education in yeovil

education in yeovil

An introduction

The First Schools

It is likely that a Choir School existed in the fourteenth century, associated with the parish church, as there is mention of a Choir School in Yeovil as early as 1380. In this school, not only music but certainly Latin and probably the "three R's" were taught. It would appear that this school existed until the Reformation.

However it is not until 1547 when that the Crown Commissioners, in the wake of the abolition of Chantries, were travelling the county and reported that the Chantry attached to St John's church was being used as a school - "chapel scituate in the church yarde.... which the inhabitauntes ther desire to have for a scholehouse". The churchwardens' accounts of 1573 show that a sum, of £12 13s 4d (in excess of £20,000 at today's value) was expended in converting the chapel to a school which included a bedchamber for the master. It is not known how long this school lasted.

In 1707 Martin Strong, the vicar of Yeovil, began a public subscription in order to endow a charity school "for 20 poor boys to be taught and closed after the manner used in and about London". The Yeovil Charity School, also known as the Free School and the Charity Grammar School, opened in 1709 providing a free elementary education for children up to the age of 12 or 13. This, it was claimed, was "the first in all this part of the world". Much of the children's education focused on the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer and once they had reached the age of 12 or 13 they were further helped to find apprenticeships. Mostly funded by endowments and subscriptions, the school provided a blue cloth uniform for the poorest pupils.

Dame Schools

A dame school was an early type of private elementary school, usually taught by women and often located in the home of the teacher. The quality of education received from such establishments was, to say the least, variable with some being little better than a daycare facility run by women who were all but illiterate. Frequently children were only taught the basics of reading and writing with little attention being paid to grammar, spelling or mathematics. Having said that, some dame schools did actually give a sound, basic education to their pupils.

Nevertheless, when the newly elected Yeovil School Board undertook a census in 1871 it discovered that eleven such dame schools in Yeovil were considered completely inadequate "by reason of the incompetence of the of the teachers and defective accommodation". In total, these dame schools accommodated 263 children, 195 of whom were under six years of age and the remaining 68 were aged between seven and thirteen.

As a consequence, the Board wrote to parents warning them of the inadequacies of such dame schools and also wrote to the dame schools informing them of their action. Indeed under the Education Act 1870, School Boards were enabled to enact bylaws and the first bylaw of the Yeovil School Board in August 1871 was the insistence on compulsory attendance at 'efficient' schools for all children between the ages of five and thirteen.

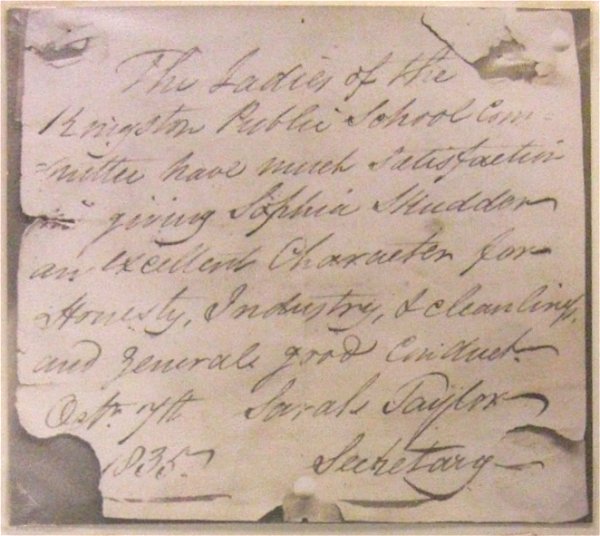

A school report from 1835 for a student attending a 'Dame School' in Kingston.

The National Schools

In 1839, a campaign started to open a day school for both boys and girls under the patronage of the Church of England and plans were made for a new school building in Huish.

Town Commissioner and retired glove manufacturer Robert Tucker acted as secretary for the campaign and donated a garden plot adjacent to the Calvinist burial ground as a site for the school. In April 1846 the National Day School opened for the education of children of poor parents "in the principles of the Church of England".

In 1856 Vickery wrote "In consequence of the very early age at which children are put to work at glove-making, this school is very thinly attended, and is at present but little removed from being an Infant School."

