Summer Exhibition 2022

Secret Yeovil

Summer Exhibition 2022 - presented by Yeovil's Virtual Museum

![]()

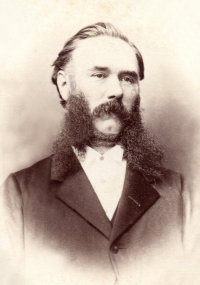

Middle Street, c1875. The three-storey house at left was the home and shop of murderers Robert Slade Colmer and his wife, Jane. |

|

![]()

Introduction

Of course,

very little

about Yeovil's

history actually remains

'secret', but

there is an

awful lot that

is less

well-known. This

exhibition is

therefore an

attempt to

uncover some of

the unfamiliar

facets of

Yeovil’s past,

concerning both

the town itself

and its people.

Much of the

information

included here

comes from my

book 'Secret

Yeovil',

although all

aspects of the

exhibition may

be found in much

greater detail

within Yeovil's

Virtual Museum,

the A-to-Z of

Yeovil's

History, and

hyperlinks are

given within the

text. Enjoy.

![]()

Secrets of the Streets

We begin with some name changes that have occurred to Yeovil's streets

through the

ages. Many name

changes are well

known; for

example Pyt Lane was the original name of Middle Street

probably because of a number of flax pits or tanning pits in the

vicinity.

Brickyard Lane,

with three

brickyards at

one time, became

St Michael's

Avenue and

Grope Lane,

with two

possible origins

(groping one's

way along the

dark, unlit lane

and a more

lascivious

explanation),

became Wine

Street. But

there are

several unusual

name changes

that are

long-forgotten

today.

At one time Yeovil's weekly markets were held in the streets with particular streets known for the livestock or produce being sold.

From my

collection. This

colourised photograph

features in my

book 'Secret Yeovil'.

A postcard of about 1905 (this one was posted in 1911) showing the Town Hall beyond the weekly market in the Borough.

|

The nineteenth century saw a subtle gentrification of parts of Yeovil resulting in some name changes, so Hog Market (by the Three Choughs, seen at left) reverted to Hendford, Cattle Market was renamed Princes Street, Sheep Lane became North Lane (both names being preferable to its earlier sobriquet, Shitt Lane) and Cornmarket once again became Silver Street. It was noted in 1846 that "Some 4,000 sheep and 600 beasts thronged Cattle Market and Sheep Lane".

|

|

Silver Street had been known by several

names; in the 16th century

it was referred to as Stairs Hill, alluding to the steps in the

churchyard

wall.

A road called Silver Street often implies nearby water and, in Yeovil’s

case,

the

Rackel

stream

(now

below ground) created a shallow ford across the road, by the

Pall

Tavern.

In the 12th century,

the road

on the

other

side of

the ford

was

known as

Ford

Street later called Rackleford - the ford across the Rackle. In the 19th century it was called Rotten Row and was a horse market but today it is

known as

Market

Street.

|

In 1825, "the new road belonging to Peter Daniell" was a road which, combined with Park Street running from the east, replaced the circuitous and very steep route of Addlewell Lane and Chant's Path. The new road was originally called New France although after a couple of years the 'New' epithet had worn off and the road became known as France Street. By 1835 it had acquired the name by which it is known today - Brunswick Street.

|

Larkhill Lane, seen at left from Preston Road, became today's Larkhill Road but was earlier known, certainly as late as 1841, as Down Lane and beyond the Thorne Lane crossroads it was known as Ashley Lane.

There

was a

John

Sperwe,

or

Sparrow,

whose

will

leaving

lands in

Yeovil,

is dated

1417.

What we

know

today as

Sparrow

Road was

called

Sparrow

Lane

until

the

1840s

but from

the

1850s to

the

1880s it

was

called

Coalpaxy,

or Colpexin,

Lane. |

At one time

there was a

continuous route

from Yeovil to

Ilchester by

ancient

footpaths and

tracks. It

started at

Kingston with

Red Lion Lane,

continued along

Roping Path to

Mudford Road. It

then crossed the

road and entered

a large field

called

Green

Cross, lying

roughly between

the modern

southern

entrance to

Yeovil College

and

Goldcroft.

Green Cross

probably spanned

both sides of

Mudford Road,

albeit chiefly

to the west. As

it continued,

the footpath was

known as

Hillon

Path and is

referred to in

the

Terrier of

1589.

|

Penn Way was a lane across the lower western slopes of present day Wyndham Hill, seen at left. Penn Way commenced close to the Newton Road site of the later Penstyle Turnpike gatehouse, (today the site of Ivel Court) apparently as a lane, little better than a track, for a short distance before continuing as a footpath, roughly following along the route of today's Railway Walk, to Yeovil Bridge. Penn Way even had a pub - The Sun. |

|

George

Court

was

little

more

than an

alleyway

linking

High

Street

with

South

Street

and

flanked

with

ruinous

buildings

and had

something

of an

ill

reputation.

In

keeping

with

other

'courts'

of

all-but

slum

housing

in

Yeovil,

George

Court

was

usually

home to

several

poor

families

at any

one

time.

George

Court

also had

stables,

so with

them,

the meat

market

and the

cheese

market

along

the

western

side,

the air

in the

narrow

Court

must

have

been

quite

'special'.

|

|

Colloquially

known as

the Swastika

Terraces,

two

un-named

terraces

of

houses

in Grass

Royal

feature

decorative

swastika

patterns

formed

in

cream-coloured

brickwork.

