yeovil at War

William John 'Jack' Bindon

Killed by shrapnel in the Battle of Arleux

William John

Bindon, known as

Jack, was born

in Torquay,

Devon, in 1895.

He was the son

of William Henry

Bindon

(1869-1925), a

printer's

compositor

originally from

Totnes, Devon,

and Ellen

Elizabeth née

Thorne

(1874-1962),

originally from

Stoke sub

Hamdon. The

photograph at

right is of Jack

as shown in the

press at the

time of his

death.

William John

Bindon, known as

Jack, was born

in Torquay,

Devon, in 1895.

He was the son

of William Henry

Bindon

(1869-1925), a

printer's

compositor

originally from

Totnes, Devon,

and Ellen

Elizabeth née

Thorne

(1874-1962),

originally from

Stoke sub

Hamdon. The

photograph at

right is of Jack

as shown in the

press at the

time of his

death.

The

family moved

around quite a

lot; Jack was

born in Torquay,

Devon while his

siblings Cyril

Thorne and Cissie May were

both born in

Southampton,

Hampshire, in

1899 and 1900

respectively,

their next son

Wyndham William

was

born in 1905

at Stoke sub

Hamdon while the

last two daughters Irene

Gwendoline and

Florence Phyllis

were both born

in Preston

Plucknett in

1909 and 1910

respectively.

born in 1905

at Stoke sub

Hamdon while the

last two daughters Irene

Gwendoline and

Florence Phyllis

were both born

in Preston

Plucknett in

1909 and 1910

respectively.

In the 1901 census the family were living in Palmerston Road, Southampton, where William Snr worked as a printer's overseer. By 1911 the family were living at five Preston Grove. William Snr gave his occupation as printer's compositor while Jack listed his occupation as a shop assistant at greengrocer's. In fact he worked in Llewellyn's greengrocery in High Street (first photograph below). The family later moved to 28 Beer Street.

From his Service Number 9610, Jack enlisted in the Somerset Light Infantry of the Regular Army at Yeovil around July 1913. From the battles he is known to have fought in, Jack must have joined the 1st Battalion.

At the outbreak of war in 1914 the 1st Battalion was in Colchester, with 11th Brigade, 4th Division. The Battalion landed at Le Havre, France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on 22 August 1914, in time to fight in the battle of Le Cateau during the retreat from Mons. The 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry remained on the Western Front with 4th Division, throughout the war, suffering 1,315 losses.

Jack Bindon saw four years of almost continual fighting as he took part in all the following battles with the 1st Battalion of the Somersets.

In 1914 the 1st Battalion saw action at the Battle of the Marne, the Battle of the Aisne and at the Battle of Messines.

The First Battle of the Marne, fought from 5 to 12 September 1914, resulted in an Allied victory against the German Army. The battle was the culmination of the German advance into France and pursuit of the Allied armies which followed the Battle of the Frontiers in August, which had reached the outskirts of Paris. The counterattack of six French field armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) along the Marne River forced the German Imperial Army to abandon its push on Paris and retreat north-east, leading to the 'Race to the Sea' and setting the stage for four years of trench warfare on the Western Front. The Battle of the Marne was an immense strategic victory for the Allies, wrecking Germany's bid for a swift victory over France and forcing it into a drawn-out two-front war.

The First Battle of the Aisne was the Allied follow-up offensive against the right wing of the German First and Second Armies as they retreated after the First Battle of the Marne earlier in September 1914. The offensive began on the evening of 13 September, after a hasty pursuit of the Germans. When the Germans turned to face the pursuing Allies on 13 September, they held one of the most formidable positions on the Western Front. Low crops in the unfenced countryside offered no natural concealment to the Allies but deep, narrow paths cut into the escarpment at right angles, exposing any infiltrators to extreme hazard. In dense fog on the night of 13 September, most of the BEF crossed the Aisne on pontoons or partially demolished bridges. Under the thick cover of the foggy night, the BEF advanced up the narrow paths to the plateau. When the mist evaporated under a bright morning sun, they were mercilessly raked by fire from the flank. Those caught in the valley without the fog's protective shroud fared no better. It soon became clear that neither side could budge the other and since neither chose to retreat, the impasse hardened into stalemate that would lock the antagonists into a relatively narrow strip for the next four years.

The Battle of Messines, fought between 12 October and 2 November 1914, was part of the 'Race to the Sea', the series of battles that decided the line of the Western Front. In the aftermath of the first Battle of the Marne, it was decided to move the BEF back north to Flanders, to shorten its supply lines back to the channel ports. The Battle of Messines was the official name for the fighting between the river Douve and the Comines-Ypres canal, but it merged into the battle of Armentières to the south and the first battle of Ypres to the north.

In 1915 the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry fought in the Second Battle of Ypres.

The Second Battle of Ypres, 22 April-25 May 1915, was a rare German offensive on the Western Front during 1915. It was launched with two aims in mind. The first was to distract attention from the movement of German troops to the eastern front in preparation for the campaign that would lead to the victory of Gorlice-Tarnow. The second was to assess the impact of poisoned gas on the western front. Gas had already been used on the eastern front, at Bolimov (3 January 1915), but the tear gas used there had frozen in the extreme cold. At Ypres the Germans used the first lethal gas of the war, chlorine. The gas was to be released from 6,000 cylinders and would rely on the wind to blow it over the allied trenches. This method of delivery controlled the timing of the attack – the prevailing winds on the western front came from the west, so the Germans had to wait for a suitable wind from the east to launch their attack. The line around Ypres was held by French, Canadian and British troops. The attack on 22 April hit the French lines worst and, not surprisingly, the line broke under the impact of this deadly new weapon. The gas created a gap 8,000 yards long in the Allied lines north of Ypres. The success of their gas had surprised the Germans who didn’t have the reserves to quickly exploit the unexpected breakthrough, allowing enough time to plug the gap with newly arrived Canadian troops. During the battle the British, French and Canadians suffered 60,000 casualties, the Germans only 35,000.