Clearly attendance improved because in 1867 the girls were moved to a Church Street building and a separate infants department was opened at Huish. It was around this time that a second National School opened, the South Street Girls and Infants School, accommodating 190 children in South Street.

The Education Act 1870, made provision for voluntary bodies to transfer their schools to the new School Boards should they so wish. Across the country this was seldom carried out, but in Yeovil the National Schools at Huish and South Street were handed over to the Board by the Anglican authorities.

The Board Schools

Even though much effort had been made by individuals, voluntary bodies, religious organisations and the like, there were still problems with England's education system as a whole and there arose a growing national demand for a better system of education.

The Elementary Education Act 1870 of Gladstone's government was a significant turning point in education by creating a unified, national system education and made possible the creation of schools under the control of locally elected school boards. These new board schools could charge fees and were also eligible for government grants, they could also be paid for out of local government rates. Board schools provided an education for the 5 to 10 age group and in some areas pioneered new educational ideas such as separate classrooms for each age group, a central hall for whole-school activities and specialist rooms for practical activities. School boards had the power to pay the fees of the poorest children and, if they deemed it necessary, were able to create a by-law making school attendance compulsory between the ages of 5 and 13.

It is difficult to assess the reaction to the Act within Yeovil, as with other towns. The educated, wealthy mercer classes often viewed the education of the masses with some caution and, indeed, many of the poor regarded the education of their children with some skepticism, preferring an additional income for the family over hours spent 'wasted' on education.

In January 1871 Yeovil's first School Board was elected; chaired by Wesleyan Minister Richard Thomas, the other six members were coal and timber merchant Jabez Bradford, glove manufacturers Elias Whitby (who was to serve on the Board for 29 years), Richard Ewens and William Raymond (who was to serve for 27 years), solicitor Henry Watts and retired draper and landowner John Curtis. George Custard was appointed as clerk to the board at an annual salary of £20 (about £10,000 at today's value), a position he was to hold for the next 33 years.

In order to determine how many children in Yeovil required places at school, the Board carried out a census in March 1871. This established that there were 1,187 children between the ages of five and thirteen and an additional 487 aged between three and five giving a total of 1,674. At this time Yeovil's schools could only accommodate just over 1,100 children. As a consequence the Board determined to build two new schools each able to accommodate a minimum of 150 children. These were to be built in Reckleford and London Road (today's Sherborne Road). In addition the Plymouth Brethren intended to erect a school for 78 children and the Wesleyan Methodists proposed building a school for 150.

The Education Act 1870 made provision for voluntary bodies to transfer their schools to the School Boards should they so wish. Across the country this was seldom carried out but in Yeovil the National Schools at Huish and South Street were handed over to the Board by the Anglican authorities. The Plymouth Brethren, on the other hand, chose to maintain control of their school which had been established at their place of worship in Vicarage Street.

While plans were put into place for the new schools the Board took on a 21-year lease on St John's Sunday School and, in order to reduce temporarily the number of school places required, school entry to children under five was discontinued. Later temporary schools were created in the Chantry and Victoria Hall, South Street.

Within a couple of years of being established, the Board reconsidered its building programme and decided to build just one school for 300 pupils. The Reckleford Infant and Elementary Schools opened in January 1876 with an initial intake of 33 pupils. Nevertheless despite such an initial small intake, by 1888 demand for places at the school required the board to enlarge it to accommodate 600 pupils.

In June 1873 the Yeovil School Board determined that each year the children would be given a total of six weeks holiday, comprising two weeks at Christmas, a week at Easter and three weeks in August. Two years later a week at Whitsun was added because most children "took it off in any case" to help on the farms and in gardens. In addition the children were also allowed a range of days or half days off for special events, including church tea meetings, Yeovil Show day, the annual Temperance Fete, and so forth. The headmaster at Reckleford School recorded in the school's logbook during one week in July that there had been two tea meetings, two band parades, Yeovil Fair and a demonstration at Ham Hill leading to the school being "barely attended".

