the history of yeovil's pubs

PUBS HOME PAGE |

PUBS INTRODUCTION |

PUBS BY NAME |

BEERHOUSES |

pubs Introduction

Everything you need to know about Yeovil's pubs

|

Introduction

I suppose I ought to say it up front - I quite like beer. When I first moved to Yeovil, Somerset in 1973 I had a map on the wall of my office with a red dot for each of the pubs in town I had visited within the first year of moving to Yeovil - all 40 of them. (I also had another map showing over 150 additional pubs that I'd visited in south Somerset and north Dorset during the same period - but that's a story for another day).

In 2012 I spent a pleasant Friday afternoon wandering around some half dozen of Yeovil's finer watering holes with a couple of chums. Not for the first time it cropped up in our conversation about how few pubs there were in Yeovil these days, at least within walking distance of each other - bearing in mind we'd just sauntered the length of Railway Walk from the Royal Marine to the Railway. All three of us have lived and/or worked in Yeovil since the 1970's (and all three of us spend a lot of time in pubs) so we collectively reminisced and tried to count the number of surviving hostelries and came up with a figure of just over 25 - there are, in fact, more like 35 but we had been drinking!

The next day I began to wonder what had happened to all the old pubs I'd known and, indeed if there were any more that I didn't know about. So I began delving into the history of yeovil's pubs - and this section of Yeovil's Virtual Museum is the result. Enjoy. Cheers.

What is a Pub?

A pub, for the purposes of this website, is pretty much anywhere you could have got a pint of ale or cider in Yeovil and consumed it on the premises. However there are, of course, one or two provisos -

- The

establishment

must have

been

licensed to

sell beer,

ale or cider

- thereby

excluding

the various

temperance

establishments

our

Victorian

forbears

were so fond

of.

- The

establishment

had to be

open to the

general

public -

thereby

excluding

private

hotels,

clubs and

institutions

but

including

bars of some

hotels.

- The establishment had to have a name - thereby excluding the majority of simple beerhouses (see below) but including those with names such as the Coach & Horses, Hop Vine Inn, Lamb Inn, Running Horse Inn and the Stags Head Inn. This is a somewhat arbitrary decision on my part (but I had to draw a line somewhere) as it might include pubs that may have been very short lived or were simply pretentious beerhouses like those listed above, but on the other hand dismisses long-established beerhouses like that at Rustywell that was selling cider in the 1870's and continued to do so well into the 1930's - but it still didn't have a name.

Pub, Tavern, Beerhouse - what's the difference?

In pre-industrial England there were basically three types of victualling house which, in declining order of size and status were the inn, the tavern and the alehouse. In common parlance in the recent past, the terms alehouse (later public house or pub), tavern and inn were generally interchangeable, today even more so. For example the establishment in Silver Street, known by one and all simply as 'The Pall', has officially been known at various times as the Pall Inn, the Pall Hotel and the Pall Tavern. However in the past there was a three-fold categorisation recognised in statute and common law with each type of establishment having a particular meaning and each being readily distinguishable.

In early times inns were usually large, fashionable establishments with a license to put up guests as lodgers offering wine, ale, beer and (specially in Somerset) cider, together with quite elaborate food and lodging to well-heeled travellers. The inn was the precursor to today's hotel but inns historically provided not only food and lodging, but also stabling and fodder for the traveller's horse(s).

Coaching inns stabled teams of horses for stagecoaches and mail coaches and replaced tired teams with fresh teams. Typical coaching inns in Yeovil included the Angel, Castle, Mermaid and Three Choughs. Because the passengers of coaches had tended to be the middle or upper classes of society, coaching inns were more likely to be superior establishments that catered for the comforts demanded by these classes. The great heyday of the coaching inns was from the post-Restoration period, climaxing in the 18th and 19th centuries, but by the 1850's their eventual demise was inevitable with the arrival of the railways that changed society with the new concepts of immediate and relatively inexpensive travel.