Jack was invalided home after the Second Battle of Ypres, suffering from bronchitis. On recovering at Taunton he was transferred to the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry and returned to France with them when they embarked for Le Havre on 10 September 1915. The 8th Battalion was part of 63rd Brigade which, on 8 July 1916 was transferred to 37th Division.

In April 1917 the 8th Battalion took part in the Battle of Arleux. According to the Regimental History of the Somerset Light Infantry "The Battle of Arleux, fought on 28th and 29th of April, the 8th Somersets of the 37th Division again taking part in the operations, though the only Battalion of the regiment to do so. The front of attack was about 8 miles.... The attack of the XVII Corps was to be carried out by the 34th Division on the right and the 37th Division on the left.... Zero hour was 4:25am on 28 April. During the night of 27th/28th the eighth Battalion.... Moved forward from Heron Trench and assembled in Cuba Trench; the Battalion was in position by 3am on 28th, two platoons in front and two in rear, as each attacking battalion had been ordered to advance on a two-platoon frontage. It was so dark when Zero hour arrived that it was impossible to see more than 20 yards ahead, British and Germans being indistinguishable. Compass bearings had been taken and given to officers and NCOs, but even so, when the attack went forward, there was loss of direction. A few minutes after Zero a very heavy hostile barrage fell on the line of the road and the smoke, combined with the darkness, caused considerable confusion, with the result that the Somersets swung off to the left and Cuthbert Trench (directly east of Cuba Trench) was only partially attacked, the full weight of the attack passing on to Whip Trench, which lay some 500 yards east of Cuthbert."

It was during this early morning attack on 28 April 1917 that Jack was killed when he was hit on the side of his head with a piece of shrapnel. He was just 22 years old. Two other Yeovil men, Richard Brown and Francis Sartin were killed in the same attack and died on the same day.

On 23 May 1917 the Western Gazette reported "Information has been received that Lance-Corpl. J Bindon, oldest son of Mr and Mrs E Bindon, 28 Beer Street, has been killed in action in France. He has been in the Army four years and served with his regiment in the earlier battles of the war. He was invalided home, and some time ago went out to France again, where he was killed. Prior to enlisting Lance-Corpl. Bindon was employed by Mr Llewellyn, fruiterer, &c, of High Street.

The Western Gazette reported in its edition of 15 June 1917 "Mr and Mrs E Bindon, of 28 Beer Street, Yeovil has been informed that their eldest son, Lance-Corporal WJ Bindon, of the Somerset Light Infantry, was killed in action in France on April 28th. The following letter has been received from his Company Sergeant-Major:- “I regret to tell you that “Jack” was killed on 28th of April, during our last attack. He is mourned by the whole of the boys here who knew him for he was a great favourite with everyone. He did not suffer in the least. He was hit on the side of his head with a piece of shrapnel, which caused instantaneous death. Kindly accept my deepest sympathy and also the sympathy of the whole of C Company.” The deceased soldier, who belonged to the Regular Army, having served four years, went to France in August 1914, subsequently taking part in the battles of Le Cateau, the Marne, the Aisne, and Ypres, being invalided home from the latter suffering from bronchitis. On returning to the Depot he was transferred to the – Battalion Somerset Light Infantry, and went to France some two years ago. During his stay in France he had several narrow escapes, having been wounded twice, and also having being twice buried. Lance-Corporal Bindon was 22 years of age, and was, prior to enlisting, employed by Mr Llewellyn, fruiterer &c, of High Street. Much sympathy is felt for his parents and family (there being another son serving) in their sad bereavement."

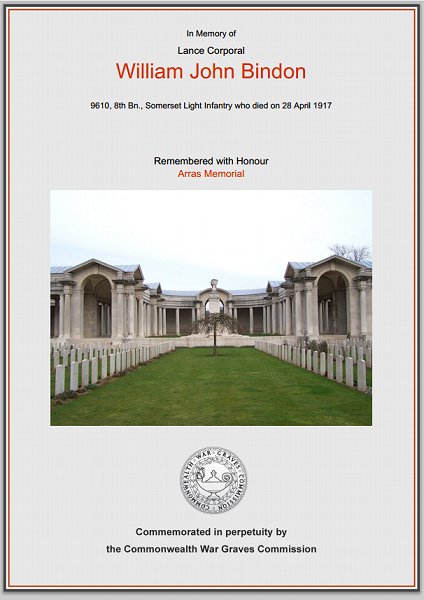

Jack Bindon is commemorated on Bay 4, Arras Memorial, Pas-de-Calais, France, and his name is recorded on the War Memorial in the Borough.

gallery

This colourised photograph of High Street, dating to about 1925, shows the building on the site of the George Inn - occupied by Denner and Stiby's ironmongery business until 1892 and then (at the time of this photograph) by Llewellyn's greengrocery and florist premises where Jack worked.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Jack Bindon.