control of the

Board of

Agriculture,

Flax Production

Branch, with

Jesse Crumpler

of North Coker

in command.

South

Somerset Textile

Industry

In 1918 it was

intended that a

further increase

in the amount of

flax grown would

be made and

there were

adverts placed

to recruit

farmers. In the

event, some

3,460 acres of

flax was grown.

To harvest this amount, some 1,000 workers were required. This was a complex task with preparations being completed in June. Weeding of the crop was undertaken by 120 local Boy Scouts and local women. Pulling needed some 2,000 or more women to be taken from Universities and Colleges. 563 were billeted in a tented camp at Barwick Park, 217 at Ilchester, 238 at Lenthay, Sherborne, 110 at Milborne Down, 74 at Gillingham, 514 at Hinton St. George, 268 at Wellington, 228 at South Petherton and four camps in Bridport with 85 in each. In addition, at Dorchester, use was made of 300 German POWs, who also helped in the preparation of the camps.

The pulled flax was taken to be processed at Yeovil, Dorchester, Bridport, Lopen and Taunton. While deseeding took place at Beaminster and West Chinnock.

With the war coming to an end, the long-term future of flax growing came under scrutiny. There was pressure to ensure that it had a business footing in future. The British Flax and Hemp Growers Society were still seeking grants to continue its programme started under the Board of Agriculture. There was a problem of recruitment of seasonal workers and complaints from local farmers that the Society was paying high wages and taking away workers from local farms.

In 1919, with the war over, the growing of flax was seen as a commercial operation, with the recruitment of seasonal flax workers down to the individual farmers. No women’s camps were arranged, with some farmers putting up tents and others providing lodgings on their farms. They also had to advertise for workers through the local labour exchange. With some 4,800 acres of flax being grown, it was expected that between 1,000 and 1,200 workers would be needed. They would be working in gangs and paid £3 10s per acre, based on the normal agriculture wage of 36/6 per week for men and 25/- per week for women. Camping equipment was to be provided but the workforce was expected to provide their own mess facilities, with farmers helping out. In the same year, an agreement was made with the GWR to lay a siding into the factory from the Yeovil-Taunton railway line.

After the

War, the

Ministry

disposed of

these factories

to the private

sector in 1920.

The

Wessex Flax

Factory Ltd.

In March 1920,

the Ministry of

Agriculture

disposed of the

Yeovil area

factories to the

investment

bankers Pinners

Hale, though the

business was

being run by

Messrs A

Mitchelson & Co

Ltd. Wessex Flax

Factories Ltd

was formed to

take over from

Mitchelson. The

new company had

a share capital

of £200,000 made

up of 140,000

preference

shares of £1,

plus 1,130,000

ordinary shares

of 1/- and

70,000 staff

shares of 1/-

while the

Government also

held 30,000 6%

debentures. The

directors were F

Shearman

(Chairman) of

Tiverton, W.

Harvey-Blake of

Norton-sub-Hamden,

T. Selby-Down of

Castle Cary,

Jesse Crumpler

of West Coker

who was the

Managing

Director and

Archibald

Michaelson, the

Chairman of the

Anglo-Continental

Guano Company.

After the

war, flax was

still in short

supply.

Nationally the

industry used

100,000 tons, of

which 80,000

tons came from

Russia, and in

1920 this

shortfall was

estimated to be

90,000 tons.

This led the

company to

advertise for

farmers to grow

flax under

contract,

offering £16 per

ton for straw

and seed and at

the same time

they estimated

the profit on

their ‘Wessex

Crown’ brand of

products would

be £40,000 per

year. At the

shareholders’

meeting in July,

it was revealed

that the cost of

the enterprise

was to be

reduced to

£28,000, in lieu

of £97,000, due

to the

incomplete

nature of the

factories.

South

Somerset Textile

Industry

In 1923 the

company was

forced into

receivership by

the Government,

as debenture

holders, to

protect their

interests.

However, it

caused great

concern with the

National Farmers

Union and the

farmers who were

owed money by

the company.

Meetings of flax

growers were

held in many

places and most

believed that

the company

ought to have

gone into

liquidation,

since they felt

that they would

have had a

greater chance

of getting more

of the money

owed to them.

Eventually, the

growers received

an offer from

the Government,

but this did

involve a

significant loss

to each

producer. As

debenture

holders, the

Government had a

claim on the

freehold of the

factories and

were looking for

a use for at

least some of

them.

Linen

Industry

Research

Association

In 1923 a

conference was

held in London

between the

Department of

Scientific and

Industrial

Research and a

number of other

interested

parties. The

outcome was a

decision to

develop a scheme

for the bulking

of the JWS

pedigree flax

seed, which

currently stood

at 16 tons.