A

tavern

generally did

not have the

extensive

accommodation

that an inn

could offer,

indeed most

early taverns

did not offer

accommodation at

all. The tavern

was more a place

where people

gathered to

drink alcoholic

beverages and be

served food

although, in

earlier times

especially,

there was little

of the expensive

feasting seen at

inns. The tavern

traditionally

served wine to

its more

prosperous

clientele whilst

the inn served

wine, beer, ale

or cider

although by the

19th century

this distinction

was more than a

little blurred.

Since wine was

far more

expensive than

ale or beer,

taverns tended

to cater to

richer patrons

who could afford

it. They were

usually

restricted to

towns and hugely

outnumbered by

alehouses. While

the numbers of

taverns had

never been great

(nationally they

only accounted

for less than 5%

of licensed

properties), the

heyday of the

old-style tavern

was waning fast

by the end of

the 18th

century.

A

tavern

generally did

not have the

extensive

accommodation

that an inn

could offer,

indeed most

early taverns

did not offer

accommodation at

all. The tavern

was more a place

where people

gathered to

drink alcoholic

beverages and be

served food

although, in

earlier times

especially,

there was little

of the expensive

feasting seen at

inns. The tavern

traditionally

served wine to

its more

prosperous

clientele whilst

the inn served

wine, beer, ale

or cider

although by the

19th century

this distinction

was more than a

little blurred.

Since wine was

far more

expensive than

ale or beer,

taverns tended

to cater to

richer patrons

who could afford

it. They were

usually

restricted to

towns and hugely

outnumbered by

alehouses. While

the numbers of

taverns had

never been great

(nationally they

only accounted

for less than 5%

of licensed

properties), the

heyday of the

old-style tavern

was waning fast

by the end of

the 18th

century.

From the medieval period alehouses were much smaller premises, often ordinary dwellings where the householder served home-brewed ale (at this time ale was essentially un-hopped beer and more simple to brew than beer with hops) or cider. If lodging for travellers was offered, this might be no more than bedding on the floor in the kitchen, or in a barn. The term alehouse was gradually replaced by public house during the 18th century.

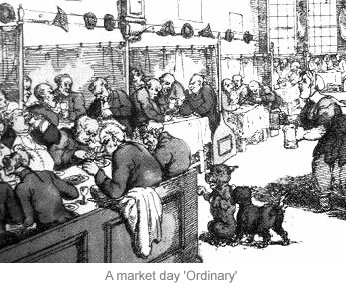

Descended

directly from

the alehouse a

public

house,

informally known

as a pub, was

essentially a

purely drinking

establishment

offering neither

food nor

accommodation.

By the late 19th

century this

distinction was

beginning to

blur as several

public houses

were advertising

"An Ordinary on

Market Days"

where an

Ordinary was,

strictly

speaking, a set

meal taken at a

communal table.

The Butchers

Arms, for

instance,

offered hot beef

dinners with

vegetables for

6d or hot tripe

dinners with

vegetables for

4d. This was

actually a

hangover from

the 18th century

when an Ordinary

was a specific

type of tavern

that would offer

meals to

gentlemen who

could afterwards

indulge in

moderate gaming.

Public houses in

the 19th century

were issued with

licenses by

local

magistrates

under the terms

of the Retail

Brewers Act

1828, and were

subject to

police

inspections at

any time of the

day or night.

Descended

directly from

the alehouse a

public

house,

informally known

as a pub, was

essentially a

purely drinking

establishment

offering neither

food nor

accommodation.

By the late 19th

century this

distinction was

beginning to

blur as several

public houses

were advertising

"An Ordinary on

Market Days"

where an

Ordinary was,

strictly

speaking, a set

meal taken at a

communal table.

The Butchers

Arms, for

instance,

offered hot beef

dinners with

vegetables for

6d or hot tripe

dinners with

vegetables for

4d. This was

actually a

hangover from

the 18th century

when an Ordinary

was a specific

type of tavern

that would offer

meals to

gentlemen who

could afterwards

indulge in

moderate gaming.

Public houses in

the 19th century

were issued with

licenses by

local

magistrates

under the terms

of the Retail

Brewers Act

1828, and were

subject to

police

inspections at

any time of the

day or night.