This

contrasts

with the

local

red

Yeovil

bricks

that

were

almost

certainly

made

just

around

the

corner

at the

brickworks

in

Brickyard

Lane,

today's

St

Michael's

Avenue.

|

![]()

Secrets of St John's church

The Iron Cross

In 1415, the year of Henry V’s victory over the French at Agincourt, the

king personally

laid the

foundation stone

of the Convent

of Syon at

Isleworth,

Middlesex. In

1420 the Abbess

and 35 nuns took

possession of

the convent,

properly known

as ‘The

Monastery of St

Saviour and St

Bridget of Syon

of the Order of

St Augustine’.

It was built as

part of 'The

King's Great

Work'.

|

In order to part-support the convent, Henry granted them the Yeovil rectory of St John the Baptist and Lordship of the Borough of Yeovil together with ‘two acres of land in Huish and a portion in Martock’. For the next 114 years, until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1534 by Henry VIII, Yeovil came under the jurisdiction of the Abbess and was administered locally by a resident bailiff in conjunction with the Portreeve and Burgesses. |

There is a little-known small iron cross fixed to the eastern parapet of St John's church tower indicating that the church was exempt from taxation while the borough was held by the Convent of Syon between 1420 and 1534.

|

The

Weathercock When the present weathercock was erected in 1745 The Churchwardens' Accounts recorded that the cost was £3 5s 6d (£1 4s 0d for supply and a further £2 1s 6d for gilding and erection - £3 5s 6d at today's price, but around £550 at today's value). |

The Lectern

A lectern (from the Latin lectus,

"to

read")

is a

reading

desk

with a

slanted

top,

placed

on a

stand,

on which

books or

documents

are

placed

as

support

for

reading

aloud,

as in a

scripture

reading,

lecture,

or

sermon.

St

John's

double-desk

lectern, is referred to in old records, such as the

Churchwardens'

Accounts,

as the 'Dext'.

It is

inscribed

in Latin

and is

complete

with a

picture

(later

defaced)

of the

donor

monk,

Brother

Martin

Forester.

The

Latin

inscription,

in Blackletter,

reads -

"Precibus

nunc

precor

cernuis

hinc eya

rogate.

Frater

Martinus

Forester

vita

vigiletque

beate."

This

roughly

translates

as "I

pray you

now

offer

humble

prayers

so that

Brother

Martin

Forester

may

awaken

in the

blessed

afterlife".

The lectern was acquired by the Churchwardens of St John's, John Hacker

and John

Parker,

in 1541

at a

cost of

£3

(about

£16,000

at

today's

value).

St John's church houses an exceptional and rare English lectern which

dates to about

1450 - just a

few decades

after the church

itself was

built. It is one

of only four of

its type in the

entire country

and is the sole

example still in

a parish church

(the others are

at Eton College,

Berkshire,

Merton College,

Oxford and

King's College,

Cambridge).

The Bosses and

'African' Masks

People rarely look upwards inside buildings, which is a pity as much is

missed -

especially in St

John's church

where there is a

wealth of

medieval carved

roof bosses in

the nave,

chancel and

aisles. You will

need a pair of

binoculars to

see them

properly. The

bosses are

thought to date

to 1404-5 when

the construction

of the church

was nearing

completion.

|

There are many bosses featuring flowers, foliage or abstract designs but a woman’s head features, as do the head of a man and the head of Christ. One boss has four faces and another is of a horned man – perhaps Satan looking down on the congregation? At left is the face of Robert de Sambourne, builder of today's St John's church. The painting seen on the bosses today is, of course, modern. Whether or not the bosses were painted originally is not known but unlikely, certainly not in the bright colours seen today.

Additionally, there are roof bosses in the form of grotesque 'African'

masks,

numbering

about 30

in all

and

located

primarily

in the

north

and

south

aisles.

The

dating

above is

thought

to be

also

applicable

to the

'African'

bosses.

Probably

unique,

the

origins

of these

strange

bosses

are

unknown. |

The Black Halos

The parish church of St John the Baptist has long been known as the

'Lantern of the

West' because of

the superb,

large windows

which admit such

a flood of

light. The

windows are an

early example of

fully developed

Perpendicular

Gothic with the

tracery of the

Reticulated

Transitional

Perpendicular

style, dating to

between 1380 and

about 1400.

|

The south window of the south transept was inserted in 1862 as a memorial to John Greenham and his wife Elizabeth from their children. It cost £210 (around £130,000 at today's value) and depicts the Last Supper. This window portrays Judas Iscariot with a black halo. The east window was inserted in 1863 showing scenes from the Passion and here too Judas is represented with a black halo - a feature thought to be unique to St John's church.

|

|

The 'Secret'

Church Mice |

![]()

Social Matters

The hundred was headed by a Hundred-Man or Hundred Elder and in the

immediate

post-Conquest

period the

duties of the

Hundred Elder

included

organising,

supplying and

leading the

military forces

of the hundred.

Since in return

for being

granted the use

of a hundred

hides of land,

technically the

'property' of

the king in the

Feudal system,

the men of the

hundred were

bound to supply

one hundred men

for military

service when

required by the

King.