In 1876 the Yeovil School Board fixed school fees at 2d a week per child (two old pence in 1876 is worth about £1 at today's value) at the infants school and 3d a child attending the other schools. Frequently fees were remitted in cases of hardship.

The Pen Mill Elementary School, St Michael's Avenue, was built to accommodate an ever-increasing population at the town's eastern end. With accommodation for some 270 children, the school opened in 1895.

The table below shows the 1886 time-table for 'Standard Two' at Reckleford School (albeit typical of most Board Schools at the time) and gives a very good impression of the activities of the school week with, as might be expected, a 66% concentration on the traditional 'Three Rs'. It was, in fact, at this time reading, writing and arithmetic that attracted government funding grants and therefore the bulk of the school week was devoted to these three subjects primarily for their greater earning capacity than other subjects. Later, other subjects were to be included in the grant funding with a resultant broadening in the range of subjects taught at the schools.

| 9:15 to 9:55 | 9:55 to 10:30 | 10:30 to 10:45 | 10:55 to 11:20 | 11:20 to 12:00 | 2:00 to 2:30 | 2:30 to 3:00 | 3:00 to 3:10 | 3:20 to 3:50 | 3:50 to 4:25 | |

| Mon | Reading | Writing | Mental Arithmetic | Spelling | Arithmetic | Tables or English | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Arithmetic | Writing |

| Tues | Arithmetic | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Drawing | Spelling | Tables or English | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Arithmetic | Writing |

| Weds | Writing | Drawing | Mental Arithmetic | Copy Books | Spelling | English or Geography | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Arithmetic | Writing |

| Thur | Arithmetic | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Spelling | Writing | English or Geography | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Arithmetic | Writing |

| Fri | Reading | Writing | Mental Arithmetic | Arithmetic | Drawing | English or Geography | Reading | Mental Arithmetic | Arithmetic | Drill |

The potentially contentious subject of religious instruction was, under the 1870 Education Act, left chiefly to the discretion of the individual School Boards. In 1872 the Yeovil School Board unanimously agreed to follow the practice of the London School Board that "In each of the schools under the Board, the Bible should be read and there shall be given by the responsible teachers of the schools such explanations and such instructions therefrom in the principles of religion and morality as are suited to the capacities of the children, provided always, that in such explanations and instruction that no attempt be made to attract children to any particular denomination." In consequence religious instruction was given to the children at the start of each day from 9:00am to 9:15am, in addition to the timetable above.

School Boards were abolished under the Education Act 1902 but during its thirty year lifespan the Yeovil School Board did much to improve elementary education in the town and by the turn-of-the-century almost 2,000 children were attending the four Yeovil Board Schools; Reckleford, Pen Mill, Huish and South Street.

Private Schools

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century Yeovil began to have a wealth of private schools. These ranged from individuals giving single-subject lessons one-on-one to paying students, often in their own homes or in the home of the student, to large boarding establishments that would develop, grow and prosper. Most private schools were boarding schools at which the students lived in accommodation usually on or near the school premises. Additionally some schools took in parlour boarders, for an increased fee. The parlour boarder was a special category of boarder, normally the child of deceased or wealthy parents, who was put in the care of the headmaster or headmistress of the school and, while attending classes with the rest of the students, was nevertheless treated as a cut above the other pupils.

In 1845 John Aldridge established a school in Clarence Street. By 1851 Aldridge had moved his school to a large house in Kingston, next to the Red Lion Inn. The school was to become known as Kingston School. It was to be enlarged and renamed Yeovil County School in 1905 following the Education Act 1902 and in 1925 was renamed yet again to The Yeovil School. The school moved to new buildings in Mudford Road in 1938 and in 1974 became part of Yeovil College.

During the 1880s Agnes Nosworthy founded a school for young ladies in Hendford, later transferring to The Park, known as Girton House School. Girton House School was later taken over by the Grove Avenue School and ultimately became Yeovil High School for Girls.

In 1891 Henry Cobb founded the Yeovil High School for Girls, colloquially known as Yeovil High School, together with Colonel Marsh and others. His daughter, Fanny Cobb, became its first headmistress initially with just a dozen pupils. She was to remain headmistress for 33 years. The school was eventually taken over by the County Council.