Public houses, especially those built from around 1850 onwards (and usually built by the breweries), tended to be multi-room establishments with each room designed for its own its own purpose, developing for instance to become the saloon, public bar, snug, games room, dining room, upstairs meetings rooms for societies and associations, the off-license (a product of the 1834 Act) and so on.

A beerhouse was a new, lower tier of drinking establishment permitted to sell alcohol created by the Beerhouse Act 1830 (see above) in which a beerhouse was defined as "where beer is sold to be consumed on the premises". Those running beerhouses had only to buy a license costing two guineas per annum (£2.10). During the 19th century, following the Beerhouse Act 1830, many beerhouses would have been what we call brewpubs today. In other words they brewed their own beer on the premises or, more likely for Yeovil considering it was closely bounded on all sides by extensive orchards, cider. During the middle part of the 19th century an estimated minimum thirty to forty beerhouses were to be found in Yeovil alongside the fifty or sixty 'proper' pubs, inns, taverns, etc. On the other hand, as stated above, many beerhouses became relicensed as public houses after a few years if they didn't disappear altogether.

As with other tradesmen of the time, alehouses, inns and taverns would advertise their business with a sign hanging outside. A pole above the door garlanded with foliage, for instance signified an alehouse. Beginning in the 14th century inns and taverns would often display a pictorial sign by which they could be identified in this illiterate age. From the 16th century many alehouses also began hanging pictorial signs. The tradition, of course, continues for licensed premises.

The Drinking Laws, especially the Beerhouse Act 1830

For a complete guide to the Drinking Laws of England - click here.

The selling and consumption of alcohol was largely unregulated until the Alehouse Act 1552 when alehouses came under the control of local Justices of the Peace who issued licenses and controlled the numbers of licensed premises. Thereafter anyone who wanted to sell ale had to apply for a license at the Quarter Sessions or the Petty Sessions. In addition alehouse keepers had to declare that they would not keep a ‘disorderly house’ and prohibit games of bowls, dice, football and tennis. In the 'Smale Book' of the Clerk of the Peace of 1593-5, is the entry "William Strong and Hugh Plattyn, both of Yeovil, and Joan Pawley of Preston (Plucknett), widow, for selling ale contrary to the statute." Apparently William Strong was discharged but Joan was 'outlawed'. In the same book, a few pages further on we find Hugh Plattyn mentioned again, being brought before the Justices "for an unlicensed and disorderly alehouse."

In 1617 the requirement for licenses was extended to inns. For example in 1617 "John Witticke of Evell, his license taken from him, and to tipple no more." (Ivelchester Sessions, 29,30 April, 1 May 1617 - SRS.23.206).

However, it appears that Yeovil had far too many alehouses than was needed, resulting in a petition by the townspeople as recorded in the Somerset General Sessions held at Taunton in July 1618 "On a petition by the inhabitants of Evell that the number of Alehouses doth far exceed that for which they have occasion; Ordered that there shall be only nine allowed within the burrough and two without, and those to be kept by such persons as by Sir Robert Phelipps and Sir Edward Hext, knts., justices for that limit, shall be thought fit; who have likewise order from this Sessions to suppress the others."

All fared well for many years until, first imported from the Netherlands in the 1690s, gin in various forms began to rival beer as the most popular drink in England. In 1690 William III recklessly dissolved the Distiller's monopoly and allowed anyone to start a distillery by giving ten days notice to the excise. After 1694 gin cost less than beer and this was not the gin we know today but about double the strength! By 1714 there were over two million distilleries in the UK and by 1735 the number was in excess of five million. By 1742 a population one tenth the size of today's was consuming around nineteen million gallons of gin a year - ten times the UK's current annual gin consumption.

During the early 18th century the government permitted this unlicensed gin production and at the same time imposed a heavy duty on all imported spirits. This effectively created a market for home-produced cheap gin and thousands of gin-shops sprang up throughout England, a period known as the Gin Craze. It has been estimated that at any given time during this period a quarter of the population of London, for example, was permanently inebriated.