The Hundred

Stone

The 'hundred' was a tenth century Saxon division of the shire for

judicial and

military

purposes. The

geographic area

of the hundred

was the land

required to

sustain

approximately

one hundred

households.The hundred usually took the name of the main town in the area but in

Yeovil it was

called the

Hundred of Stone

in reference to

the local

landmark, the

Hundred Stone,

at the junction

of today's Stone

Lane and Mudford

Road - the

highest point in

Yeovil and its

hinterland. This

was the

traditional

hundred meeting

place, where the

Hundred Court

was held. The

Hundred of Stone

not only

included Yeovil,

but Odcombe,

Brympton,

Preston

Plucknett,

Limington,

Ashington and

Mudford and

covered 10,720

acres (4,340

hectares). The

Hundred of Stone

was one of forty

historical

hundreds in

Somerset.

The principal responsibility of the hundred gradually focused on the administration of law and justice within the area. By the twelfth century the Hundred Court would meet in the open around the Hundred Stone each month. The hundred was divided into ten tithings, each containing ten householders and their families. Each tithing was responsible for all that went on in its own small area and those living within the tithing were collectively responsible for each other’s behaviour. Twice a year representatives of each tithing attended the Hundred Court to give a report of the conduct of their members and to admit as new members all males who had reached the age of twelve years.

The administrative importance of hundreds decreased after 1834 although they were still used as a unit for census purposes until 1850. The last recorded meeting of Yeovil's Hundred Court at the Hundred Stone was in 1843.

The Yeovil Riot

of 1349

In Yeovil there had been a longstanding dispute concerning taxes and

other

constraints

regarding market

rights and tolls

and Sunday

trading placed

on the

townspeople of

Yeovil by the

Church. Across

the country

survivors of the

1348 plague, perhaps encouraged by their survival, assumed a more militant

stance than

previously and

in Yeovil

simmering

grievances came

to a head in

November 1349.

Just a couple of

months after the

plague had

ended, their

resentment

against the

Church turned

into a

full-scale riot.

On Sunday 25 November 1349 during a Visitation by Bishop Ralph of

Shrewsbury, the

Bishop of Bath

and Wells, the

anger and

dissatisfaction

of the people of

Yeovil came to a

head and

violence

erupted.

The mob

attacked the

Bishop and his

entourage who

were forced to

retreat within

the church (the

Saxon church,

not today's

building), where

they remained

all night.

The following morning some of the rioters broke into the church. As one of the priests tried to talk with the mob, their ringleader, Roger de Warmwelle, struck the priest and the mob erupted. Of course, there were dire consequences. The church itself was interdicted by the Pope and the townspeople who had taken part in the riot were excommunicated. Roger de Warmwelle and a number of the other rioters were fined and made to do public penance and suffer humiliation at Yeovil, Bath, Wells, Bristol, Somerton and Glastonbury.

Beating the

Bounds and the

Hound Stone

Beating the bounds was an ancient custom dating back to Anglo-Saxon times

(it was

mentioned in the

laws of Alfred

the Great) in

which a group of

old and young

members of the

community would

walk the

boundaries of

the parish. They

were usually led

by the parish

priest and

church

officials, to

share the

knowledge of

where the

extents of the

parish lay, and

to pray for

protection and

blessings for

the lands of the

parish.

Since there were few, if any, maps in former times it was usual to make a

formal

perambulation of

the parish

boundaries

during Rogation

Week. Some

places on the

outer limits of

the parish might

be marked with

boundary stones,

such as the

Hound Stone in

Thorne Lane,

seen below.

Perambulation means "walking around" and in traditional English law, it is used specifically to mean "determining the bounds of a legal area by walking around it", meaning physically walking around the parish boundaries. In such a way the parish boundaries were verified annually. Also known as 'Beating the Bounds', it was an important custom since knowledge of the boundaries of each parish needed to be handed down to ensure, for instance, that liability to contribute to the repair of the church, or the right to be buried within the churchyard was not disputed.

The

Hound Stone,

an 18th century

boundary marker,

is located on

the northern

side of Thorne

Lane at Thorne

Cross (the

staggered

crossroads of

Western Avenue

and the Thorne

Coffin road).

According to local tradition, the Hound Stone

(now gradually

being enveloped

by a growing

tree) was the former meeting place of the local hunt, hence

the name Hound

Stone, which was

also then

applied to the

district to the

south. This, of

course, is

completely

erroneous since

'Hundestone' was

actually

recorded as the

name of the area

in the Norman

Domesday Book of

1086.

![]()

Yeovil at Work

Evidence

of Early Farming

During the Middle Ages farming was one of the most important livelihoods

in the market

town of Yeovil

and its

immediate

neighbourhood.

Traces of

medieval farming

practices still

exist today in

the form of

lynchets

(from the Old

English

hlinc

meaning 'ridges,

terraces of

sloping ground')

on the lower

slopes of

Summerhouse Hill

- showing as a

series or flight

of stepped

terraces,

visible on the

now grassy

hill-side.

A lynchet, also

known as a strip

lynchet, is a

bank of earth

that builds up

on the downslope

of a field

ploughed over a

long period of

time.

They are

slowly

formed

by

disturbed

soil

slipping

down the

hillside

to

create a

lynchet.

Lynchets

therefore

represent

the

legacy

of

ploughing,

although

not

necessarily

consciously

created

as a

feature,

though

some

initial

construction

may have

been

required

on the

steepest

ground.

The lynchets are the result of the repeated action of the plough's mould-board turning the loosened soil outwards and downwards; over time forming a level strip or tread for cultivation with a scarp slope (a 'riser') down to the next strip below. Reflecting the practical nature of their creation, they follow the contour lines of the natural slope. The northern flanks of Summerhouse Hill still retain these reminders of Yeovil's medieval farming past.