In 1924, with no further progress having been made, the Linen Industry Research Association (LIRA) was asked to undertake the work for the year ending in May 1925. The factories at Bunford, Yeovil and Lopen were leased to them for that period. It was hoped that the factories, which were in a reasonable state of repair, would be able to deal with around 1,300 to 1,500 acres of flax in that time.

Growers in

Somerset were

found and

payments

arranged with

some 192 acres

sown. LIRA found

itself in a

position where

it could not

continue the

process of seed

bulking. It was

considered

essential to

provide a bulk

supply of the

JWS pedigree

flax seed for

future use.

Furthermore, it

was agreed that

the only place

in which this

could take place

was Somerset,

where facilities

for retting and

scutching still

existed. It was

not thought that

private

enterprise would

be able to carry

out the task, a

reference to the

failure of

Wessex Flax

Limited.

Flax

Industry

Development

Society Ltd.

Consequently, a

body was to be

formed to take

over the Bunford

and Lopen

factories, with

a view to them

being in full

production by

1926. This would

allow the bulked

seed to go on

sale to the flax

growing regions.

£40,000 was

needed, £15,000

of which was for

the purchase of

the factories.

The balance

would provide

the working

capital and the

operation was to

be supervised

and assisted by

the Ministry of

Agriculture. The

scheme was also

aimed at

increasing

employment in

the area.

Bunford

currently

employed only 15

hands, whereas

it was hoped to

increase this to

around 80, while

Lopen was

expected to

employ a further

40 people.

As a result, the Flax Industry Development Society Ltd was formed, which was a not-for-profit organisation funded by the Government. At the same time, the Minister of Agriculture was registered as being the freeholder of both Bunford and Lopen factories.

The process

of seed bulking

continued for a

number of years.

However, 1932

saw an end to

the experiment.

The decision to

discontinue

production in

Somerset was the

result of a

significant fall

in flax prices

in the previous

year. The aim of

increasing seed

stock and

providing flax

which would be

economically

viable had been

undermined by

the Russians

selling their

flax at a very

low price.

South

Somerset Textile

Industry

Closure of

Bunford took

place in August

1933 with Lopen

following

shortly

afterwards. In

both places, the

loss of some 50

employees at

each site was

carried out over

a period of

months as the

work ran down.

The last chapter

in this

Government

experiment was

carried out in

the auction

room, with the

sale of the

Bunford and

Lopen factories

in 1934. While

Lopen factory

found a buyer,

it was not until

the mid-1930s

that Bunford was

sold to

Aplin and

Barrett for

use as a

creamery.

Yeovil Flax during the great war

The following five colourised photographs are courtesy of Alan Lawrie. His grandmother, Eunice Hillman (seated on the ground in the third photo below), lived in Weston Super Mare and was waiting to go to university in 1918. She was one of the 2,000 or more women taken from universities and colleges, and is almost certainly one of the 563 that were billeted in a tented camp at Barwick Park, since the photographs were taken by Witcomb & Son of Middle Street.

Photographed in 1918, the tented camp, believed to be at Barwick Park, accommodated 563 women flax workers - eight to a tent.

Food preparation at the camp. It is likely that the two army personnel are soldiers from the Home Service Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment who were billeted in the surrounding villages.

Young women flax workers pose in front of their tent. Unfortunately, the writing on the organisation badges the girls are wearing cannot be read.

|

A young

flax

worker

remembers... These are some of her memories given in an interview in 1984.

In the first days only about six girls were sent home as potential flu victims although at night many of us made up our beds outside the tents as they seemed very crowded. We had no proper camp equipment. We carried our luggage in pilgrim baskets. I don’t know how, but at night cows would get into the field where we slept and we could hear them munching. In those days we had not yet cut our hair and many of the girls with abundant long hair thought that the cows would mistake our hair for grass and eat it while we slept, so we wrapped up our heads in scarves before we lay down. The method of work was this. We lined up at the edge of the field about a yard apart, pulled the width of our arms without moving sideways, and then turned around and laid the bunch of flax neatly behind us. If you picked faster than the girl on your left, you changed places with her and so moved over to the first row where you tried to keep ahead. We worked like maniacs to be the first. The farmer who owned the field brought us tea in a sort of tank on a barrow and we left off for a welcome drink in the enamel mugs that we carried with us at all times. Our rations for lunch were two of the hardest biscuits I have ever seen. You needed to dip them into water or tea to make any impression on them. We had cheese some days and a sort of fish paste sometimes, and I think an apple. We wore breeches but I cannot remember how we got hold of them. Were they donated by male cousins who found them for us? Girls had never worn trousers before. We made ample overalls and smocks and we wore any stockings that we could beg, borrow or steal. I remember one pair I had was brown lace. We never thought of going in bare legs. When the overalls got dirty I sent mine home for Mother to wash, and inside the parcel I put an ample portion of cheese, sometimes dry and grubby, but cheese which they had not seen at home for many a day.