The 18th century consequently saw a huge growth in the number of drinking establishments, primarily due to the introduction of gin. By 1740, the production of gin had increased to six times that of beer and, because of its very low price, was extremely popular with the poor of which Yeovil had many.

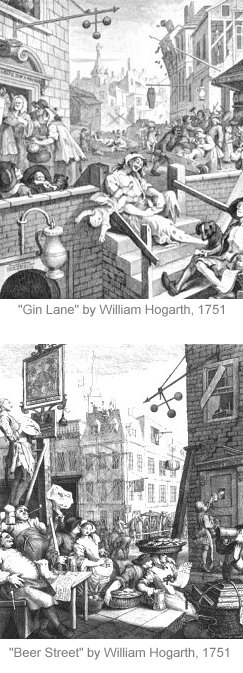

The Sale of

Spirits Act 1750

(commonly known

as the Gin Act

1751) was

enacted in order

to reduce the

consumption of

spirits that was

regarded as one

of the primary

causes of crime,

especially in

larger

conglomerations

such as Bristol

and London. The

drunkenness and

lawlessness

created by gin

was seen to lead

to the ruination

and degradation

of the working

classes. William

Hogarth’s prints

Gin Lane and

Beer Street,

both 1751 and

shown at left,

depict the

perceived evils

of the

consumption of

gin as a

contrast to the

merits of

drinking beer.

Hogarth portrays

the inhabitants

of Gin Lane as

being destroyed

by their

addiction to the

foreign spirit

of gin, while

those who dwell

in Beer Street

are seen as

happy and

healthy,

nourished by the

native English

ale.

The Sale of

Spirits Act 1750

(commonly known

as the Gin Act

1751) was

enacted in order

to reduce the

consumption of

spirits that was

regarded as one

of the primary

causes of crime,

especially in

larger

conglomerations

such as Bristol

and London. The

drunkenness and

lawlessness

created by gin

was seen to lead

to the ruination

and degradation

of the working

classes. William

Hogarth’s prints

Gin Lane and

Beer Street,

both 1751 and

shown at left,

depict the

perceived evils

of the

consumption of

gin as a

contrast to the

merits of

drinking beer.

Hogarth portrays

the inhabitants

of Gin Lane as

being destroyed

by their

addiction to the

foreign spirit

of gin, while

those who dwell

in Beer Street

are seen as

happy and

healthy,

nourished by the

native English

ale.

The licensing system was overhauled in 1828 with a new Alehouses Act that provided a new framework for granting licenses to sell beer, wine and spirits and for regulating inns. But in order to combat the apparent national rise in drunkenness the government enacted the Beerhouse Act 1830 which had been pushed through Parliament by the Duke of Wellington who saw drunkenness as endemic among some sections of the working classes.

The Beerhouse Act 1830 was seen as an attempt to wean the English off spirits, especially gin, by actively liberalising the regulations and increasing competition in brewing and the sale of beer. According to the Act it was considered "expedient for the better supplying the public with Beer in England, to give greater facilities for the sale thereof, than was then afforded by licenses to keepers of Inns, Alehouses, and Victualling Houses."

Under the 1830 Act any householder who paid rates could apply for a license to sell beer, ale, porter, cider and perry and set up a so-called beerhouse, usually in his own home, without recourse to the Licensing Justices. The license would also allow him to brew his own beer, cider, etc. on the premises although only three Yeovil beerhouse keepers were recorded as being a brewer as well as a beerhouse keeper. The license cost a one-off payment of two guineas - £2.10 in today’s money but about £160 in today’s value.

The license did not allow the sale of spirits or fortified wines, and any infringement would result in the beerhouse being closed down and the owner heavily fined. Beerhouses were not permitted to open on Sundays. The beer or cider was usually served in jugs or dispensed directly from tapped wooden barrels on a table. It was not uncommon that, because of the high profits involved, the licensee was able to buy the house next door to live in and turn every room in his beerhouse into drinking rooms for customers. It should, of course, be remembered that the quality of home-brewed beer or cider was always going to be variable at best and many beerhouse owners never intended brewing their own but to buy in from local breweries. The brewers, on the other hand, found the meager amounts sold to beerhouses to be of little overall value and, in the main, the breweries began to direct their energies towards tied houses. One way to combat the rise of the beerhouse was for the breweries to begin building their own pubs which would be tied to the brewery and many pubs starting life in the 1840's and 1850's fell into this category - possibly the Crown Inn, Duke of Wellington, Elephant & Castle, Globe & Crown, Somerset Inn and the Victoria Inn fall into this category.