Minting

your own Money

Following the death of Charles I in 1649 no copper coinage was minted

during the

Commonwealth.

The resulting

paucity of small

coinage was met

by

independently-produced

and completely

unauthorised

coins - actually

trade tokens

- of brass,

latten (a copper

alloy similar to

brass) or

pewter. Most

Yeovil trade

tokens were

issued by

tradesmen in

order to

overcome the

lack of small

change in

general

circulation and

enable trading

activities to

proceed. The

token was, in

effect, a pledge

redeemable in

goods although

not usually for

currency.

These tokens never received official sanction from government but were accepted and circulated quite widely. Even the Portreeve, on behalf of the Borough of Yeovil, minted and issued halfpennies, seen above, during 1668 and into 1669. From 1672, in the reign of Charles II, official farthings and halfpennies were minted again with the consequent demise of trade tokens. The value of a farthing in the 1650s was roughly equivalent to £2 at today's value.

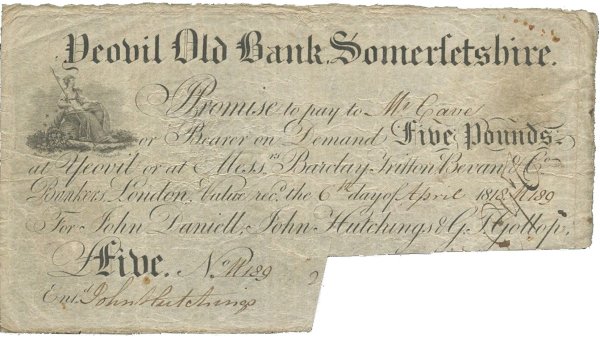

During the end of the eighteenth century a number of private banks were established in Yeovil. Private banks were allowed to issue their own banknotes. Far from being ordinary currency as we are used to today, the £1, £5 and £10 notes issued by these banks were not for use in everyday shopping transactions. For example the £5 banknote of Yeovil Old Bank issued in 1818 illustrated here would have a value of about £335 at today's value.

Dobell

Clockmakers

Robert Dobell

was born in

Wiltshire in

1808. He married

Elizabeth Tucker

at St John's

church in 1830 -

the same year

Pigot's

Directory listed

him as a "Watch

& Clock Maker of

Middle Street".

In the autumn of

1837 Elizabeth

died and in the

spring of the

following year

Robert married

Mary Ann Hardy

at St John's

church.

|

Robert

was

listed

as a

'Watch &

Clock

Maker of

Middle

Street'

in the

Somerset

Gazette

Directory

of 1840.

In the

1841

census

he was

listed

as

living

with his

new wife

Mary,

three

children

and a

servant

in

Hendford

on the

corner

of High

Street.

35-year

old

Robert

gave his

occupation

as a

Jeweller.

|

In the 1861 census, 53-year old Robert and 19-year old Frederick, together

with a domestic

servant, were

listed at

Hendford and

both father and

son gave their

occupations as

Jewellers.

Robert Dobell

died in the

spring of 1868

aged 61. His

business was

carried on by

Frederick.

Brickmaking

Yeovil clay was suitable for brickmaking and several brickworks were to be found in the town producing the soft, bright red bricks found everywhere in the older parts of Yeovil. The main Yeovil brickfields, seen below, were located north of Reckleford in the general area of Eastland Road, at this time known as Kiddle's Lane. Early maps show a clay pit from which the raw material was obtained as well as a brick kiln to the northwest of Dampier Street and to the east of Kiddle's Lane.

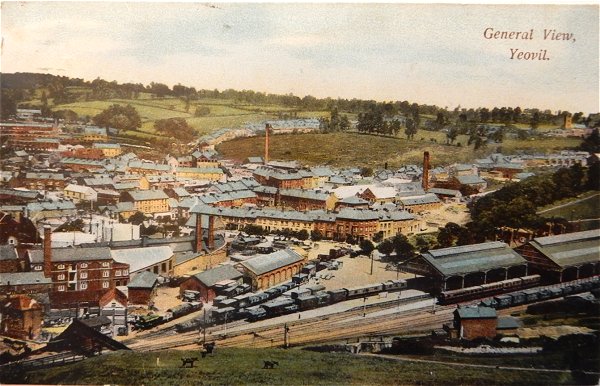

From my

collection

This postcard dates to about 1905 and shows, at centre, the chimney of the Yeovil Brickfields Co Ltd on the southeast corner of Eastland Road with its associated buildings clustered around its base. Running across the centre of the photograph is Station Road with the Alexandra Hotel at right. In the top half of the photo, Eastland Road runs behind the chimney with fields either side!

Extensive brickworks were also to be found at St Michael's Avenue which, indeed, was originally known as Brickyard Lane. The section from Milford Lane to Mudford Road was still called Brickyard Lane on the 1928 Ordnance Survey. There some fourteen other, smaller brickworks in the town such as at New Town, Preston Road and Ilchester Road.

Most

of the Yeovil

brick-making

sites were small

in scale and

didn't last for

long, which

suggests

short-term

investment by

builders and

others to meet

new local

housing needs.

In fact the

majority of

Yeovil's brick

makers were

already in the

building trade.