We were

taken to

and from

the

fields

in

lorries,

a jolly

ride

bumping

over the

country

roads,

standing

up and

holding

on. We

were a

welcome

amusement

for the

folk who

lived

around

and in

Yeovil,

and on

Sunday

evenings

they

came out

for a

walk

across

the

footpaths

that

bordered

or

crossed

the

park.

They

came in

hundreds

to see

girls in

breeches,

living

in

tents,

girls

who were

helping

to make

those

aeroplanes

that

zoomed

low over

the

fields

of

Somerset.

I had my

bike

with me

and I

liked to

get on

gate

duty on

my

orderly

day. I

would

ride

across

the

fields

and sit

on my

bike and

read

while

minding

the

gate.

After

six

weeks

the camp

packed

up. I

took

myself

on my

bike to

Butleigh

to visit

my

relatives.

Since

mother

came

from a

Butleigh

family,

my

childhood

had been

well

filled

with

postcards

of

Glastonbury,

the Tor

and

places

like

Frome

and

Castle

Cary. A

few

years

later I

again

visited

my

relatives

in

Butleigh

and so

began a

real

love of

the

country

of my

ancestors

and it

was flax

that

brought

me so

much

happiness.”

|

Marching off to work in the flax fields.

A group of young women flax workers pose for a photograph by Witcomb & Son. Alan's grandmother, Eunice Hillman, is sitting on the ground at the front.

![]()

The following series of colourised photographs of young women working in the flax fields of Yeovil through to the processing of the flax, were taken by Horace Nicholls "on a farm in Yeovil" during the Great War of 1914-1918. These photographs are reproduced here under the terms of the Imperial War Museum's Non-Commercial License.

Pulling flax by hand.

Pulling flax by hand.

Pulling flax.

Pulling flax.

Flax pulled!

Collecting the pulled flax.

Collecting the pulled flax.

Collecting the pulled flax.

Collecting the pulled flax.

Collecting the pulled flax.

Collecting the pulled flax.

Skirting the flax.

Skirting the flax.

Carrying the skirted flax.

Laying out flax for dew ripening

Tying and stacking the flax.

A well-deserved rest.

Loading the flax onto a wagon.

Loading the flax onto a wagon.

Girl workers getting a drink from a pump on their way home.

Girl workers getting a drink from a pump on their way home.

.... and then, back at the Flax Factory

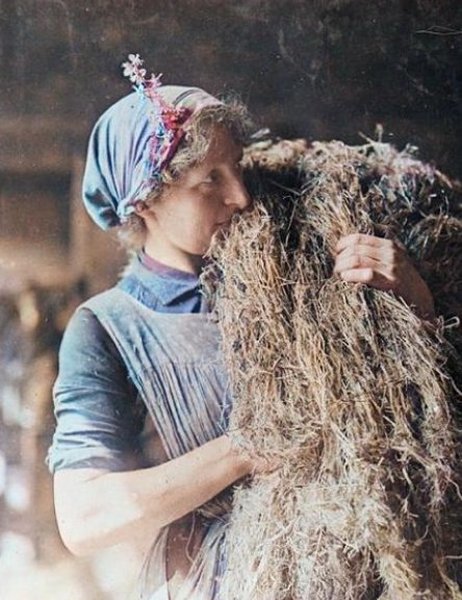

A girl holding a large bundle of flax.

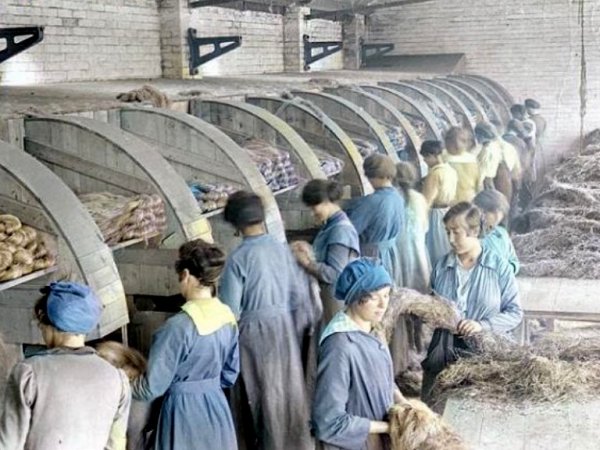

Evening up the lengths of flax for breaking.

Breaking the flax.

Scratching the flax.

A girl with flax ready for spinning.

Weighing finished flax fibre.

Courtesy of Jack

Sweet

Soldiers, probably of the Home Service Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment who were billeted in the surrounding villages and civilian flax pullers, in the Yeovil area during the First World War. Photographed by Witcomb & Son of Yeovil.