Nevertheless,

by 1840 there

were 46,000

beerhouses

nationwide and,

because it was

so easy to buy

the license and

its cost was so

low in

comparison to

the huge

potential

profits, the

number of

beerhouses

continued to

rise

dramatically -

to the extent

that nearly

every street had

at least one, if

not more,

beerhouses.

Moreover, many

of Yeovil's

beerhouses were

to develop into

fully-fledged

public houses -

for example the

Albion Inn,

Anchor Inn,

Beehive Inn,

Bricklayers Arms

Inn, Britannia

Inn, Globe &

Crown Inn, Hop

Vine Inn, Market

House Inn and

the Seven Stars

Inn - albeit

with many being

refashioned or

even completely

rebuilt in the

following

decades.

Nevertheless,

by 1840 there

were 46,000

beerhouses

nationwide and,

because it was

so easy to buy

the license and

its cost was so

low in

comparison to

the huge

potential

profits, the

number of

beerhouses

continued to

rise

dramatically -

to the extent

that nearly

every street had

at least one, if

not more,

beerhouses.

Moreover, many

of Yeovil's

beerhouses were

to develop into

fully-fledged

public houses -

for example the

Albion Inn,

Anchor Inn,

Beehive Inn,

Bricklayers Arms

Inn, Britannia

Inn, Globe &

Crown Inn, Hop

Vine Inn, Market

House Inn and

the Seven Stars

Inn - albeit

with many being

refashioned or

even completely

rebuilt in the

following

decades.

Perhaps realising its mistake, the government quickly introduced new licensing laws to curb the expansion of beerhouses. The 1834 Act, for instance, sought to improve the character of beerhouses by raising the license fee to three guineas and required certificates of character for prospective licensees. The new laws eventually made it much harder to obtain a license and by the time of the 1869 Act, the basis of today's licensing laws, effectively prevented new beerhouses being created. Nevertheless, those already in existence were allowed to continue and many did not close for many years – that in Rustywell, for instance, was still operating in the 1930’s and the Royal Marine, typical of many establishments, only obtained a full public house license in 1935.

How many pubs did Yeovil have?

Yeovil has,

apparently,

always had a

large number of

ale houses. In

1618 an order

was made that

only nine be

allowed in the

borough (that is

the town, not

that part of

High Street

today called the

Borough) and two

outside, with

the rest being

'suppressed'.

Yeovil has,

apparently,

always had a

large number of

ale houses. In

1618 an order

was made that

only nine be

allowed in the

borough (that is

the town, not

that part of

High Street

today called the

Borough) and two

outside, with

the rest being

'suppressed'.

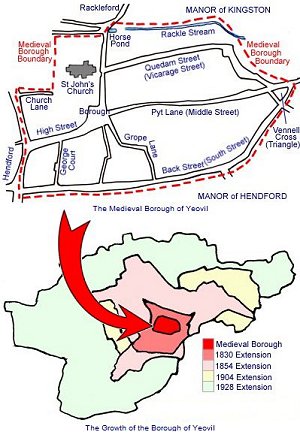

A glance across to the maps at left, however, will show that the Borough of Yeovil at this time was about a hundredth of the size of Yeovil today!

Included within the nine were, most likely, the Angel, the Bell Inn, the White Hart (later renamed the Castle), the Lyon Inn, the Mermaid, the George (in High Street), the Rose and Crown and the Three Cups that was later renamed the George (in Middle Street).