The Yeovil Motor Car

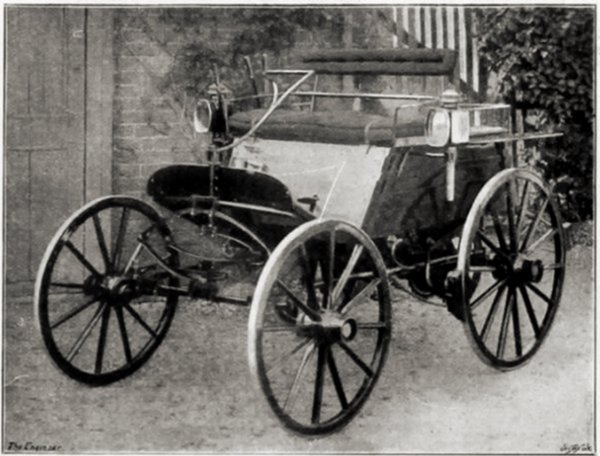

James Petter’s twin sons, Ernest and Percy, had always been interested in transport and even at the age of twelve Percy, under the guidance of his eldest brother, had "made some hand-propelled velocipedes.... and later used to hire a wood wheeled 'penny farthing' boneshaker. By 1892 Percy and Ernest had designed and produced a self-propelled oil engine and in 1895, together with their inventive engineer, designer and foreman Ben Jacobs (who remained in service with the Petters until he was in his late seventies), they developed a new engine of one horse-power designed specifically to propel a 'horseless carriage'. They produced the first motor car with an internal combustion engine to be made in Britain, using a converted four wheel horse-drawn Hill and Boll phaeton and a 3hp Petter horizontal oil engine. The vehicle was constructed at the Park Road carriage works of Hill and Boll. It had a top speed of twelve miles per hour.

The Yeovil Car - the first motor car with an internal combustion engine to be made in Britain. This photograph appeared in the 3 April 1896 edition of 'The Engineer' magazine, captioned "Petter and Hill & Boll's Oil-Motor Carriage" with an accompanying article and plans.

Believing they had a great opportunity the brothers, with their father,

formed the

Yeovil Motor Car

Co Ltd in 1895

with a thousand

pounds capital

and a factory

was built on the

site of James'

garden in

Reckleford,

later to be

expanded as the

Nautilus Works.

The company was

to make small

two-person motor

carriages,

initially at

their foundry in

Huish / Clarence

Street and then

at Reckleford in

conjunction with

carriage makers

Hill & Boll of

Park Road. In

all,

some twelve

different

'horseless

carriages' were

developed. This

same year the

company was one

of four that

offered

automobiles for

trials at

Chelsea and

their twelfth

model, the

'Yeovil Car',

was exhibited at

the 1897 Motor

Car Exhibition

held at the

Crystal Palace.

Yeovil's Commemorative Medallions

It has long been a tradition for Yeovil schoolchildren to receive a commemorative medallion at the times of the monarch's jubilee or other celebration.

The above medals are, from left to right,

The Diamond Jubilee medallion celebrating Queen Victoria's 60-year reign, inscribed "Presented by the Directors of the Western Gazette and Pullman's News Newspapers Co Ltd. 1897".

A scarce commemorative medallion given to Sunday school children of Yeovil by the then Mayor of Yeovil, Sidney Watts, to commemorate the 1893 marriage of HRH Prince George (1865-1936), later King George V (reigned 1910-1936), to HSH Princess Mary of Teck (1867-1953).

Another scarce commemorative medallion given by Henry Stiby, later Mayor of Yeovil, to school children to commemorate the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII (reigned 1901-1910) and Queen Alexandra (1844-1925).

This commemorative medallion was given by Henry Stiby to younger schoolchildren in 1911 to commemorate the coronation of King George V (reigned 1910-1936).

![]()

Some Lesser-Known Yeovilians

John Perry

Technical

Blacksmith and

Temperance

Hotelier

John Perry was born in 1810 in Somerton and moved to Yeovil around 1839 with his wife Jemima and their first two of five children. They initially lived in Park Street and John worked as a journeyman whitesmith (tinsmith). By 1851 John had moved his family to Hannam's Lane (today's Tabernacle Lane) where he took over Henry Bragg's smithy.

John

regarded

himself

as a

'Technical

Blacksmith'

and

created

intricate

clockwork

mechanisms

as later

described

in a

journal

of 1899

-

"Amongst

local

inventions

the

clockwork

'modles'

of the

late

John

Perry of

Yeovil,

take

high

rank.

They all

worked

by a

penny-in-the-slot

arrangement.

There

were

about a

dozen of

them,

such as

a church

showing

ringers

at work

in the

belfry,

a man at

a pump

pumping

lemonade

into a

glass, a

smith's

workshop,

etc.

They

were

exhibited

at a

working

man's

exhibition

in

London.

First

shown in

Tabernacle

Lane,

Yeovil,

and

afterwards

at fairs

all over

the

country."

Certainly

by 1856

John

Perry

was

running

Perry's

Family &

Commercial

Temperance

Hotel

in

South

Street

and was

hosting

temporary

photographic

portrait

rooms to

visiting

professional

photographers.

The

hotel

was

across

the road

from

Hannam's

Lane and

was

situated

between

the

Globe

and

Crown

and the

Baptist

Chapel.

In August 1865

Hanham & Gillett

sold their

ironmongery

establishment in

the Borough to

John Petter and

at this time

John Perry,

having also been

the manager of

Hanham &

Gillett's

workshops for

some 23 years,

set up his own

engineering

business in

South Street in

partnership with

his son.