Of course the borough itself at the time was extremely small as seen in this map, comprising little more than a few streets east and south of St John's church (today's High Street, Middle Street and South Street as far as the Triangle and Vicarage Street - now the Quedam shopping centre). By the 19th century, the number of public houses had swelled considerably, but so too had the size of the town's boundaries.

So, bearing in mind the above provisos we end up with a list of 164 named pubs on the Pubs by Name page, although several had more than one name such as the Queen's Arms that became the Royal Oak that became the Hole in the Wall or the White Hart that became the Higher Three Cups that became the Castle Inn. If these multiple-named inns are listed as single establishments the list reduces to 135.

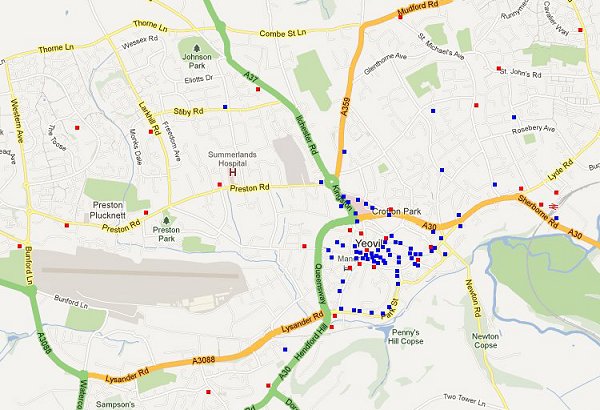

This number does not include the vast majority of beerhouses created by the Beerhouse Act 1830 (see above). The map of Yeovil above has a small blue square indicating the distribution of pubs (not beerhouses) in the town, now no longer with us, and a red square for today's pubs. Indeed quite a few beerhouses evolved into fully licensed public houses, but it isn't always easy to tell them apart in the records.

What is the greatest number of pubs in Yeovil at any one time?

From the early nineteenth century Yeovil developed into one of the country's main centres for leather production and glove making. Documentary sources indicate that by 1840 approximately 75% of the town's population were employed in the leather or gloving industries. Also, as these industries grew, so the population of the town grew - fourfold between 1801 and 1851 (2,774 to 8,739). It remained Yeovil's principal industry throughout the nineteenth century and continued to thrive until the mid-twentieth century. This meant that the town had large numbers of skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled workers and for the majority one of the few pleasures in life would have been a pint or two of cheap ale. The growing number of beerhouses and public houses in the town during the first half of the nineteenth century was really the result of a growing service industry catering for the burgeoning working population of the town.

Also it seems that, after the Beerhouse Act 1830, quite a few glovers and leather workers, as well as other tradesmen, managed to scrape together the required two guineas for a license to open their own beerhouse, often as a sideline to bring in extra money or as a complete change of occupation. It was extremely common for licensees, particularly in smaller establishments such as beerhouses, to work only part-time, combining run a bar with other work. During the day running the pub was left in the hands of his wife and other members of the family. A number of women also ran pubs, often taking over on the death of their husbands or fathers.

Hunt’s Directory of 1850 lists fourteen hotels and inns, forty beer retailers and five wine and spirit merchants in Yeovil. This probably justifies the thought that quite a few public houses started life as beerhouses. Slater’s Directory of 1852 lists two establishments (the Mermaid and the Three Choughs) in the “Inns” category and seventeen further establishments in the “Taverns and Public Houses” section. Additionally twenty nine individuals were listed as “Retailers of Beer” and five as “Wine and Spirits Merchants”. Of course, these directories were, in themselves, incomplete and both miss several establishments.

It's not really easy to distinguish between beerhouses and public houses in the early part of the nineteenth century but in the 1870's there were 63 pubs in Yeovil, 62 in the 1880's, 61 in the 1890's and 58 in both the 1860's and the 1900's. Indeed between the 1860's and the 1960's there were always more than 50 pubs (by my definitions above) in the town. Additionally it has been estimated that, between the 1840's and 1880's, there were probably some 40 licensed (albeit un-named) beerhouses at any one time.

Of course, as mentioned above, during the 19th century the population of Yeovil was growing, from 2.774 in 1801, to 5,590 in 1821, to nearly 13,500 by the 1890's. Nevertheless during the period of the 1850's, '60's, '70's and '80's there was always 1 pub for less than 200 Yeovilians (or 1 pub / beerhouse for about 90 Yeovilians). Today's figure is still a quite impressive 1 pub for approximately every 1,000 Yeovilians. Check out the stats on the Timeline page.

.... and Breweries?

Brewing, of course, is thousands of years old and in the past Yeovil had its fair share of brewers albeit invariably unrecorded. There was one brewing scandal however, recorded in the Session Rolls of 1638 thus - "Petition of Theophilus Collens, portreeve and other inhabitants of the Town and Bourough of Yeovil, against Edward Keynes, gent., concerning some abuses committed by him. He had set up a brew house, and pretending a Patent which was not shown compelled the keepers of inns and alehouses to buy from him till they found his beer to be ill-relished and disliking to towne and country. The town is a great and common road for the most part of the west country men to London; and there is a great weekly market. Ordered that Sir John Stowell, K.B., Sir Henry Berkly, William Walrond. John Harbyn, and James Rosse, Esquires, shall examine the particulars and take such course as they shall think fitt for the relief of the petitioners." (Sessions Roll No LXXVIII, No 56 & 62 - SRS.24.314)

Bearing in

mind that the

Beerhouse Act

1830 permitted

the licensee to

brew his own

beer and/or

cider, the only

premises

actually

recorded as

having their own

brewhouses were

the Mermaid and

the Three

Choughs. However

there were

probably quite a

few

'microbreweries'

in Yeovil during

the 1830's and

1840's although,

as stated above,

only three

beerhouse

keepers, George

Raymond of

Hendford,

William Phelps

of the Sun House

Inn and George

Cole of the

Lamb, were

recorded as

being a brewers

as well as a

beerhouse

keepers.

Bearing in

mind that the

Beerhouse Act

1830 permitted

the licensee to

brew his own

beer and/or

cider, the only

premises

actually

recorded as

having their own

brewhouses were

the Mermaid and

the Three

Choughs. However

there were

probably quite a

few

'microbreweries'

in Yeovil during

the 1830's and

1840's although,

as stated above,

only three

beerhouse

keepers, George

Raymond of

Hendford,

William Phelps

of the Sun House

Inn and George

Cole of the

Lamb, were

recorded as

being a brewers

as well as a

beerhouse

keepers.

The produce must have been variable to say the least and, although the practice of brewing your own undoubtedly carried on, by 1852 Slater’s Directory was listing two “Brewers and Maltsters” – Thomas Cave and Edmund Henning (who rented the George in Middle Street), both of Hendford. Henning's brewery was opposite Hendford House, now the Manor Hotel. It was noted as the 'Old Brewery' in the 1846 Tithe Apportionment suggesting that it pre-dated Cave's brewery.

Also, buying in ale was an attractive proposition for most beerhouse keepers for three very practical reasons. Firstly the brewing process was fairly complicated and also required a capital outlay for equipment. Secondly the quality of the beer could be assured if bought in from a professional brewer. Finally, keeping a beerhouse was, for many, not their prime occupation and their time was therefore at a premium. Many a beerhouse keeper's wife ran the bar during the day while the husband took over in the evening having worked all day.

Joseph Brutton, formerly of Exeter, lived at 7 Princes Street ( 1881 census) with his wife, eight children and five servants. He is recorded as employing 36 men and 3 boys in his brewery (Brutton’s Beers). Brutton’s brewery was located between Princes Street and Clarence Street with a malthouse on the western side of Clarence Street on the land now occupied by Tesco’s car park. A covered footbridge connected the two sites in recent years.

Joseph Brutton’s brewery was established in 1825 in Clarence Street - originally starting life as Kitson and Cave's, subsequently Cave's and was in co-partnership with Thomas Cave by 1854 as Cave and Brutton's, before becoming J Brutton & Sons Ltd. This was to become the largest of Yeovil's breweries, finally being acquired by Charrington & Co (South West) Ltd. The brewery was demolished in 2003 and the site redeveloped as housing. Thanks to Mike Hine for the following memory - "I recall their beer as being nasty, thin, sour piss-water. It could have been that I was too young to appreciate its qualities."