Doctor William

Fancourt Tomkins

Surgeon of

Magnolia House

and Borough

House

William Fancourt

Tomkins was

born in Yeovil

in 1825, the

eldest of the

seven children

of Yeovil

surgeon

William Tomkins

and Hannah née

Holland. He was

brought up in

the family home

of

Magnolia House

in

Princes Street.

|

William qualified as a Doctor of Medicine and was noted as such in the 17 September 1846 edition of the London Medical Gazette. He was admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons in January 1847. In the 1851 census William Snr gave his occupation as "M.D. London College Consulting Physician" and his eldest son, 26-year old William Fancourt, gave his occupation as a "Practicing Surgeon". On 30 October 1855 at Piddletrenthide, Dorset, William married 34-year old widow Sarah Palmer, formerly Sarah Flower. William and Sarah set up home at Borough House in High Street, which also served as William's medical practice until his retirement around 1890. |

Henry Monk

Headmaster of

Yeovil Charity

School and

Yeovil Grammar

School

Henry Monk was born in 1833 in Harrow Weald, Middlesex, the son of James and Mary Monk. Henry was a student at St Andrews College, Harrow. In May 1859 he was elected to the post of Master of the Yeovil Charity School which marked his move to Yeovil. On 9 January 1860, at the age of 27, Henry married Elizabeth Henrietta Hawkins at Harrow All Saints Church, Harrow Weald. They were to have nine children. In the 1861 census Henry and Elizabeth were living on Sherborne Road. Henry gave his occupation as 'Grammar Schoolmaster' while Elizabeth listed her occupation as 'Superannuated from the War Department'.

A photograph of Monk's school dated 1909. Henry Monk is at right and his daughter Edith at left.

During the 1860s Henry and Elizabeth moved to Hendford Hill where Henry opened his own school. In the 1871 census Henry and Elizabeth and their children were listed at Hendford Hill together with eighteen boarding pupils, a cook and a nursemaid. Henry simply gave his occupation as Schoolmaster. In the 1870s Henry moved his family yet again to 8 Hendford, today known as Flowers House. This was to become famous towards the end of the nineteenth century as Mr Monk's Grammar School.

Henry moved from Hendford to the Chantry in Church Path in 1897 (presumably due to the sharp drop in the number of pupils attending) and the Grammar School in Hendford was put up for sale. By 1901 Henry had moved his family to Ashgrove, Mudford Road. He was listed in the census as a 68-year-old schoolmaster with 67-year-old Elizabeth and three of their children. Henry was still teaching in 1909 at the age of 76, but by 1911 he had retired and was living in Ryme Intrinsica, Dorset, with Elizabeth and their two daughters Edith and Laura.

Frederick Cox

Builder of

Frederick Place

Frederick Place connected Middle Street with Vicarage Street for pedestrian traffic and had houses on both sides until the 1970s. It is now a link from Middle Street to the Quedam shopping centre. Frederick Place was named after Frederick Cox, a local builder, who had a builder's yard there in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Frederick Cox was a Freemason, initiated into the Lodge of Brotherly Love in Yeovil on 14 August 1861. He served as Worshipful Master of the Lodge in 1868 and the photograph below shows him in his Masonic regalia.

|

Frederick Cox was born in 1825, the son of builder and Town Councillor John Cox and his wife Mary. By 1881 Frederick was married, had seven children, two servants and was still living in Middle Street. He listed his occupation as 'Builder employing 25 hands'. Three local projects built by Frederick Cox were the Fiveways Hospital (1871), the Congregational Church in Princes Street (1877) and the Corporation Baths in Huish (1885). The carved stone head on the arch keystone above the Middle Street entrance to Frederick Place is reputed to be a likeness of Frederick Cox although it clearly isn't and the stone head isn't as old as you might think, dating from when the adjoining Albany Hotel was rebuilt in 1873. |

Frances Connelly

Yeovil's first Lady Voter

Women were not

allowed to vote

in Great Britain

until the 1832

Reform Act and

the 1835

Municipal

Corporations

Act. However it

would not be

until 1872, with

the formation of

the National

Society for

Women's Suffrage

and later the

more influential

National Union

of Women's

Suffrage

Societies that

the struggle for

women's voting

rights became a

national

movement. By

1906 the

movement was

beginning to

shift opinion in

favour of

women's suffrage

and it was then

that the

militant

campaign began

with the

formation of the

Women's Social

and Political

Union. In 1918,

a coalition

government

passed the

Representation

of the People

Act 1918,

enfranchising

women over the

age of 30 who

met minimum

property

qualifications.

Ten years later,

in 1928, the

Conservative

government

passed the

Representation

of the People

(Equal

Franchise) Act

giving the vote

to all women

over the age of

21.

|

However, the first female to vote in Yeovil was Mrs Frances Connelly of Reckleford who claimed, and cast her vote, in November 1911. The following report is from the Taunton Courier & Western Advertiser's edition of 29 November 1911 "The election will be remembered for the first time in the history of the constituency a woman claimed and was allowed to exercise the Parliamentary franchise. At the very moment a Suffragist's car was touring Yeovil displaying to an amused crowd the legend "Mothers want votes", a lady was putting her cross against the name of Mr Aubrey Herbert - at least she is supposed to be on the Unionist side - at the Town Hall. Mrs Frances Connelly, of Reckleford, Yeovil, discovered that her name was on the register and claimed to vote. |

The presiding officer (Mr WW Henley) demurred. The lady consulted the Conservative agent, Mr Harold Fletcher, who, having in turn discussed the situation with Mr WT Snell, barrister of the Western Circuit, who happened to be assisting in the Committee room. He interviewed the presiding officer and represented to him that the lady's name being on the register he had no alternative but to allow her to vote, the only conditions being that she was the person described on the register and had not previously voted in the election. The point was carried, and Mrs Connelly voted. What is more her vote was recorded in the ordinary way - not upon a 'tendered' paper - and was counted with the others."

Frances Connelly

died in Yeovil

in 1917, aged

48.

Fred 'Johnny' Hayward

Holder of a record that will remain unbeaten

Fred Hayward,

known as Johnny,

was born in

Yeovil in the

spring of 1887.

He was the

youngest of the

seven children

of glove cutter

William H

Hayward and his

wife Mary Ann

née Tutchings.

When he was

little the

family lived in

Wellington

Street, moving

to

Huish by the

time 14-year old

Fred/Johnny was

working as a

solicitor's

clerk. His

career in law

was short lived

and most of his

working life was

spent as a glove

cutter like his

father. In

August 1912 he

married Mabel

Alice Harbour.

They set up home

in

Everton Road

and were to have

seven daughters

and two sons.

|

Johnny's passion was football and from April 1907 he played for his local team, Yeovil Town Football Club. Johnny played for the club until 1927, usually positioned as centre forward and for many years captaining the team. His football career was interrupted by war service when he enlisted in the Machine Gun Corps during May 1916. Nevertheless, despite this wartime interruption in his football career, Johnny Hayward holds the record for being the highest goal scorer for a single club in the history of English football. During his career he achieved an extraordinary number of goals - at least 548 (some data on matches in those days was incomplete) and claims a record that will surely never be beaten. |

At his peak, he

netted 52 goals

in just 33 games

during the

1919-20 season

and 50 more in

the 1921-22

season.

Fred 'Johnny'

Hayward retired

from football in

1927 and died in

1958 aged 71.

![]()

Dark Deeds

A Few 'Snippets'

We begin with

some crimes that

would, perhaps,

today be

considered less

than heinous yet

occasionally

were accorded

the ultimate

punishment. We

start with some

snippets from

the past, in

date order.

"To Ivelchester

Gaol: William

Scott and

Margery Chapeley,

his mother, for

burglary; Scott

is twenty-three

years of age,

about five feet

high, was born

at Yeovil."

Police

Gazette, 29 July

1774.

"Wednesday

executed at

Ilchester, Alex.

Pearce, aged 19,

for setting fire

to his master's

[Thomas Garland

of the

Greyhound Inn,

South Street]

house and

stables at

Yeovil....

Alexander Pearce

was born at

Sherborne, and

apprenticed to a

tailor, but

losing a finger

by accident, was

obliged to

decline that

business, and

turned labourer.

Many strong

circumstances

appeared on his

trial, which

plainly proved

his guilt,

though he

declared his

innocence to the

last of ever

having any

knowledge of the

fact for which

he suffered. He

appeared very

insensible of

his approaching

fate, and

declared that he

had never robbed

or intentionally

injured any

one."

Bath

Chronicle &

Weekly Gazette,

2 September 1790.

"Gibraltar, March 6 1768. A private Soldier of the 19th

Regiment under

my Command here,

has confessed

himself a

Murderer,

enclosed I have

taken the

Liberty to

transmit to you

a Copy of his

Confession, viz.

"I Nathaniel

Jones, Soldier

in the 19th

Regiment, in

Chapel Norton's

Company, do

confess, that

about the Month

of April, 1765,

I murdered a

Woman dressed in

a Stamped Cotton

Jacket, and a

Check Apron (the

Colour of the

Petticoat I

forgot) near

Yeovil in

Somersetshire,

in the cross

Country Road

leading from

Beaminster to

Yeovil; and then

having taken

what Money I

could find upon

her, threw her

into a Marl Pit

near thereto."

Derby Mercury,

22 April 1768.

"On Thursday evening a quarrel took place at the

Penn Mill Inn

[not today’s Pen

Mill Hotel, but

a cider house on

the Sherborne

side of the

railway line],

near Yeovil,

between a

journeyman

glover, named

Allen, and an

itinerant dealer

in corks, named

Smith, in

consequence of

which the former

challenged the

latter to a

fight. Smith,

who was in some

degree

intoxicated, was

at first

unwilling to

comply; but,

provoked by his

antagonist, and

urged on by his

wife, he at

length entered

into the contest

and in the

second round

received a blow

to the neck,

which, in the

state of

excitement

arising from

liquor and the

anger he was in

at the moment,

caused instant

death. A

coroner’s

inquest was held

on the body on

Friday evening,

by Mr Uphill,

when a verdict

of

'Manslaughter'

was returned

against Allen,

who has

absconded."

Western Flying

Post, 9 October

1828.

"A banditti of turnip stealers, forty in number, attacked

and cruelly beat

the four sons of

Mr Symes, a

farmer, of

Yeovil,

Somerset, who,

with five

others, were

stationed to

protect a turnip

field from their

depredations....

Although two of

the farmer's

party were so

much beaten that

their lives are

in danger, they

succeeded in

repelling the

plunderers, and

securing three

of them, who are

committed to

Ilchester gaol

for trial."