The later Royal Osborne Brewery was in Sherborne Road and also had an aerated water works at the rear of the premises. Its location was next to Osborne House and is currently the site of a car park. Finally it ought to be remembered that breweries outside Yeovil also supplied the town's pubs - the Limington Brewery in Ilchester, Crewkerne United Breweries (with a store at 12 Princes Street, Yeovil), The Dorsetshire Brewery Company in Sherborne and Berryman, Burnell & Co's Charlton Brewery at Shepton Mallet (with offices and stores in Court Ash, Yeovil).

From 2005 until 2022, of course, the Yeovil Ales Brewery produced some really cracking ales.

Where have all the old pubs gone?

Several of

Yeovil's pubs

closed around

the late 1900's

or early 1910's

- the Anchor

Inn, Chough's

Tap, Cow Inn,

Cross Keys,

Dolphin Inn,

Seven Stars Inn,

South Western

Arms and the

Victoria Inn.

The most likely

cause of these

closures was

probably the

Licensing Act

1904.

At this time

there was a

strong

temperance

movement in

England (not

just Yeovil

where there were

at least two

temperance

hotels and the

Temperance Hall)

and a general

feeling that

there were

simply too many

public houses

for the public

good. The

Licensing Act

1904 introduced

a national

scheme whereby

(in theory at

least) a

licensee

surrendering his

license would

receive

compensation.

Under the Act licensing magistrates could refuse to renew a pub’s license if it was considered that the pub was unnecessary to provide for the needs of the public. Compensation could be paid both to the owner of the premises and the licensee although only about 10% went to the licensee. This compensation was paid for by a levy on the licenses granted to other premises. This provision of the 1904 Act was carried forward into the Licensing (Consolidation) Act of 1910.

On a different note, it is worth mentioning that up to the middle of the 20th century the vast majority of Yeovil's licensed premises were what might be classed as town centre pubs simply because the town itself was relatively small (see maps above). Many of these were swept away in the wholesale redevelopment of Yeovil between the 1960's and the 1980's with (in more or less chronological order) the building of Wellington Street flats (Royal Standard, Wellington Inn) development of the Glovers Walk shopping complex (Coronation Hotel, Railway Inn), the widening of Reckleford and Kingston to dual carriageway standard and the building of the new hospital complex (Market Street Inn, Nags Head Inn, Red Lion Inn, White Lion Inn), the building of the Quedam shopping centre (Albion Inn, Anchor Inn, Britannia Inn) the building of Queensway (Victoria Inn, White Lion) and the building of the Tesco store (Crown Inn). Another prime cause of pubs being lost were the ubiquitous road widening schemes (Cross Keys, Dolphin Inn, George Inn, Globe Inn, Golden Lion Inn, Oxford Inn, Rifleman's Arms Inn, Volunteer Inn).

Of course, with the increase in pub closures over the past few years and bending to the pressures of modern economics some former pubs have been converted into flats (Glovers Arms, Nelson Inn, Three Choughs Hotel, White Horse Inn) or demolished and replaced by small blocks of flats or other accommodation (Alexandra Hotel, Somerset Inn, Sun Inn, Westfield Hotel).

On the flip

side, as

Yeovil's

population

expanded, much

new housing was

built on the

edges of the

town leading to

a surge of

building new

'estate' pubs,

especially

during the

1950's (Fleur de

Lys, Green

Dragon, Milford

Inn, Royal

Standard, Sun

Inn, Yellow

Wagtail).

On the flip

side, as

Yeovil's

population

expanded, much

new housing was

built on the

edges of the

town leading to

a surge of

building new

'estate' pubs,

especially

during the

1950's (Fleur de

Lys, Green

Dragon, Milford

Inn, Royal

Standard, Sun

Inn, Yellow

Wagtail).

Many of these are now looking a little 'tired' or have disappeared completely.

More recent additions include Airfield Tavern, Arrow, Beach and Modello.