Stamford

Mercury, 12

December 1916

From my

collection

A contemporary sketch of Ilchester Gaol, the temporary residence of many a Yeovilian.

|

Yeovil's Stocks |

For

centuries

Yeovil, like

most towns,

possessed a set

of stocks. These

were situated

between the

pillars of the

Market House

-

essentially a

roof supported

by columns that

covered the

market traders'

stalls -

that stood in

the middle of

the

Borough.

Yeovil’s stocks

were last

occupied on

Thursday 24

September 1846

by a man named

Stoodley. He was

found guilty of

being drunk on a

Sunday afternoon

and was confined

in the stocks

for three hours.

Death of a Mendicant

James Beare

became one of

Yeovil's early

law enforcement

officials, known

in the 1830s as

a Watchman, and

was based at the

Tolle Hall

in

the Borough.

The

town's

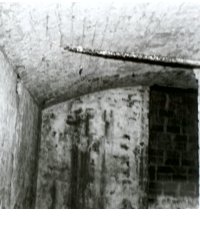

Watch-House or

lock-up (seen

at left) was in

cellars of the

building where they remain today,

roughly beneath

the

War

Memorial.

On 8 January 1838 a drunken mendicant, or beggar,

42-year-old

Isaac Justins, was thrown in the cells

but left there

without food,

water or heat

for two days,

resulting in his

death.

Consequently

James Beare, and

co-Watchman

George Hill,

were charged and

tried for

manslaughter.

The

town's

Watch-House or

lock-up (seen

at left) was in

cellars of the

building where they remain today,

roughly beneath

the

War

Memorial.

On 8 January 1838 a drunken mendicant, or beggar,

42-year-old

Isaac Justins, was thrown in the cells

but left there

without food,

water or heat

for two days,

resulting in his

death.

Consequently

James Beare, and

co-Watchman

George Hill,

were charged and

tried for

manslaughter.

It

must be presumed

that the case

against James

Beare was

ultimately

dismissed

although he

almost certainly

lost his job as

a Watchman

since,

immediately

after the case,

he became a

beerhouse keeper

at the fledgling

Beehive Inn

in

Huish.

Murder of Constable Penny

Just before midnight, during the evening of Saturday 18 January 1862, Police Constable William Hubbard of the Somerset Constabulary was on duty on Hendford Hill when, without warning, he was assaulted by a gang of navvies who had been employed on the railway. Hubbard then met Constable William Penny, and told him what had happened.

From the Police Gazette |

The rest of the navvies then gathered round and, being greatly outnumbered, Hubbard and Penny let the gang move on along Hendford Hill. The two Constables then met their Sergeant Keats and explained to him what had occurred. Together they returned to the gang of navvies, following them along the Dorchester Road, close to the Red House public house. A fight ensued and PC Penny was knocked to the ground, where the navvies viciously kicked him. |

Constable Penny was then taken into the Red House, where he was attended by doctors. William Penny never rallied properly and died the following Saturday. Three of the navvies were later tried for manslaughter; two were acquitted and the third received a sentence of four years.

Robert Slade Colmer

Sadly, space precludes an in-depth study of a man who was probably one of the worst Yeovilians of all time - Robert Slade Colmer. He was a herbalist and… a paedophile (he got off on that one), a back-street abortionist (actually a Middle Street abortionist), he was tried for manslaughter, made a bankrupt and he was an adulterer. Oh yes - he was also a murderer and the father of Ptolemy Colmer who, despite his father, became a physician, surgeon and Mayor of Yeovil .

On 9 December 1844 at Taunton winter assizes Robert, aged 27 was tried on the charge of "Carnally abusing a girl between the age of 11 and 12 years". For lack of evidence (and the court clearly didn’t believe the testimony of a child) he was found not guilty.

In October 1863, an inquest was opened before Dr Wybrants, at the Castle Inn, on the body of Elizabeth Fox, a young woman who had been living as a servant at Rimpton. It appeared that she was pregnant and that she went to Colmer for medical advice. She remained there some days, and death is said to have taken place early on Sunday morning. On post-mortem examination, a frightful laceration of the womb was found. After a lengthy inquest the jury bought in a verdict of manslaughter against Robert Slade Colmer. He was indicted for slaying Elizabeth Fox and was also indicted for misdemeanor or, in other words, concealment of birth. The evidence at Colmer's trial was all of a circumstantial nature and ultimately the jury returned a verdict of 'Not Guilty'.

In March 1880 Robert and his wife Jane, also a 'herbalist', were visited by a widow, Mary Budge of Crewkerne. Mary was pregnant by her young lodger and, in short, the Colmers performed an abortion after which Mary returned to Crewkerne on the train with her lover. She died in agony during that night. Robert and Jane Colmer were both tried at the Old Bailey, found guilty and convicted for the willful murder of Mary Budge at Yeovil, by illegal operation. (For full details of the trial, click here). On 3 August 1880 both Robert and Jane were sentenced to death. On 19 August 1880 the Home Office commuted the sentence of death on both Robert and Jane to one of penal servitude for life. In the 1881 census Robert Colmer, aged 66, was listed as a convicted felon in Pentonville prison, London. Jane was serving her sentence at Millbank prison, London.

Robert

Slade Colmer

died in prison

at the age of 73

in the winter of

1889. Jane,

however, was

somewhat luckier

than her husband

and was released

from prison. In

the 1891 census

she was 'living

on her own

means' in

Peter

Street with her

herbalist

daughter,

Cleopatra. Jane

died later that

year aged 76.